By Andrew Rapacke, Managing Partner & Registered Patent Attorney

The race to secure patent rights in the U.S. has never been more competitive. Every year, more inventors, startups, and R&D teams enter the system—driving longer wait times, higher filing volumes, and increased pressure to get your application right the first time. Whether you’ve developed a groundbreaking AI algorithm, designed a SaaS platform, or created a new manufacturing process, understanding how to patent my product is no longer optional—it’s essential to protecting your innovation before competitors move in.

In Fiscal Year 2023, the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) received nearly 594,000 new utility patent applications and about 53,665 design patent filings, according to USPTO data. This marks a fourth consecutive year of global growth, with worldwide patent filings up 2.7% in 2023. As more innovators pursue protection, examiners face record workloads and applicants face greater scrutiny over novelty, non-obviousness, and claim precision.

The result: securing a patent now demands both strategic foresight and procedural accuracy.

This detailed guide removes uncertainty and positions you for patent success. You’ll learn the exact documentation required, realistic timelines based on current USPTO data, and strategic decisions that increase your odds of approval—especially since 76% of self-filed (pro se) applications are abandoned, compared to just 35% when handled by registered professionals. You’ll also see how working with a specialized patent firm like Rapacke Law Group, with its fixed-fee pricing and deep expertise in tech and software IP, can be the difference between a patent that truly protects your innovation and one that gives competitors a roadmap to beat you.

Patent Application Quick Start Guide

Before diving into detailed steps, here’s your essential roadmap for patenting your product:

The 5 Essential Steps:

- Determine Patentability – Verify your product is new, useful, and non-obvious. If it fails these basic criteria under U.S. law, it cannot be patented.

- Conduct a Patent Search – Research existing patents and publications (prior art) to confirm your invention’s novelty.

- Choose Application Type – Select the appropriate path: utility patent vs. design patent, and provisional vs. nonprovisional application.

- File with the USPTO – Submit your patent application through the USPTO’s electronic filing system (Patent Center) (uspto’s electronic filing system) with all required documents and fees.

- Respond to Examiner Feedback – Address any Office Actions or rejections from the patent examiner until your application is allowed or finally rejected.

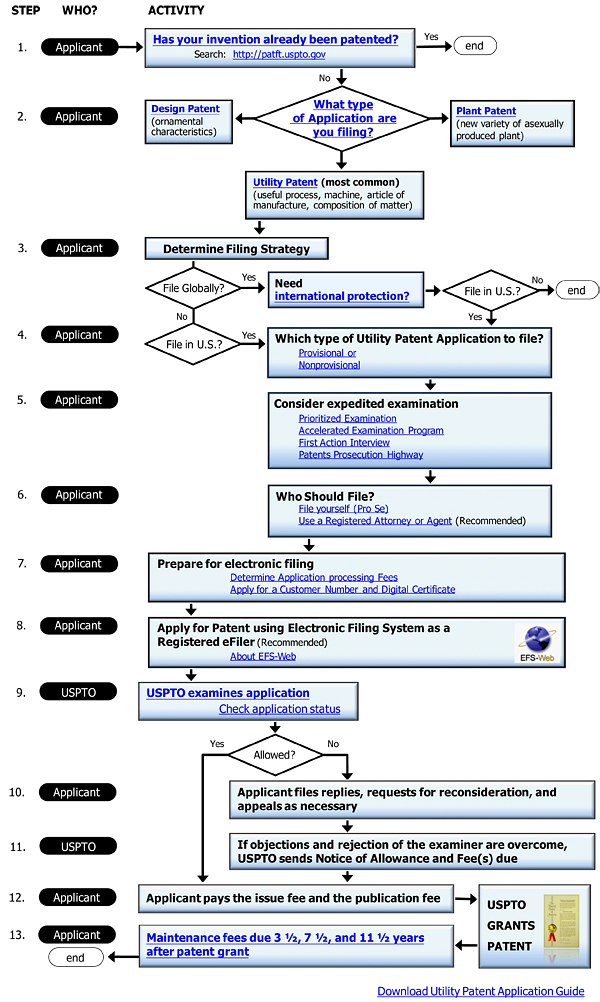

The following flowchart provides a high-level roadmap of the U.S. utility patent process — from your initial invention disclosure through examination, responses to Office Actions, and eventual allowance or final decision.

Timeline Expectations: The average time to a first Office Action was about 20.2 months as of April 2024, reflecting a large backlog of applications. The utility patent examination process typically takes about 2 to 3 years (often 22 to 30 months) from filing to final disposition. In more complex cases involving RCEs or multiple claim amendments, total pendency can extend toward 3 to 4 years or more. Design patents have traditionally been faster, but with the surging popularity of design filings, the average pendency has stretched to around 22 months in recent years.

As of FY2024, the backlog of unexamined patent applications climbed to over 740,000 (for utility/plant/reissue), a level not seen since the mid-2000s. This means patience and planning are essential—your application will spend considerable time in the queue before examination begins.

Key Requirements: Your product must satisfy three fundamental criteria to be patentable:

- Novelty: The invention must be genuinely new—not previously disclosed in any public forum or publication worldwide. Even your own public disclosure (like a trade show demo or crowdfunding page) before filing can destroy novelty.

- Utility: The invention must have a specific, substantial, and credible use. This requirement is usually easy to meet for physical products or processes.

- Non-Obviousness: This is often the most challenging hurdle. The invention cannot be obvious to a person having ordinary skill in the relevant field.

Filing Costs Overview: Basic USPTO fees for a utility patent application (as of 2024):

| Entity Type | Basic Filing Fee | Search Fee | Examination Fee | Total (min.) |

| Micro Entity (80% discount) | $320 | $160 | $160 | $640 |

| Small Entity (60% discount) | $800 | $400 | $400 | $1,600 |

| Large Entity (full fee) | $1,600 | $800 | $800 | $3,200 |

These USPTO fees are just the beginning—you’ll also pay an issue fee upon allowance and periodic maintenance fees to keep a utility patent active (at 3.5, 7.5, and 11.5 years after grant). As of the Jan 19, 2025, schedule, a small entity pays $860, $1,616, and $3,312, respectively, at those intervals; large entities pay $2,150, $4,040, and $8,280.

A publication fee is also required for most non-provisional applications and should be factored into the total cost of obtaining a patent.

A fee increase of roughly 10% on front-end fees takes effect in 2025 to account for inflation and bolster the USPTO’s operating reserves. Always check the latest USPTO fee schedule before filing.

Determine If Your Product Can Be Patented

Not every invention qualifies for patent protection. The USPTO applies strict criteria to determine patentability, and understanding these requirements upfront can save you significant time and money by filtering out non-viable ideas early.

