By Andrew Rapacke, Managing Partner, Registered Patent Attorney

A hardware startup launched its smart home device on Kickstarter in 2023, generating $500,000 in pre-orders within weeks. Three months later, they consulted a patent attorney about protecting their innovation. The news was devastating: their public campaign video had created prior art against their own invention, and a competitor had filed a provisional application two weeks after seeing the Kickstarter launch. Their delay cost them patent protection entirely.

This scenario plays out more often than you’d think. The distinction between an unpatentable idea and a patentable invention isn’t just legal theory; it determines who owns breakthrough technology and who loses millions in potential value.

Here’s what the law says: You cannot patent a mere idea. Not in the United States, not in Europe, not anywhere. The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office explicitly states that patent protection requires a concrete invention: a “new, nonobvious and useful” process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter. Abstract concepts, business notions, or the general ability to accomplish something never qualify, regardless of how revolutionary they seem. But here’s the opportunity: while ideas alone aren’t patentable, there are clear, proven pathways to transform your concept into something that does qualify for legal protection and generates real competitive advantage. At Rapacke Law Group, we specialize in helping tech innovators navigate exactly this transformation.

What you’ll learn:

- Why patent law draws a hard line between ideas and inventions, and what that means for you.

- The four specific requirements that make an invention patentable.

- How to move from concept to concrete, protectable innovation (with sector-specific examples).

- Protection strategies that work before you file, including when to use NDAs, confidentiality agreements, trade secrets, and provisional applications.

- Why 76% of self-filed patent applications get abandoned, and when professional help pays for itself.

Can Ideas Be Patented? – The hard line between ideas and inventions

Patent law protects concrete inventions: processes, machines, compositions of matter, manufactured articles, and specific improvements. Not aspirations. Not goals. Not the theoretical “ability to” accomplish something.

As of 2025, the USPTO continues to strictly exclude abstract ideas, natural phenomena, and laws of nature from patent eligibility. This practice follows landmark Supreme Court cases (Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank in 2014 and Mayo v. Prometheus in 2012), which established clear boundaries against patenting ideas dressed up as inventions.

Simply describing a desired result isn’t enough. You need to disclose a specific technical solution.

Consider these contrasts:

“Deliver groceries faster” is an unpatentable idea. A defined routing algorithm with specific data inputs, processing steps, and optimization parameters that reduces delivery times by 18% is a patentable invention. Companies like Uber have filed patents on concrete dispatch algorithms that use AI to predict demand and pre-position drivers. It’s the technical system that gets patented, not the goal of faster delivery.

“Use AI to detect fraud” is too abstract. A machine-learning pipeline with a specified neural network architecture, a defined training methodology, and quantified detection accuracy (e.g., 99.5% on a 2024 benchmark dataset) is patentable. The difference? One is an aspiration; the other is a detailed implementation with measurable results. For more on protecting AI innovations, see our AI Patent Mastery guide.

“Make electric cars more efficient” won’t earn you exclusive rights. A novel battery electrode composition with defined materials and manufacturing steps (for example, a new lithium-ion cathode formula that yields 15% longer cycle life) might qualify. Tesla holds patents on battery management systems and electrode formulations, not on the general concept of an efficient electric vehicle.

The rest of this article shows you exactly how to bridge the gap between having great ideas and developing patentable inventions that qualify for protection.

Why patent systems exclude ideas: the innovation economics

An “invention” in patent law isn’t something you imagine; it’s something you can build, use, or practice in the real world. It requires specificity: defined components, steps, materials, or configurations that someone skilled in the relevant field could replicate.

The U.S. Patent Act (35 U.S.C. § 101) and the European Patent Convention expressly exclude specific categories from patentability:

- Abstract ideas and mental processes.

- Mathematical formulas as such.

- Laws of nature and natural discoveries.

The rationale is straightforward: allowing anyone to monopolize foundational building blocks would stifle innovation rather than promote it.

Think about it this way: if someone could patent “online shopping,” every e-commerce business would owe them royalties. If Einstein had patented E = mc², nuclear physics research would have required his permission. Patent systems deliberately keep fundamental concepts in the public domain so all inventors can build upon them.

The European Patent Office frames this as requiring “technical character.” Solutions to purely business or administrative problems aren’t considered patentable inventions because they lack technical substance. “Super-sizing” a fast-food meal or offering a customer loyalty discount may be clever business moves, but they’re unpatentable under European law because they lack a technical effect.

Real examples across three sectors

Transportation technology: “Matching riders with drivers” cannot be patented; it’s a broad business method. A specific server-side dispatch algorithm that processes GPS coordinates, calculates optimal routing using defined parameters, and reduces average ride-hailing wait times from 8 minutes to 4 minutes (demonstrated in controlled 2024 urban trials) could qualify for protection. The latter has technical substance: an algorithmic technique with performance data that the mere idea lacks.

Healthcare innovations: A “diet plan for weight loss” is not patentable subject matter. A medical device with defined sensor arrays, signal-processing circuitry, and feedback mechanisms may be eligible for patent protection. So can a drug formulation with a specified molecular structure, dosage regimen, and clinical efficacy data. You can’t patent “lose weight by eating fewer carbs,” but you could patent a new low-carb food composition or an apparatus that monitors and affects metabolism in a novel way.