The Three Patentability Requirements:

1. Novelty (35 U.S.C. § 102): Your invention must be genuinely new. This means it has never been publicly disclosed or described in the prior art before your effective filing date. Prior art encompasses any public patents, patent applications, journal articles, books, websites, products on sale, etc., worldwide.

The U.S. allows a one-year grace period for an inventor’s own disclosures, but many foreign countries do not. To illustrate, if you published a paper or showed a prototype of your invention last year, you must generally file a patent application within one year of that disclosure in the U.S., and ideally before any disclosure to preserve rights internationally.

2. Utility (35 U.S.C. § 101): The invention must have some specific and valuable purpose. This is usually straightforward for gadgets, machines, compositions, and processes. The bar for utility is low, but it must be credible. If you claim something that violates known science (like a perpetual motion device or purely abstract idea), the USPTO may reject it for lack of usefulness or operability.

3. Non-Obviousness (35 U.S.C. § 103): Your invention must not be a noticeable variation of existing knowledge. Examiners will combine references and use their technical judgment to argue that a person of ordinary skill could have arrived at your invention easily. To overcome this, your invention should include some unexpected feature or result. For example, simply substituting one material for another in a known device might be deemed obvious unless it yields surprising benefits.

What Cannot Be Patented:

U.S. law and court decisions exclude specific categories from patent eligibility:

- Abstract ideas, mathematical formulas, and purely mental processes – Software-related inventions must be tied to a technical solution to avoid being considered abstract. This is particularly critical for SaaS and AI innovations, where the key is demonstrating how your algorithm solves a concrete technical problem rather than just automating a business process.

- Natural phenomena and laws of nature – You can’t patent something that exists in nature (like a naturally occurring gene or mineral) or basic principles like E=mc².

- Business methods and financial schemes – These are only patentable in minimal cases after the Supreme Court’s Alice decision.

- Artistic creations – Like paintings, music, or literature. These may fall under copyright, not patent.

- Methods of medical treatment on humans – In some cases, these are allowed in the U.S., but in other countries, they are disallowed. Diagnostic procedures and surgical techniques may also face patentability issues under U.S. law, based on recent case law.

- Inventions useful solely in atomic weapons – By law (42 U.S.C. § 2181), particular nuclear material inventions are barred from patents for national security reasons.

Examples of Patentable Products:

- AI and Machine Learning Technologies: Neural network architectures for natural language processing, computer vision systems that improve object detection accuracy, or AI-powered recommendation engines that optimize user engagement through novel technical approaches. These AI innovations face unique §101 eligibility challenges post-Alice. At Rapacke Law Group, our specialized expertise in AI patents enables us to strategically frame your claims to overcome these hurdles—our track record shows consistent success where many practitioners struggle with abstract idea rejections.

- SaaS Platform Innovations: Cloud-based data synchronization methods, novel API architectures that improve system performance, or distributed computing systems that solve technical scalability challenges.

- Smartphone technologies: Apple has utility patents on multitouch interfaces and design patents on the iPhone’s ornamental shape and icon layout.

- Software-implemented inventions: A machine learning algorithm for image recognition that provides a technical improvement (software is patentable if it offers a concrete technical solution, not just an abstract idea).

- New manufacturing processes: A novel method for producing carbon fiber that yields improved strength.

- Use of new materials in product design: Experimenting with innovative materials to enhance product functionality, sensitivity, durability, or appearance, which can also support patent protection strategies by providing unique features or unexpected results.

For more detailed guidance on patenting AI innovations, download our comprehensive AI Patent Mastery resource, which includes strategies we’ve refined through hundreds of successful AI patent applications. For SaaS-specific strategy, see our SaaS Patent Guide 2.0.

Self-Assessment Checklist:

□ Is it truly novel? Search your own knowledge and the internet. If you can find your invention (or something very similar) already out there, you likely cannot patent it.

□ Is it non-obvious? Does your product combine existing elements uncommonly or achieve an unexpected result? Would a professional in the field be surprised by the approach or outcome?

□ Does it have a clear use? Can you explain what your invention does and why someone would want it? (If you can’t articulate a use, it may fail the utility requirement.)

□ Have you refrained from public disclosure? Ideally, you have not published or sold the invention yet. If you did, ensure it was within the last 12 months (for the U.S. grace period), and be aware that you may have forfeited rights in other countries.

□ Does it fall into a patent-eligible category? (Process, machine, article of manufacture, composition of matter, or an improvement of any of these.) If it’s just a scheme, an artistic work, or a naturally occurring thing, it’s not patentable.

□ Do you plan to refine the invention? If your concept isn’t fully baked or you anticipate changes, consider starting with a provisional application (more on that later).

If you answered “no” to any of these questions, you may need to refine your invention or reconsider whether patent protection is appropriate. It’s better to address issues of novelty or obviousness early than to invest in a full application only to have it rejected.

Conduct a Comprehensive Patent Search

A thorough patent search is one of the most critical steps in the patent application process. By researching existing patents and published applications, you can gauge whether your invention is truly new and refine your patent claims to highlight the novel aspects. A good search can also help avoid infringing on others’ patents and save you from pursuing an idea that isn’t patentable.

Using the USPTO’s Patent Public Search Database:

In 2022, the USPTO launched its modern Patent Public Search system, replacing the old tools (like PubWEST and Public PAIR). This database integrates over 11 million U.S. patent documents and allows advanced search queries. It’s the most authoritative source for U.S. patent information, updated daily. Best of all, it’s free to use via the USPTO website.

Step-by-Step Search Process:

- Start with broad keywords: Begin by searching for simple keywords that describe your invention. Think of terms for its function or purpose. For example, if your product is a new water filter, start with terms like “water purification filter” or “water filtration device.”

- Refine using classification codes: The USPTO (and international patent offices) organize inventions by technical categories. Find the relevant Cooperative Patent Classification (CPC) or International Patent Classification (IPC) classes for your technology. For instance, water filters might fall under CPC class B01D (separation processes) or C02F (treatment of water, waste water, sewage). You can search within these classes to uncover patents you might miss with keywords.

- Search by inventor or assignee: If you know of companies or individuals active in your field, search for their patents. For example, if you’ve invented a new AI-powered recommendation system, check what Amazon, Netflix, or Google has patented in that space.

- Use Boolean operators: The patent search interfaces support advanced queries:

- AND – to require multiple terms (e.g., filter AND membrane AND reverse osmosis).

- OR – to broaden search with synonyms (e.g., battery OR “energy storage”).

- NOT – to exclude things not of interest (e.g., drone NOT military if you want consumer drones).

- Wildcard () – to catch variations (e.g., sensor will catch sensors, sensory, etc.).

- Review patent claims carefully: When you find a potentially relevant patent, read its claims (especially independent claims). The claims define the legal scope. Ask: Which elements overlap with my invention? Identifying differences will help you craft your own claims to emphasize novelty.

- Check patent families: Many inventions have multiple related filings (continuations, foreign counterparts via the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT), or other national filings). The USPTO Public Search and other tools, such as Espacenet, will show “family” information. This can lead you to foreign-language prior art or to additional technical details in related publications.

Effective Search Strategies:

Keyword development: Make a list of synonyms and related terms. Inventors often use different terminology. For example, for AI-related inventions, search “machine learning,” “neural network,” “deep learning,” “artificial intelligence,” and “predictive model” to capture various approaches to similar problems.

Use multiple databases: In addition to the USPTO’s database, try Google Patents, which has a user-friendly interface and covers international patents. Google’s search algorithm can sometimes find related patents via semantic search that you might miss by manual queries. Also consider:

- WIPO’s PATENTSCOPE: for PCT international applications

- European Patent Office’s Espacenet: for European and worldwide coverage

- Other national databases (if relevant), such as J-PlatPat (Japan) and CNIPA search (China, though language may be a barrier), etc.

Non-patent literature: Don’t forget to search academic papers, technical standards, product literature, etc. If your field is highly technical, examiners will also consider journal articles or technical disclosures as prior art.

When to Consider Professional Patent Search Services:

If your invention is in a very crowded or complex field, or if you’re about to invest significant resources, it might be wise to hire a professional patent search firm or a patent attorney to perform an exhaustive search. Professionals have expertise in digging through classification systems and may uncover obscure prior art (especially foreign patents or non-English publications) that a DIY search could miss. Professional patent searches typically cost $500 to $2,000, depending on complexity, but they often provide a detailed report of relevant references. This can be invaluable for honing your invention’s unique point of novelty.

Documenting Your Search Results:

Keep a search log or spreadsheet. Record the patent numbers or publication numbers you looked at, a brief note of their relevance, and how your invention differs. Note key dates (a prior art reference must pre-date your filing). This documentation not only helps you draft the application but is also useful if you later consult a patent attorney. It shows you’ve done diligence and can speed up their understanding of the landscape.

In summary, don’t skip the search. Many first-time inventors are tempted to go straight to filing, but a comprehensive search can save you from pursuing an idea that’s already patented or help you focus your claims on what’s genuinely new. It’s a critical investment in time that can make or break your patent’s success.

Choose the Right Type of Patent Application

Selecting the appropriate type of patent application (and patent) is crucial for obtaining the proper protection for your invention. The USPTO offers different application pathways and patent types, each serving specific purposes and offering distinct advantages. Let’s break down the main options:

Utility Patents vs. Design Patents:

Utility Patents protect how an invention works or is used. This is what people typically mean by “patent”—it covers processes, machines, manufactured items, compositions of matter, or any new and useful improvements thereof. A utility patent gives you the right to exclude others from making, using, or selling the invention’s functional aspects for 20 years from the filing date (for applications filed after June 8, 1995, under current law). Most technology and product inventions fall in this category.

Examples: The touchscreen functionality of a smartphone, a new chemical polymer, AI algorithms that solve technical problems, SaaS architectures that improve system performance, or machine learning models that enhance data processing—all are proper subjects for utility patents.

Design Patents protect the ornamental design or appearance of an article of manufacture. They do not explain how the article works; they only show how it looks. Design patents are beneficial for consumer products with distinctive shapes or surface ornamentation. A design patent lasts 15 years from issuance (for design applications filed after May 13, 2015).

Examples: The unique shape of a Coca-Cola bottle or the iconic design of the original iMac computer casing are protected by design patents. Another modern example: Apple’s iPhone design—Apple has design patents on the iPhone’s rounded rectangle shape and icon grid layout, separate from its utility patents on the device’s functionality.

Strategic Considerations:

If your product has both novel functional features and a unique appearance, you might pursue both types of patents. Many companies do this to build a stronger IP portfolio. For instance, automobile manufacturers patent the functional improvements in an engine (utility) and also patent the car’s headlamp shape or grille design (design).

Note that design patents are generally easier and quicker to obtain (often no rejections if the design is clearly novel) and cheaper to file/maintain than utility patents. In fact, design filings have grown in popularity—the USPTO issued its 1,000,000th design patent in September 2023, and annual U.S. design patent application filings have increased by approximately 20% over the past five years, topping 50,000 in 2021 and 2022. This trend reflects companies recognizing the value of protecting product aesthetics alongside functionality.

Provisional vs. Non-Provisional Applications:

Provisional Patent Application: A provisional application is an inexpensive, temporary placeholder that establishes an early filing date for your invention without starting the examination clock. Provisional applications were introduced in 1995 to help inventors secure a filing date quickly and inexpensively. Key features:

Lower upfront cost: The USPTO filing fee for a provisional is much lower than for a full application (currently $60 for micro entities, $150 for small entities, $300 for large entities). Note: these fees were reduced in 2023 from previous amounts, making provisional filings even more affordable for small entities.

No examination: A provisional is never examined or granted as a patent by itself. It simply holds your place in line. You have up to 12 months to convert it by filing a corresponding non-provisional (utility) application that claims priority to the provisional. If you miss the 12-month window, the provisional lapses and never turns into a patent.

“Patent Pending” status: Once you file a provisional, you can legally say “patent pending” on your product or marketing. This can deter competitors and impress investors, even though the application isn’t yet examined.

Flexibility to refine: The provisional buys you time to develop further or test the invention, seek feedback, or raise funds before committing to the full cost of a non-provisional. Many startups use this strategy to secure an early date and then see if their concept has market traction before investing in a full patent. This is particularly valuable for SaaS founders who are iterating on their platform or AI developers refining their algorithms.

Business Value Beyond Filing Date: Provisional applications provide concrete legal protection superior to vague NDA agreements. Most sophisticated companies actually REQUIRE inventors to file provisional applications before discussing inventions—this protects them from idea-submission lawsuits. Even during the provisional phase, ‘patent pending’ status creates immediate monetizable assets for licensing, collateral, and balance sheet value, while demonstrating serious IP development to investors, partners, and customers.

No formal patent claims required: Provisionals are generally easier to prepare—they don’t need formal claim language or certain other formalities. However, it’s critical that the provisional fully describes your invention, as filed, since only what’s disclosed will get the benefit of the date. You can’t add new matter later.