Educational technology: “Teach languages with AI” is too abstract. A detailed AI-based language tutoring system moves into patentable territory. For example: a speech recognition and feedback engine with a particular neural network architecture (defined layer by layer), a unique method of generating practice exercises, and evidence that it improved language proficiency scores by 23% over 2023 baselines. The concept (AI for teaching) stays public, but a concrete implementation (this specific AI system) is protectable.

Patent offices like the USPTO and EPO closely scrutinize applications for attempts to disguise abstract ideas as technical inventions. This is especially true in software, fintech, and business method filings, where examiners are trained to look past clever wording and ask: “Is there real technical innovation here, or is this just an idea implemented on a computer?”

As one USPTO guidance document puts it, at some level, “all inventions apply abstract ideas” or natural laws. Still, examiners must distinguish claims that recite an exception (which are ineligible) from those that integrate an idea into a practical application (which can be eligible).

Three types of patents—all require concrete implementations

You cannot patent an idea under any patent type. The type simply determines which aspect of a fully described concrete invention receives protection.

Utility patents are the most common type and protect new and useful processes, machines, manufactured articles, and compositions of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof. In the U.S., utility patents last 20 years from the earliest non-provisional filing date (maintenance fees required). A new field of battery chemistry introduced in 2025 would expire in 2045. Tesla’s numerous utility patents on charging technology and battery management systems exemplify this category.

Design patents protect the ornamental appearance of an article of manufacture: how something looks rather than how it works. They cover visual and surface design aspects, such as shape and decoration, rather than functional features. For applications filed on or after May 13, 2015, design patents last 15 years from grant with no maintenance fees. Apple’s design patents on the iPhone’s distinctive front face and rounded corners are well-known examples. A vague “style idea” won’t suffice; you need specific visual designs rendered in formal drawings.

Plant patents provide protection for new plant varieties that have been asexually reproduced. A plant patent protects the inventor’s right to exclude others from asexually reproducing, selling, or using the plant so protected. Unlike utility or design patents, plant patents specifically cover distinct and new plant varieties, such as cultivated sports, mutants, hybrids, and newly discovered seedlings, but not tuber-propagated plants or plants found in an uncultivated state. The process of filing a plant patent application involves submitting a detailed botanical description, evidence of asexual reproduction, and any necessary drawings. Plant patents differ from utility patents in that they do not protect methods or processes, but rather the plant itself.

Each patent type demands that you describe something specific and reproducible. Choosing the correct type is a strategic decision that often benefits from consulting patent professionals who can evaluate your invention’s unique characteristics.

The four requirements that separate ideas from inventions

Beyond being a concept, an invention must satisfy the core patentability requirements enforced by the USPTO, the EPO, and other patent offices worldwide.

1. Novelty

Your invention must be new. It cannot have been publicly disclosed anywhere in the world before your filing date. Patent examiners search “prior art” (existing patents, published papers, products, websites, etc.) to assess novelty.

This encompasses:

- Existing patents and published patent applications.

- Published academic papers.

- Public demonstrations and trade show displays.

- YouTube videos and social media posts.

- Any previous public use or sale.

If a substantially similar product was demonstrated at CES in January 2023, your patent application filed in March 2025 may lack novelty. A thorough patent search helps you verify that your invention truly breaks new ground.

Critical point: Even your own public disclosure counts against you. In the U.S., you have a one-year grace period for your own disclosures, but most countries have absolute novelty rules with no grace period at all. The hardware startup story that opened this article? That’s what happens when you disclose before filing.

2. Non-obviousness (Inventive Step)

Even if your invention is new, it must also be a non-obvious improvement over existing knowledge. This means it wouldn’t be obvious to a hypothetical “person of ordinary skill in the art” (POSITA) who is aware of all relevant prior art.

If your “innovation” is merely using aluminum instead of steel in a known device, with no unexpected benefits, an examiner will likely say it’s obvious. You can’t simply substitute known materials or combine familiar techniques unless something unexpected results.

The legal test involves Graham factors:

- The scope of prior art.

- The differences between your invention and prior art.

- Secondary considerations (Does it solve a long-felt need? Has it achieved commercial success that suggests it wasn’t obvious?).

Example: If your AI-based image compression method combines attention mechanisms with traditional compression in a novel way, producing a 35% file size reduction at equal quality, and experts hadn’t achieved this level before, you can argue non-obviousness. The quantitative gains support an inventive step.

3. Utility

The invention must be applicable; it must have a specific, substantial, and credible use. In the U.S., this is generally a low bar (almost anything with a real-world application meets it), but it does exclude perpetual motion machines and purely theoretical constructs.

Your patent doesn’t have to prove the invention works (you can usually assume utility if it’s plausible). Still, if an invention appears to violate known scientific laws, the USPTO will ask for evidence of operability.

4. Enablement and Written Description

These relate to how you disclose the invention in the patent application (per 35 U.S.C. § 112 in the U.S. and similar rules elsewhere).