Significant limitations: A provisional alone will never result in an issued patent. It’s only a temporary measure. Also, the 12 months cannot be extended. If you fail to file a non-provisional in time, you lose the benefit of that early date. Finally, foreign patent offices generally do not recognize U.S. provisional filings directly, but filing a provisional can preserve your right to later file internationally under the Paris Convention (more on that later).

Non-Provisional (Regular) Patent Application: This is the “real” patent application that gets examined by the USPTO and can mature into an issued patent. When people talk about filing a patent application, they usually mean a non-provisional. It requires a complete set of sections (specification, claims, drawings, abstract) and full USPTO fees (filing, search, examination). Once filed, it is put in the examination queue. The filing date of the non-provisional is what ultimately starts the 20-year patent term clock for a utility patent. (If you claimed priority to a provisional, you effectively get the benefit of the earlier date for what was disclosed, but the 20-year term still counts from the non-provisional’s filing.)

When preparing your initial application, whether provisional or non-provisional, it is essential to include all required components to secure your filing date and ensure the application is complete for review.

When to Use Each:

Use a Provisional when:

- You need a quick filing date (e.g., you are about to do a public demo, pitch to investors, or launch a beta version and want to file before that).

- You are still refining the invention or writing the whole application, but want to lock in the date for what you have.

- You have budget constraints initially—a provisional can be done cheaply to buy time.

- You intend to label “patent pending” during business discussions, pilot manufacturing runs, or fundraising conversations.

- You are considering foreign patents—a U.S. provisional lets you claim priority internationally within 12 months.

File Non-Provisional (Utility) when:

- Your invention is fully developed, and you’re ready for examination.

- You desire the patent as soon as possible and don’t want to wait.

- The one-year deadline from a provisional or public disclosure is due—you must file a non-provisional to preserve rights.

- You’re not interested in a provisional because you prefer to go straight to the actual patent process (some companies skip provisionals if they have the budget and clarity on the invention).

Many inventors start with a provisional and then file a non-provisional 6–12 months later. This is a common strategy to maximize your effective patent term (since the provisional period doesn’t count against the 20 years) and to iterate on the invention. Just remember: when you file the non-provisional, make sure it includes everything from the provisional and any improvements. You can file multiple provisionals as you improve aspects, and then combine them into one non-provisional (by correctly referencing each provisional) within the year.

Lastly, note that design patents do not have provisional applications—provisionals are only for utility-type inventions. If you have a design, you go straight to a design patent application (which is simpler and cheaper than a utility patent anyway). For assistance with your application, consider consulting Andrew Rapacke, a registered patent attorney.

In summary, choose Utility vs. Design based on whether your invention’s uniqueness lies in its function or its form (or both). And choose Provisional vs. Non-Provisional based on your readiness and the balance between speed and cost flexibility. It’s not either/or for all cases—you might file a provisional utility application for the functionality and simultaneously file a design application for the product’s look, covering both bases.

Prepare Your Patent Application Documents

Once you’ve done your homework on patentability and searches, the next step is preparing the patent application itself. Crafting a complete and high-quality application is vital—the details can determine whether you get a strong patent, a weak patent, or no patent at all. The USPTO has strict rules on format and content, so let’s break down the required components and common pitfalls to avoid.

Required Application Components:

1. Patent Specification:

This is the main written description of your invention. It should be complete and transparent such that a person skilled in the field can read it and understand how to make and use the invention (this is called the “enablement” requirement under 35 U.S.C. § 112). Key parts of the specification include:

- Title – A short, descriptive title of the invention (typically under 10 words). Example: “AI-Powered Content Recommendation System” or “Cloud-Based Data Synchronization Method.”

- Cross-References to Related Applications – If this application claims priority to any prior application (like a provisional or another non-provisional), or is a continuation/divisional of an earlier application, you cite that here.

- Background – A section describing the state of the art and the problem that your invention addresses. Explain the shortcomings of existing solutions. This sets the stage for why your invention is needed. Avoid admitting too much (“the prior products are all terrible”) because that can be used against you, but be honest about context.

- Summary of the Invention – A brief overview of the invention’s key features and innovations, written broadly. Think of this as the elevator pitch of what your invention is and what it achieves.

- Brief Description of the Drawings – (If you have drawings), a one-sentence description of each figure in the patent drawings.

- Detailed Description – This is the heart of the specification. You describe in thorough detail how the invention works, referencing the drawings by figure numbers and reference numerals. Include specific examples or embodiments. Ideally, provide alternative embodiments or variations as well—this helps broaden your coverage and show that you’ve contemplated different implementations. If it’s a device, describe each component and how they interact. If it’s a process, walk through each step. The idea is to leave no significant question unanswered about making or using the invention.

- Optional sections such as Definitions (if you need to define terms), Experimental Results (if applicable, e.g., data demonstrating an improvement), etc.

Applicants may also include additional information or supplementary details in the application to clarify aspects of the invention. Providing such additional information can help address potential questions during the review process and ensure the examiner fully understands the invention.

Tip: Write the specification for someone skilled in the art but who hasn’t been in your head—you need to teach them from scratch. Use precise language and reference numbers consistently (e.g., “spring (10) is attached to lever (12)”). Avoid marketing language or vague terms. More detail is usually better, as long as it’s relevant, because you cannot add new matter after filing. Ensure the disclosure supports everything you later claim as your invention.

Claims are the legal definition of your invention. They are arguably the most essential part of the application, and also the trickiest to write. The claims appear at the end of the specification and consist of numbered statements (each a single sentence) that delineate the boundaries of your invention.

- Independent claims stand on their own and define an invention without reference to another claim. They are broad in scope. Every patent must have at least one independent claim (often you’ll have 2-3 covering different aspects).

- Dependent claims refer back to an earlier claim and add further limitations or details. These serve to provide fallback positions—if your broad claim is rejected, a narrower dependent claim might be allowed.

Example: If your invention is a new kind of umbrella, an independent claim might be: “A collapsible umbrella comprising: a canopy made of waterproof fabric; a set of rib supports pivotally attached to a central shaft; and a spring mechanism configured to automatically deploy the canopy when a button is pressed on the shaft.” A dependent claim could add: “The collapsible umbrella of claim 1, wherein the waterproof fabric is a multilayer polymer with UV-protective coating.”

Claim drafting principles: Use precise language. Each claim is like a checklist of features—if someone has a product with all those features, they infringe. If even one feature is missing or different, they do not infringe. So choose words carefully and anticipate design-arounds. Avoid unnecessary words (“essentially”, “approximately”) as they introduce ambiguity—the patent office might reject claims as indefinite if terms aren’t clear. Define any specialized terms in the spec. Also, aim for claims of varying scope: some broad to stake out territory, some narrow to ensure you have something allowable over prior art.

It’s common for first-time applicants to write claims either too narrow (basically describing one exact embodiment, which doesn’t protect variations) or too broad (covering things the inventor didn’t actually invent, leading to obviousness rejections). Striking the right balance often requires experience or professional guidance. Pro Tip: Review patents in your field and study their claim language to get a feel for the phrasing.

3. Patent Drawings:

“A picture is worth a thousand words” is very accurate in patents. Drawings are required when necessary to understand the invention—practically, most applications include drawings, except perhaps for purely chemical or mathematical inventions. USPTO drawing rules include:

- Use black ink on white paper (or the electronic equivalent). Shading is allowed, but no color or grayscale for utility patents.

- Show all critical elements of the invention in various views (front, side, exploded view, flowchart, whatever is relevant).

- Label each part with a reference number and mention those numbers in the detailed description.

- Drawings must be formal (line drawings). You can start with rough sketches, but the final submission should meet formal standards (no annotations, clear lines, proper margins).

If you’re not experienced at technical illustration, consider hiring a patent drafting technician. Professional patent drawings typically cost $75–$150 per figure for simple cases (more for complex cases), but they ensure compliance with USPTO rules (e.g., line thickness, numbering, reference arrows, etc.). Many applications get objections for drawing informality—a pro can save hassle.

4. Abstract:

A summary of the disclosure, 150 words or fewer. Think of it as the blurb that will appear in patent databases to help readers quickly grasp what your invention is. The abstract is not used for examination on merits, but it should concisely describe the main invention and key technical features. Avoid legalese or claim-like wording here. For example: “An autonomous robotic lawn mower that uses machine vision to detect obstacles and dynamically adjust its cutting path. The mower includes sensors, a microcontroller, and an adaptive blade height mechanism for varied terrain.”

Common Application Mistakes (and how to avoid them):

Insufficient Detail: One of the most common reasons patent applications get rejected (or issued patents get invalidated later) is a lack of detail or lack of enablement. If an examiner (or later, a court) feels that your description doesn’t teach how to make and use the full breadth of what you claimed, you’re in trouble.

Fix: When in doubt, add more description and examples. If you have experimental data or prototypes, describe them. Cover edge cases. Ask a colleague if they could replicate the invention from your description alone. This is where experienced patent prosecution makes the difference—novice attorneys and DIY inventors often lack the calibration to know what level of detail the USPTO requires. At Rapacke Law Group, our years of experience drafting applications in tech fields mean we know exactly how much detail satisfies enablement requirements while protecting your competitive position.

Inconsistent Terminology: Using multiple terms for the same component can create confusion. For instance, don’t call it a “widget” in one sentence and a “tool” in another if it’s the same item. Consistency is key. Consider including a glossary or definitions section if you have many acronyms or technical terms. Also, ensure the terms in claims are supported by the spec (if you claim a “frusto-conical gear,” make sure the spec or drawings mention that term or clearly depict it).

Overly Broad Claims: It’s tempting to claim the world (“I claim a transportation device comprising an engine and wheels”—trying to patent cars in general). But examiners will hit broad claims with prior art. Try to identify what is genuinely new and focus claims around that. You can have a broad, independent claim, but be prepared —it might be narrowed. One strategy is to include a mix of broad and more specific independent claims (if budget allows additional claim fees) to see what sticks.

Omitting Key Alternatives: If your invention has possible variations (different materials, shapes, etc.), mention them. For example, if your invention is a “metal alloy spring,” consider whether plastic could also work and say so. Otherwise, a competitor might make a trivial change (use a plastic spring) and argue your patent doesn’t cover it because you only taught metal springs. Cover foreseeable alternatives in the description and maybe in dependent claims.

Failing to Meet Formalities: The USPTO has many formal rules—such as margin size, proper section headings, and claim numbering. If you file without meeting these requirements, you might get a Notice of Missing Parts or other delays. Use the USPTO’s checklists or a service that formats applications. If you’re drafting yourself, carefully read the Manual of Patent Examining Procedure (MPEP) chapters on application format, or look at an issued patent in a similar field as a template for structure.

Remember, the goal of the application is twofold: satisfy the legal requirements (so the USPTO can grant the patent) and provide strong protection (so it’s hard for others to design around or invalidate). It’s a delicate blend of legal writing and technical teaching. If you are not confident, this is a stage where consulting a patent attorney or agent, at least for a review, can be extremely helpful.

File Your Application with the USPTO

Once your application documents are prepared, the next step is to formally apply to the United States Patent and Trademark Office. The USPTO strongly prefers electronic filing, and as of late 2025, it’s essentially mandatory for most applicants. Here’s what you need to know about the filing process:

USPTO Electronic Filing (Patent Center):

The USPTO’s online filing portal, Patent Center, has entirely replaced the older EFS-Web system. Patent Center is a one-stop dashboard where you can upload application documents (specification, claims, drawings, etc.), pay fees, and track your application status. You’ll need to create a USPTO.gov account and verify your identity to use it. (Identity verification involves confirming your identity with USPTO—usually by a video interview or using a service—a step implemented in recent years to enhance security).

Starting September 2025, electronic filing is required for patent applications except in extraordinary circumstances (per USPTO rules)—paper filings incur a hefty non-electronic filing surcharge of $400 (which is not discounted for small entities). So, practically speaking, plan to file online.

What You Need to File: When you go to file, ensure you have the following ready:

Application Documents: Your specification, claims, abstract, and drawings in the proper format. The USPTO now encourages filing text components in DOCX format (instead of PDF) because it allows automated checks and reduces transcription errors. In fact, as of January 2024, the USPTO requires a DOCX filing or charges an extra fee for PDFs. The Patent Center will generate a validation report if any issues are found (e.g., unsupported fonts, improper equations) before final submission.

Applicant Information: Names, addresses, and citizenship of all inventors. Make sure the inventor’s names on the application match exactly what’s on their legal IDs (to avoid discrepancies).

Application Data Sheet (ADS): This is a form (or electronic entry) where you provide bibliographic data—inventor info, correspondence address, whether you’re claiming priority to any earlier applications (like a provisional or foreign patent application), etc. It’s essential to get the ADS right because it establishes matters such as priority claims and your small-entity status election.