Enablement means your specification must teach a person skilled in the field how to make and use the invention without undue experimentation.

Written description means you must fully describe the invention, demonstrating that you possessed it as of the filing date.

Together, these requirements guard against purely speculative patents. You can’t patent a drug by saying ‘a compound that cures cancer’ without specifying the compound or how to make it; that would be an idea, not an enabled invention.

Case study: AI-based image compression

Let’s tie all four requirements together with a concrete example from 2024:

Novelty: You perform a literature and patent search and confirm that no one has published or patented this exact approach. It uses a particular transformer neural network architecture that has not previously been applied to image compression. It’s new.

Non-obviousness: Simply using AI for compression might be obvious, but your approach combines attention mechanisms with traditional compression in a non-trivial way, resulting in a 35% smaller file size at the same image quality as standard methods. This represents an unexpected improvement. During patent prosecution, you might show: “Our method achieved 0.95 SSIM image quality at 0.5 bits/pixel, whereas the best prior art achieved 0.92 SSIM at 0.5 bpp.” Those quantitative gains support an inventive step.

Utility: The method clearly has real-world use. Image and video providers always need better compression. It’s a functioning software tool, not a perpetual motion machine.

Enablement: In your patent application, you include an architecture diagram of your transformer network, hyperparameter details, pseudocode, or descriptions of your training data. You might include actual code lines or detailed mathematical formulas. You describe the results of a working prototype on standard image datasets. This thorough disclosure enables others to follow your footsteps once the patent expires. It also proves you actually possessed the invention in 2024, not just an idea like ‘maybe use a neural net for compression’.

This invention, properly drafted, could meet all four criteria. By contrast, a vague idea to “use AI to compress images better” with no specifics would meet none of them.

Abstract ideas vs. concrete applications: the Alice/Mayo framework

Many inventors struggle with the “abstract idea” rule, especially in software, fintech, and online services. Understanding how to reframe concepts into patent-eligible applications often separates granted patents from rejected ones. For SaaS founders navigating these challenges, our SaaS Patent Guide 2.0 provides detailed strategies for protecting software innovations.

Three critical examples

“Secure online payments” is too abstract. It’s a goal. But suppose you invent a specific cryptographic protocol: a defined method for exchanging encrypted tokens using quantum-resistant algorithms, with detailed message flow, key-exchange techniques, and measured performance improvements (reducing transaction latency from 2.3 seconds to 0.8 seconds in tests). This is now a concrete application: a step-by-step protocol solving a technical problem (speed/security trade-off) in online transactions, not just ‘do it with AI or blockchain’.

The concept of “Personalized advertising” belongs in the public domain. A defined wearable health-monitoring system: that’s an invention. For example, imagine you created a wrist-worn device with a specific arrangement of sensors (say, 3-lead ECG electrodes in a new configuration), running a particular signal-processing algorithm that filters noise in a novel manner, and able to detect atrial fibrillation with 94.7% sensitivity in clinical trials. The focus is on how personalization is technically achieved, not just the idea of doing it.

“Monitor health with wearables” is too broad. A defined wearable health-monitoring system (say, a wrist-worn device with a specific arrangement of sensors like 3-lead ECG electrodes in a new configuration), running a particular signal-processing algorithm that filters noise in a novel manner, able to detect atrial fibrillation with 94.7% sensitivity in clinical trials: that’s an invention. You’d claim the concrete combination of hardware and algorithms. The general idea of health monitoring is unpatentable, but this device with these features is protectable.

The two-step test in U.S. patent law

Patent examiners apply the Alice/Mayo test for abstract ideas:

Step 1: Determine if the claim is directed to a ‘judicial exception,’ meaning an abstract idea, law of nature, or natural phenomenon. Abstract ideas include algorithms, mathematical formulas, fundamental economic practices, methods of organizing human activity, and mental processes when taken on their own.

Step 2: If the claim is directed to an abstract idea, determine whether it adds ‘significantly more.’ This means an inventive concept that transforms the idea into a patent-eligible application. This means looking beyond the abstract idea: do they amount to more than well-understood, routine, conventional activities?

Taking an abstract idea and saying “do it on a generic computer” doesn’t count as significantly more. But improving the computer’s functionality or achieving a technical outcome in a novel way can qualify as considerably more and make the claim eligible.

The European approach: technical character

The European Patent Office uses a different framework, focusing on whether an invention has “technical character” and provides a technical solution to a technical problem. The EPO ignores purely non-technical features (like business or game rules) when assessing inventive step.

Pure business methods or mathematical methods “as such” are not patentable in Europe, but if you embed them in a technological context (a control system for an engine, a cryptographic communication method, etc.), they can be.

The practical takeaway

Frame your invention as a specific technological solution. If you find yourself describing it as “the idea of doing X for [business goal],” step back and ask: How am I actually implementing it? What components, what steps, what measurable performance do I have?

Often, this means working with patent professionals who know how to draft claims focusing on technical improvements, such as ‘reduces database query time by 50% via a new indexing technique’ rather than ‘makes e-commerce more efficient.’