Entity Status Certification: If you are filing as a small entity or micro entity (to get fee discounts), you need to assert that status. A small entity is typically a company with ≤500 employees or an independent inventor. Micro entity status has additional requirements: you qualify if you have no more than four prior patents, have a gross income below a certain threshold (~$212k for 2023), and haven’t assigned rights to a large company. Micro gets you an 80% fee reduction; a small entity receives a 60% reduction.

Fees: You must pay at least the filing, search, and examination fees upon filing, or your application won’t get a filing date. (The USPTO will accept an application without fees and issue a Notice to pay, but the official filing date is when all required parts and fees are received.) As outlined earlier, the basic combined fee is $1,600 for a small entity, $640 for a micro entity, and $3,200 for a large entity. If you have excess claims beyond 20 total or more than three independent claims, additional fees apply (e.g., $100 for each claim over 20 if a large entity, $50 if small)—the Patent Center will calculate these as you input your claims. If your specification is very long (over 100 pages) or you have numerous drawings, there can be size fees as well. All fees can be paid by credit card or via an online USPTO deposit account. Make sure to pay the correct amount; an underpayment can cause delays.

Inventor Oath/Declaration: Each inventor must sign an oath or declaration stating that they believe themselves to be the original inventor. In practice, you can file the application first and submit the signed declarations shortly after (the USPTO will issue a notice and a time window to file them if they are not submitted initially). There’s a standard USPTO form for this (Form AIA/01). If you’re using Patent Center to auto-generate the declaration, it will fill in the info for the inventors to sign.

Filing and Confirmation: When you submit through Patent Center, the system will give you an application number and a filing date (if all parts are present). You will typically receive an email with an electronic filing receipt within a day or two, listing key details such as the filing date, application number, title, inventors, etc. Review it carefully to ensure everything is correct (especially priority claims and the spelling of names). Mistakes on a filing receipt can often be corrected, but it’s best to catch them early.

A complete, proper filing includes, at a minimum:

- A specification (with at least one claim).

- Any required drawings.

- The filing fee (or at least an authorization to charge fees).

- Inventor information and an address for correspondence.

When it comes to who can apply, inventors have several options. You may file the application yourself (pro se), work with a registered patent attorney, or choose to work with a registered patent agent. A patent agent is authorized to file patent applications and represent inventors before the USPTO, assisting in the process.

Suppose something critical is missing (like you forgot to include claims entirely, or omitted drawings that are described as essential). In that case, the USPTO may give you a filing date but then send a Notice of Missing Parts, or even not accord a date until the missing parts are fixed (worst case, a Notice of Incomplete Application). A typical scenario: forgetting to submit the fee or the oath—usually, these can be fixed by paying a surcharge within a given time.

After Filing – What Happens:

Your application will be entered into the USPTO’s system. Here’s what happens next:

Initial Processing: The application goes through an initial formalities review. The office will check whether all pages are present, whether the drawings comply with the form, and so on. Suppose something like an inventor declaration or the application data sheet is missing or defective. In that case, they’ll send a notice (usually a “Notice of Missing Parts”) giving you a deadline (often 2 months) to fix it, typically with a small surcharge fee (e.g., $80 for micro, $200 for small entity).

Publication: By default, non-provisional patent applications are published 18 months after the earliest priority date (unless you file a request to opt out because you aren’t planning foreign filings). Publication means the public can see your application. If you want to keep it secret (and you’re not going international), you can request non-publication at the time of filing. However, if you later change your mind and file abroad, you need to notify the USPTO within 45 days of the foreign filing, or you risk abandonment.

Waiting for Examination: After about 8–12 weeks, you’ll see in Patent Center that your application has been assigned to an Art Unit and an Examiner (art units are groups of examiners specialized in certain technologies). However, actual examination will not begin until your application’s turn comes in the queue, which can be a year or more later for most technologies. As of late 2024, the average time to first Office Action for utility applications was ~20 months, but it varies (e.g., some fast-moving fields like AI or software might wait ~2 years, while some mechanical arts might wait ~1 year). Design applications are often faster; many receive a first action within 12 months due to lower volume.

Patent Pending Status: From the moment you get your filing confirmation, your invention is patent pending. You should mark products or materials with “Patent Pending” if applicable. This doesn’t yet give you the legal right to sue, but it puts others on notice that you have an application on file.

Key Tip: Double-check everything before hitting submit—especially that your claims and drawings are included, and that you uploaded the correct files (people have accidentally filed the wrong PDF or an earlier draft). Also, ensure any foreign priority or provisional application numbers are correctly listed on the ADS, because if you miss claiming priority, you could lose that earlier date.

Filing a patent application is a significant milestone—congratulations! It officially sets the wheels in motion for examination. Next, we’ll cover what to expect during the examination process and how to navigate communications with your examiner.

Navigate the Patent Examination Process

After filing, your application enters the USPTO’s examination queue. The patent examination process (also called patent prosecution) is where a patent examiner reviews your application in detail to determine if a patent can be granted. Understanding this process will help you manage expectations and respond effectively to any issues that arise.

Initial USPTO Processing: As mentioned, your application will be assigned an Art Unit based on its subject matter and then placed in a queue for an examiner. The wait time for the first action varies—it can be as short as 6 months in some cases or as long as 2 years in others. The USPTO’s First Office Action Pendency was about 20.2 months on average in 2024, but with new hiring and initiatives, they aim to reduce this. (For instance, the USPTO hired 850 new patent examiners in FY2024 to tackle the backlog.)

If you’re anxious about the wait, note there are ways to expedite (discussed later), but otherwise it’s a bit of a “hurry up and wait” scenario once filed.

First Office Action: When your application is reviewed, the examiner will conduct their own prior art search and issue an Office Action. The first communication is often a Non-Final Office Action. It will typically contain:

- References found: The examiner will cite patent documents (and sometimes scientific papers or web articles) they believe are relevant.

- Rejections or Objections: Don’t be alarmed—it’s normal to get rejections in the first Office Action. In fact, very few patent applications are approved immediately without any examiner objections. Historical USPTO data shows that only about 11% of applications filed between 1996 and 2005 were allowed on the first action without any rejection. Most applicants go through at least one round of back-and-forth.

Common types of rejections:

- §102 (Anticipation): One reference is found that, in the examiner’s view, fully discloses your claimed invention. This is a novelty rejection (“Smith et al. Patent anticipates your claim 1 because Smith shows every element you claimed.”).

- §103 (Obviousness): The examiner has combined two or more references to show your invention is an obvious combination. This is the most common type of rejection. They might say, “Reference A shows most of your claim, and Reference B shows the rest; it would have been obvious to combine A and B.” This is the single most challenging rejection type to overcome—determining what’s ‘obvious’ requires years of calibration that DIY inventors and novice attorneys simply don’t possess. Our experienced patent attorneys have developed sophisticated legal doctrines to overcome obviousness rejections, with strategies that must be ‘baked into the cake’ from the initial filing. This expertise is why our allowance rates consistently exceed industry averages.

- §112 issues: If your claims are unclear (indefinite) or the spec lacks support for something, the examiner can reject on these grounds too. E.g., “Claim 5 is indefinite because the term ‘highly efficient’ is subjective” or “The specification does not enable the full scope of claim 10.”

- Formal objections: Sometimes drawings or minor issues are objected to—like reference numbers not matching, or an abstract that’s too long. These are usually easy fixes.

It’s essential to read the Office Action carefully. The examiner will provide a detailed explanation for each rejection, often referencing specific columns and lines of the cited patents that allegedly correspond to your claim elements.

Responding to Office Actions:

You (or your attorney/agent) typically have 3 months to respond to an Office Action. You can extend this term up to 3 additional months by paying extension fees. For example, a one-month extension for a micro entity costs $47, and for a small entity $ it costs $94. It gets more expensive for longer extensions (e.g., a 3-month extension for a large entity is $1,590). It’s best to respond within three months to save money and demonstrate diligence.

In your response, you have a few options:

Amend the Claims: This is most common. You can narrow or clarify your claims to overcome prior art or objections. E.g., if the examiner found a reference that has everything except one detail, you might amend claim 1 to include that distinguishing detail explicitly. All amendments must be made with proper marking (new text underlined, deleted text [bracketed]) in the response.

Argue Against the Rejection: You provide reasoning why the examiner is wrong or the prior art doesn’t actually teach what they think. For instance, you might argue that Reference A does not actually disclose the claimed feature, or that the combination of A and B is not obvious because they teach away from each other or yield unexpected results.

Do Both: Often, a balanced approach is to make some claim amendments and provide arguments. This shows you’re willing to compromise by narrowing some, but also that you believe your invention has differences that should be recognized.

Interviews: You can request an examiner interview (by phone, video, or in person) to discuss the case. This can be very effective in understanding the examiner’s thinking and potentially finding a path to agreement. Many examiners appreciate a collegial discussion. After an interview, you or the examiner will record a summary in the file.

After Final Options: If the Office Action was marked “Final” (usually the second round, if the examiner is not satisfied with your first response), your options narrow. You can’t freely amend without either filing a Request for Continued Examination (RCE) (with a fee) or appealing. Often, after a final rejection, applicants file an RCE, which gives them another bite at the apple (the prosecution is reopened as non-final). The RCE fee for a small entity is currently $600 (micro $300). Alternatively, you can appeal to the Patent Trial and Appeal Board if you think the examiner is clearly wrong and further arguments won’t help.

Examiner’s Perspective: It helps to remember that examiners are graded on their disposition of cases and have limited hours to examine each application (though the USPTO increased the time per application in 2019 to improve quality). If your case is complex or borderline, a well-crafted response that makes the examiner’s job easier (e.g., by clearly pointing out distinctions in claim language and prior art) can go a long way. Being respectful and transparent in arguments is key—you’re effectively trying to persuade a technically skilled person of your viewpoint.

Allowance and Issue: If the examiner is convinced—either immediately or after some back-and-forth—that your claims are patentable, you’ll receive a Notice of Allowance. Congrats! This notice lists any allowed claims and calculates the Issue Fee you owe. The issue fee for a utility patent (as of 2025 fee update) is $1,290 for large, $516 for small, and $258 for micro. You have 3 months to pay the issue fee (no extensions). After payment, the USPTO will issue the patent in the next available weekly batch, and you’ll get a ribbon-sealed certificate in the mail.

Patent Grant: Once granted, the patent is published with a patent number, and the invention is officially patented. Remember, maintenance fees will come due down the road (for utilities), as mentioned earlier. Also, any continuation applications or related filings should ideally be filed by the issue date if you want to pursue broader claims, since after issuance, prosecution on that application is closed.

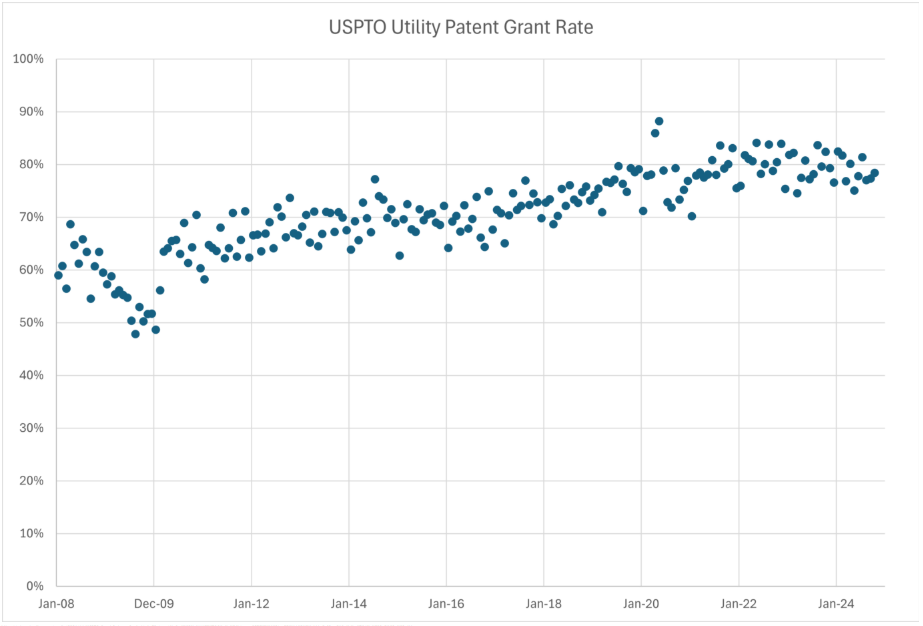

Reality Check: Most patent applications go through multiple Office Actions. Statistics show that the overall allowance rate has been around 75–85% in recent years, meaning most eventually get patented, though often with some narrowing of claims.

However, allowance isn’t the only measure of success—not all patents are created equal. Weak patents that get allowed after excessive narrowing create roadmaps for competitors to beat you faster and cheaper. The goal isn’t just getting a patent; it’s getting a patent engineered to withstand scrutiny and deter competitors from designing around your innovation.

Persistence is key—as long as you can distinguish over prior art, you have a good shot. However, if the prior art is very close and you can’t get allowable claims, you might decide to abandon the application. It’s not the end of the world; sometimes the exercise of filing reveals an invention isn’t as groundbreaking as hoped. But often, by creatively adjusting claim scope, inventors and examiners find an acceptable middle ground.