From idea to invention: six practical steps

The key task for any inventor is to transform a new idea into a documented, workable solution that meets patentability criteria. This development process requires deliberate effort, but the steps are straightforward.

1. Clarify the problem and solution

Write down precisely what technical problem you’re solving and how you propose to solve it. This sounds simple, but many inventors skip this critical step.

For example, if you’re addressing warehouse picking delays in 2025 logistics operations, don’t write “I have an idea to make it faster.” Specify the bottleneck: “In current warehouse systems, pickers spend 47 seconds per pick on average, largely due to inefficient routing.” Then specify your solution: “My system uses coordinated robots with sensor fusion (LIDAR + camera) to navigate and hand off items, reducing average pick time to 22 seconds.”

Now you have concrete elements: robots, sensors, an algorithm, and a target metric. This clarity not only helps make your idea patentable, it guides your development.

2. Prototype or model your invention

Build a basic prototype, run simulations, or create detailed process descriptions. While a physical prototype isn’t legally required for filing, developing technical details is essential.

A working model (even a rough one) helps you understand what actually makes your invention work and what aspects are novel. Writing sample code for your software idea might expose edge cases you need to handle. Building part of a machine might reveal a needed design tweak.

Some inventors also perform experiments or collect data at this stage, which can later strengthen the patent by providing evidence of unexpected results or advantages.

3. Document everything

Maintain a dated engineering notebook or digital log. Record how you got the idea, sketches of design iterations, test results from prototypes, etc.

In the U.S., since the 2013 America Invents Act, it’s a first-to-file system (whoever files first has priority), but documenting your work still has benefits. It can help prove derivation (if someone stole your idea) or show the development timeline.

Use bound notebooks or secure digital logs. Include photos, diagrams, and flowcharts, and annotate them. If you work in a team, have co-inventors sign and date entries. This record can be a supporting exhibit in patent prosecution or litigation.

4. Keep it confidential

Until you have a patent application filed (even a provisional), treat your invention details as trade secret information. This means:

- Limit who you share it with.

- Use a confidentiality agreement (NDAs) when you must disclose.

- Avoid any public disclosure: don’t post online, don’t publish papers, don’t display publicly,

In most countries, any public disclosure before filing will destroy novelty and bar you from getting a patent. The U.S. has a limited one-year grace period for your own disclosures, but relying on it is risky and doesn’t protect you internationally.

5. Research prior art

Before investing significantly in patent filing, do homework on what exists. Use:

- Google Patents.

- USPTO/EPO databases.

- WIPO’s PATENTSCOPE.

- Academic publications (Google Scholar, IEEE Xplore, etc.).

Look for concepts similar to yours. You’ll likely find something close; don’t be disheartened. The goal is understanding the landscape: what problems have others solved, and how is your approach different?

You might discover someone in 2018 had a similar idea, but it failed in some aspect, which your invention improves. That’s great to highlight later.

Document the closest prior art you find. When you talk to a patent attorney, providing prior art helps them craft stronger claims and anticipate examiner rejections.

6. Decide your patent strategy

Key considerations include:

Timing: File before you disclose or launch the product. But don’t file too early with half-baked details, as what you file is locked in. Often, inventors file a provisional patent application as soon as they have a solid concept, then continue R&D for up to 12 months before filing the full non-provisional patent application.

Provisional applications: A provisional filing in the U.S. is relatively low-cost and not examined. It’s a placeholder that secures a filing date (and you can legally label the invention ‘patent pending’). It buys you 12 months to file a complete application.

International protection: Patents are territorial. A U.S. patent only protects in the U.S. If you need worldwide protection, you have to file in each target country (or use the Patent Cooperation Treaty to streamline international applications).

Budget: The costs of obtaining a patent can range from a few thousand to over $20,000, depending on the complexity and attorney fees. Decide what investment makes sense given the invention’s potential.

Protecting your idea before filing

There’s often a vulnerable period when you have only an idea or an early prototype and no patent filing yet. During these early stages of development, alternative protection strategies matter.

Non-disclosure agreements (NDAs)

An NDA creates contractual confidentiality obligations between you and anyone you share information with. If you need to discuss your idea with a manufacturer, developer, or potential co-founder, it’s prudent to get them to sign an NDA first. It legally binds them to keep your secrets.

Limits of NDAs:

- They only bind parties who sign them.

- If someone independently comes up with the idea or learns of it elsewhere, your NDA with a particular party won’t prevent them from doing so.

- Some entities (e.g., confident investors or companies) might refuse to sign NDAs as a matter of policy.

Still, NDAs are standard practice and signal that you take IP seriously.

Trade secrets

While you’re developing an invention (and even after, if you choose not to patent it), you can rely on trade secret protection. A trade secret is information that has economic value from not being generally known, which you take reasonable steps to keep secret.

Classic examples include: formulas, recipes, algorithms, business processes, and customer lists. The Coca-Cola formula has been kept as a trade secret for over 130 years rather than patented.

Benefits: Can last indefinitely (as long as you maintain secrecy). No registration cost, no expiration.

Downsides: If someone else lawfully discovers the secret (through reverse engineering or their own R&D), you have no protection. With a patent, even if they reverse engineer your product, they can’t legally exploit it during the patent term.

For early-stage ideas, treating them as trade secrets is natural. You haven’t disclosed them, and you’re actively keeping them under wraps.

Provisional patent applications

A provisional patent application is a temporary, internal-only filing with the USPTO that establishes an official priority date for your invention. It is never examined or published (unless later referenced in a published full application).

Think of it as planting a flag: “As of today, I claim this invention.”

Benefits:

- File it with whatever materials you have; formal patent claims aren’t required.

- Much lower cost (often $150-300 filing fee for small entities).

- Gives you time to refine the invention and write a polished non-provisional patent application.

- Allows you to mark products “patent pending.”

Many entrepreneurs file a provisional right before a public reveal. If you want to exhibit at a trade show or launch a crowdfunding campaign, filing a provisional the day before means you can go public safely.

Critical warning: Public disclosure before filing can be fatal to your patent rights. If you reveal your invention to the public (in writing, verbally in a public setting, online, etc.) before having at least a provisional filed, you risk losing foreign patent rights immediately and start the U.S. one-year clock ticking.

Many countries have absolute novelty rules with no grace period. Once information is in the wild, even if you later file a patent, that earlier info becomes prior art that can be cited against you.

Real-world examples across four sectors

Walking through sector-specific examples helps solidify the distinction between unpatentable concepts and potentially patentable inventions.

Transportation and logistics

Idea (not patentable): “Self-driving deliveries”: a goal shared by dozens of companies.

Invention (potentially patentable): A specific control system for coordinating autonomous delivery robots in a warehouse, with defined sensor fusion algorithms integrating LIDAR and camera data, collision-avoidance logic using specified safety margins, and navigation protocols tested in 2024 trials, achieving 99.2% successful delivery rates. This represents a concrete technical implementation.

Software and communication

Idea (not patentable): “Instant global messaging”: a feature users want.

Invention (potentially patentable): A particular compression and routing technique using specified packet formatting, priority queuing algorithms, and edge server deployment patterns, reducing average message latency from 120 milliseconds to 70 milliseconds under 2025 5G network conditions. The technical solution, not the user benefit, is what the patent protects.

Medical and biotech

Idea (not patentable): “Cure Alzheimer’s disease”: an aspiration millions share.

Invention (potentially patentable): A defined small molecule with a specific chemical structure (identified by molecular formula and stereochemistry), a dosage regimen specifying 50mg twice daily for 24 weeks, and Phase I clinical data demonstrating specific biomarker improvements. The claimed subject matter is the particular compound and its use, not the goal of curing a disease.

Clean energy

Idea (not patentable): “Store solar energy cheaply”: a problem statement, not a solution.

Invention (potentially patentable): A detailed battery electrode composition specifying exact material ratios (e.g., 73% lithium iron phosphate, 15% conductive carbon, 12% polymer binder), manufacturing methods including coating thickness and curing temperatures, and measured performance showing 15% improved cycle life over 2022 commercial baselines.

In each example, the distinction is clear: broad goals and abstract ideas remain in the public domain, while concrete techniques, devices, and compositions that solve technical problems can receive patent protection.

Why the idea/invention line matters: global economics

Modern innovation economies depend heavily on patents, but only when they protect fundamental inventions rather than vague ideas. This distinction shapes how billions of dollars flow through technology sectors worldwide.

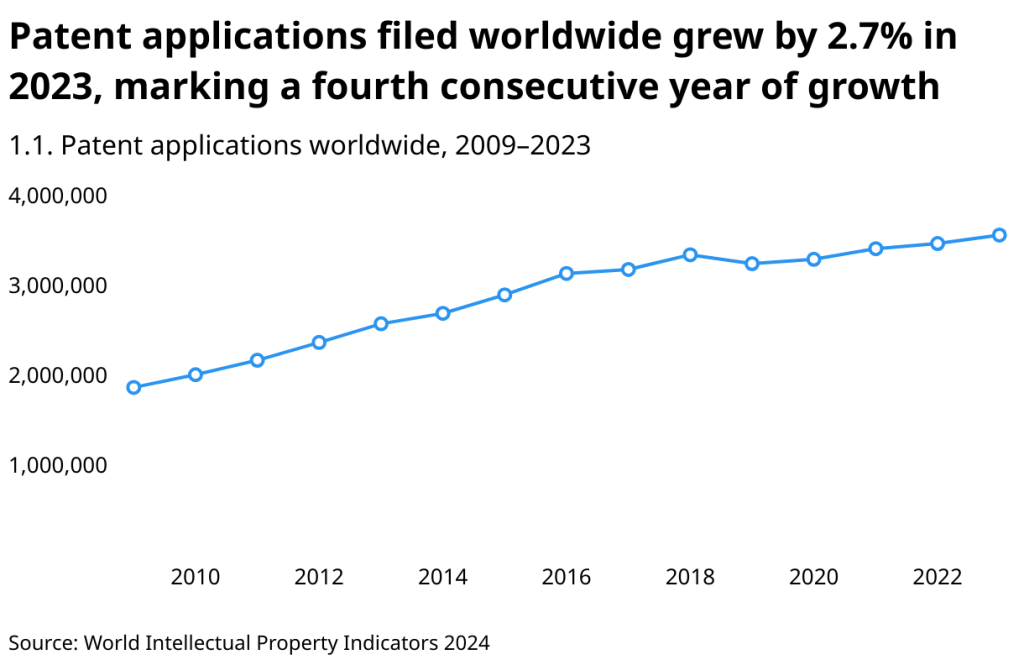

Patent activity has been booming. In 2023, innovators filed 3.55 million applications globally, a record high.

Figure 1: Global Patent Filings Continue to Reach Record Levels: Worldwide patent application filings increased to approximately 3.55 million in 2023, marking the highest level on record and extending a multi-year growth trend that underscores the rising economic importance of technological innovation and patent protection. Source: World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), World Intellectual Property Indicators 2024

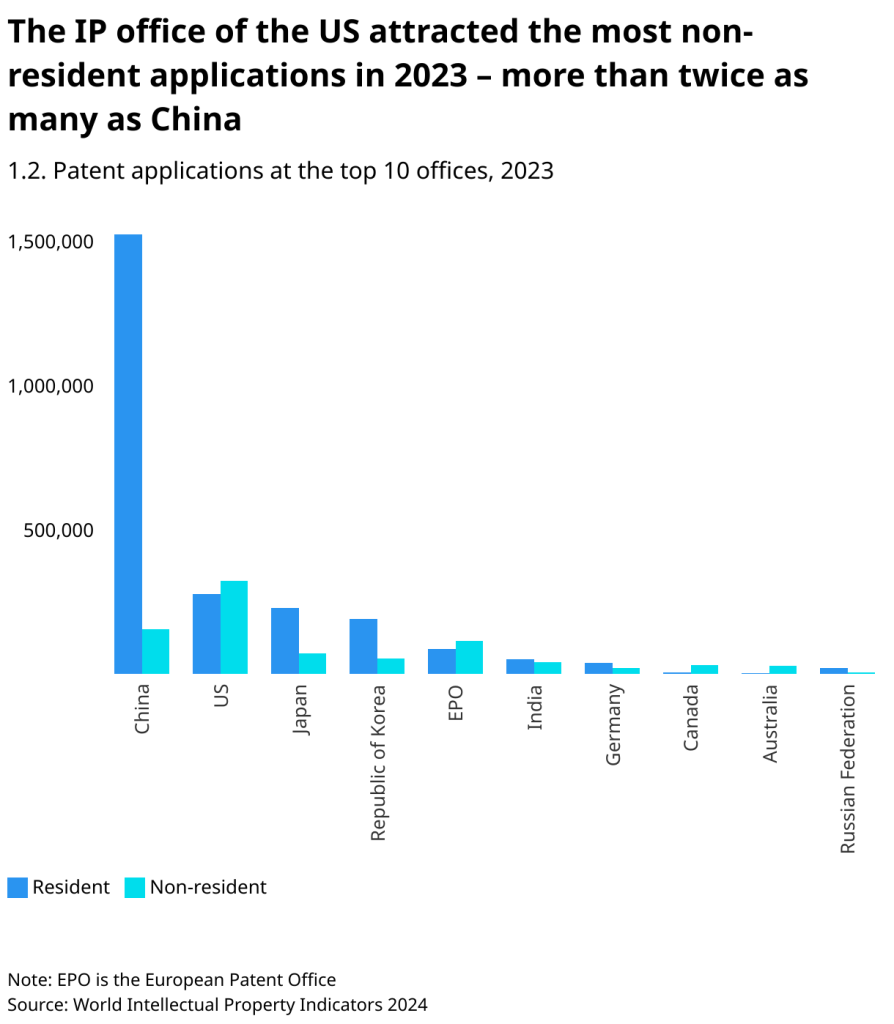

According to WIPO data, patent activity reached record levels in 2023:

- China filed approximately 1.64 million patent applications.

- The United States filed around 518,000 applications.

- Japan filed 414,000 applications.

- South Korea filed 288,000 applications.

- Germany filed 133,000 applications.

Asian patent offices received 68.7% of all global patent applications in 2023 (nearly two-thirds of worldwide filings), reflecting the shift in innovation leadership toward Asia over the past few decades.

Figure 3: Asia’s Share of Global Patent Filings Has Expanded Rapidly: Between 2013 and 2023, Asia’s share of global patent applications grew from about 58% to nearly 69%, while North America and Europe experienced declining shares, highlighting a significant shift in where patent-driven innovation activity is concentrated worldwide. Source: World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), World Intellectual Property Indicators 2024

The value of intellectual property

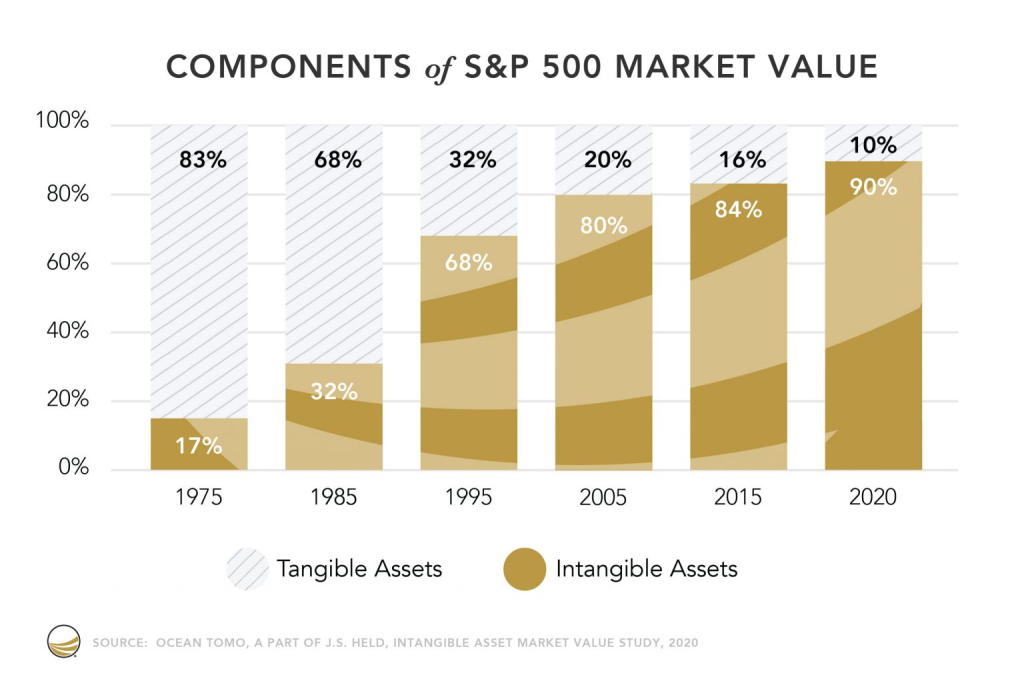

Various studies estimate that intangible assets, including patents, trade secrets, and other intellectual property, now account for 80-90% of the market value of large, publicly traded companies. In 1975, that figure was only around 17%. The rise of the tech and knowledge industries means that protecting ideas (in the form of inventions) is crucial for businesses.

Figure 3: Intangible Assets Now Dominate Corporate Value: Intangible assets—including patents, trade secrets, software, and brand equity—have grown from roughly 17% of S&P 500 market value in 1975 to approximately 90% by 2020, reflecting the central role of intellectual property in modern innovation-driven economies. Source: Ocean Tomo Intangible Asset Market Value Study (2020)

While only about 9% of European SMEs have registered any intellectual property rights, those that do tend to outperform their peers. An EPO study found that SMEs with at least one patent or other IP right were:

- 21% more likely to experience growth in subsequent years.

- 10% more likely to become high-growth firms.

The startup advantage

For startups, patents can be a make-or-break factor in attracting investment. A Harvard-NYU-Stanford study showed that winning a first patent increases a startup’s chances of:

- Securing venture capital funding by about 47% within three years.

- Securing loans by 76%.

- Achieving a successful exit (IPO or acquisition) more than doubles.

Why? A patent on a real, working invention gives investors confidence. It’s a sign the company has something unique and defensible, not just an idea anyone could copy.

Why ideas can’t be patented: preventing monopolies

Consider whether the patent system allowed protection of broad ideas. If someone could patent “online shopping” in the 1990s, or “social networking” in the 2000s, or “machine learning on medical data” in the 2010s, imagine the bottleneck.

A single patent holder could block all others from developing any implementation of those ideas, even if the others came up with better methods. That would concentrate too much power, discourage research, and ultimately slow technological progress.

By restricting patents to specific implementations, the law forces inventors to keep innovating. You can’t sit back on a broad idea patent; you only get a reward for particular solutions you develop, and others are free to create different solutions.

The groundbreaking mRNA vaccine technology that proved crucial during COVID-19 was based on decades of open research in molecular biology (no one owns the idea of using mRNA in therapy). Still, companies like BioNTech and Moderna held patents on specific lipid nanoparticle formulations and modified mRNA sequences that enabled the vaccines. Those specific inventions were worth billions and saved millions of lives. The general idea was free, but only those who nailed down working solutions got patents.

Working with patent professionals: when DIY isn’t worth it

While individuals can file applications on their own, navigating the fine line between unpatentable ideas and patentable inventions is where patent attorneys and patent agents provide immense value. A patent lawyer can help prepare documents, ensure compliance with patent office requirements, and protect your intellectual property rights throughout the patent process.

The data on DIY patent filings is stark: Studies have found that roughly 76% of self-filed (pro se) patent applications are abandoned without issuance, compared to about 35% for those filed with professional representation.

That gap is enormous, underscoring the complexity of patent drafting and prosecution. The USPTO itself cautions that pro se applicants likely face “considerable difficulty” and risk inadequate protection unless they are very familiar with patent law.

What patent professionals do

Prior art search & patentability opinion: A patent attorney can conduct a thorough prior art search using specialized databases and expertise in reading patent language. They can provide a patentability opinion letter: an analysis of whether your invention is likely to be considered novel and non-obvious over the prior art. This can save you time and money by focusing on truly inventive parts.

Reframing the invention: Perhaps the most critical skill is the ability to take your concept and frame it in legal/technical terms that patent law recognizes as patentable. Inventors naturally talk in terms of ideas and goals; patent attorneys translate that into specific embodiments and claims.

For example, you might say, “I have an idea for software that automatically does X.” A reasonable patent attorney will dig deeper: How specifically? What are the steps? What’s the architecture? What does it improve? They might realize the novelty isn’t in the overall software concept, but in a particular algorithm you devised. They’ll then draft claims focused on that algorithm’s unique features.

Quality of the application: Writing a patent application is an art. There are formal sections (Background, Summary, Detailed Description, Claims, etc.), each with a purpose. Professionals know how to write the Detailed Description to cover various permutations of your invention without being so vague as to lack support. They understand the legal meanings of words in claims and try to preempt objections.

Prosecution & office actions: After you file a patent, typically an examiner comes back with an Office Action, a document saying ‘Claim 1 is rejected because of X prior art or because it’s deemed indefinite, etc.’ Patent professionals know how to argue against rejections on legal and factual grounds, handle procedural requirements, and navigate the back-and-forth with examiners.

Strategic advisory: Beyond the mechanics of one patent, a good IP professional helps craft your broader strategy. Should you file patents or keep some things as trade secrets? Should you pursue international patents, or is the U.S. enough? Is this invention likely to hold commercial value, or is it more defensive?

The RLG advantage for tech innovators

At Rapacke Law Group, we specialize in tech IP, particularly AI patents and SaaS innovations. Unlike traditional hourly-billing firms, we offer transparent fixed-fee pricing so you know precisely what patent protection costs upfront. No surprises, no scope creep, no meter running.

Our provisional patent package includes:

- FREE strategy call with our patent team.

- Experienced US patent attorneys lead your application from start to finish.

- One transparent flat fee covering the entire provisional patent application process.

- Full refund if USPTO denies your provisional patent application*.

- Full refund or additional searches if your application has patentability issues (your choice)*.

When to get help

At a minimum, schedule a free consultation with a patent professional early. They can give you a sense of the road ahead.

If you’re serious about turning your idea into a business or licensing it, professional guidance is often invaluable. Remember those statistics: even the USPTO warns that unless you’re deeply familiar with patent law, you’ll likely face considerable difficulty going it alone and risk inadequate protection.

According to various studies, about 94% of patent applications from small entities are filed with an attorney or agent; you’ll be in good company if you use professional help.

Your Next Steps to Patent Protection Success

You’ve learned the fundamental distinction between ideas and inventions, and why that line matters for protecting your innovation. The question now isn’t whether ideas are patentable (they’re not), but whether you’ll take the steps to transform your concept into a concrete, protectable invention.

The bottom line: A weak patent application (one that tries to claim broad ideas rather than specific implementations) helps your competitors by showing them what doesn’t work while giving you zero protection. A well-drafted patent grounded in concrete technical details deters competitors, attracts investors, and creates real market value.

Time is working against you. Every day you wait to file is another day a competitor could beat you to the patent office under the first-to-file system. Every conversation about your invention without an NDA in place risks creating prior art that blocks your own patent. Every product demonstration or crowdfunding campaign launched before filing could cost you foreign patent rights entirely, and potentially U.S. rights too.

The difference between patent success and failure often comes down to three factors: timing your disclosure correctly, documenting your invention thoroughly, and working with attorneys who understand how to translate technical innovations into legally defensible claims.

- Schedule a Free IP Strategy Call with our patent team to evaluate your invention’s patentability and develop a strategic protection plan tailored to your innovation.

- Document your invention systematically using the six-step framework outlined above. Clarity about your technical solution is the foundation of every strong patent.

- File a provisional patent application if you need to disclose your invention soon. This establishes your priority date and gives you 12 months to refine your strategy.

- Research the competitive landscape by conducting thorough prior art searches to understand what’s already patented and identify your true innovation.

- Keep your invention confidential until you have at least provisional protection in place. One premature disclosure can destroy years of R&D investment.

Your invention deserves protection that matches its potential. The patent system rewards those who invest the effort to move beyond abstract ideas to concrete technical solutions. Whether you’re developing AI algorithms, hardware innovations, software platforms, or emerging technologies, the right patent strategy transforms defensive legal paperwork into an offensive competitive advantage.

Proper patent preparation isn’t an expense; it’s an investment in exclusivity, investor confidence, and market position. The startups that secure strong patents early don’t just protect their innovations; they build moats that let them scale without worrying about competitors copying their breakthroughs.

Don’t let your innovation remain just an idea. Turn it into an invention, and turn that invention into intellectual property that drives your business forward.

To Your Success,

Andrew Rapacke

Managing Partner, Registered Patent Attorney

Rapacke Law Group

Connect with us: LinkedIn | Twitter/X | Instagram

*Terms and conditions apply. Contact RLG for full guarantee details.