Expedited Examination Options: If the normal process is too slow for you, consider:

Track One Prioritized Examination: By paying an extra fee (currently $4,515 for large, $1,806 for small, $903 for micro), you can get on a fast track. Track One aims for a final decision within 12 months of filing. There are limits (e.g., you can’t have too many claims). Interestingly, Track One applications have a higher allowance rate (about 89% vs 70% for regular ones), possibly because applicants use it for their strongest cases, and the quicker feedback allows for faster iteration.

Petition to Make Special: There are specific categories where you can petition for an accelerated exam without a fee—e.g., the inventor’s age (65 or older), or health (if you can show health reasons), or if the invention is of particular importance to public safety or the environment. Recently, the USPTO also launched initiatives for specific technologies: as of 2024, it offers free expedited examination for first-time inventors and in areas of national priority, such as semiconductors, green energy, and cancer research. These programs can significantly cut down wait times if you qualify.

Patent Prosecution Highway (PPH): If you filed in another country and got some claims allowed there, you can fast-track the U.S. application by showing those allowed claims (and vice versa). The U.S. has PPH agreements with many patent offices.

Overall, navigating the examination requires both technical acumen and legal strategy. Don’t be discouraged by rejections—they are part of the process. Be prepared to adapt and advocate for your invention with solid reasoning. And always keep an eye on the clock and deadlines, because the USPTO is unforgiving on missing due dates (a missed response deadline can result in abandonment, which might be reversible but will cost fees and require a valid reason).

Working with Patent Professionals

At this stage, inventors face a pivotal decision: whether to hire a patent attorney or go it alone. While the USPTO allows inventors to file “pro se” (without representation), the data and real-world outcomes make one thing clear — partnering with an experienced patent attorney is almost always the smarter investment.

When to Hire a Registered Patent Attorney:

A patent lawyer (another term for a patent attorney) can assist with drafting complex patent claims and provide legal representation throughout the patent process.

Technical Complexity: If your invention is highly complex (say, an AI algorithm, a biotech invention, advanced electronics, or a SaaS architecture), a patent professional with expertise in that domain can significantly enhance the quality of your application. They’ll know how to phrase claims to capture the invention best and avoid pitfalls. For example, software patents post-Alice require careful claim drafting to meet the eligibility criteria—professionals stay up to date on these nuances.

High Commercial Stakes: If the invention could be a core business asset worth millions, the cost of an attorney is usually justified by the importance of getting a solid patent. Think of it as an investment: a strong patent can attract investors or deter competitors; a weak one might be effectively useless. Many companies allocate a portion of their R&D budget to IP protection for this reason.

Desire for Global Protection: Filing in the U.S. is one thing, but if you want patents in Europe, Asia, and other regions, an attorney can coordinate that strategy. They can file PCT (Patent Cooperation Treaty) applications and foreign national applications, and manage counsel in each jurisdiction.

Prior Art Landmines: If your preliminary search found a lot of close prior art, an experienced practitioner can do a patentability opinion and figure out how to differentiate your claims. They know what arguments tend to work with examiners and how to avoid writing something that inadvertently reads on prior art.

Time Constraints: Writing and prosecuting a patent can be extremely time-consuming, especially if you’re learning as you go. If your time is better spent on developing the product or business, outsourcing to a professional might be prudent.

The RLG Advantage:

At Rapacke Law Group, we understand the unique challenges SaaS founders and tech innovators face. Unlike traditional hourly billing, which can spiral out of control, we offer transparent, fixed-fee pricing for patent services. You’ll know exactly what you’re investing upfront—no surprise bills, no meter running while you ask questions.

The RLG Guarantee means you’re protected: We’re so confident in our approach that we offer full refunds if your provisional patent application is denied, or if patentability issues arise during our search process. This guarantee, combined with our specialization in tech IP and fixed-fee transparency, makes us the go-to legal partner for tech startups and inventors who need patents that actually protect their innovations—not just paperwork that satisfies USPTO formalities.

Our specialized expertise in AI and software patents keeps us current with evolving USPTO guidelines and enables us to strategically position your claims to maximize protection while minimizing §101 eligibility challenges. We’ve helped hundreds of tech startups secure strong patent portfolios that attract VC funding and deter competitors.

Cost Reality Check:

These costs are not trivial, but consider that pro se applicants historically have had much lower success rates. A famous study from Harvard Law School (2012) found that 76% of pro se patent applications were abandoned without issuance, compared to about 35% for those with representation. The lesson is clear: attempting to save money upfront on professional legal representation often leads to wasting far more time and money pursuing applications that ultimately fail. Those ‘savings’ evaporate when you have no patent protection after years of effort, while competitors freely use your disclosed invention. Quality legal representation isn’t an expense—it’s an investment that typically saves money in the long term by avoiding failed applications and securing stronger, more valuable patents.

Finding the Right Practitioner:

- Use the USPTO’s Registered Patent Practitioner database on their website to find attorneys or agents.

- Look for someone with experience in your technology area. Patent law is specialized, and many attorneys have technical backgrounds.

- Take advantage of a consultation: many offer an initial consult for free or a small fee to discuss your case and provide an estimate.

Alternative and Pro Bono Resources:

USPTO Pro Se Assistance Center: The USPTO does provide some help for inventors filing on their own. They have a dedicated helpline and email, and often will hold outreach programs or webinars for pro se filers. Check the USPTO Inventor Resources page for more information.

Patent Pro Bono Program: The USPTO coordinates a nationwide pro bono program with regional organizations. If you qualify as a low-income inventor or small business, you could get matched with a volunteer patent attorney for free or at a reduced cost. As of 2023, over 3,800 inventors have been matched through this program since its inception, and nearly 2,000 patent applications have been filed for free on their behalf.

Law School Clinics: Over 60 law schools in the U.S. have IP clinics certified by the USPTO. Law students (supervised by licensed professors) can assist in drafting and prosecuting your application for free or just the cost of filing fees.

Remember, a patent is a legal document that could be critical to your business’s success. The bottom line: weak patents help your competitors design around your invention, while strong patents force them to negotiate licenses or abandon their copycat plans altogether.

Patent Timeline and Cost Planning

It’s crucial to approach patenting with a realistic timeline and budget in mind. Patenting is not a one-and-done event, but a multi-year process with expenses along the way. Let’s outline the typical timeline from idea to issued patent and beyond, and discuss how to plan financially.

Typical Patent Timeline (U.S. utility patent):

Filing to First Office Action: ~1.5 years on average (18 months). As we discussed, this could be shorter or longer. By April 2024, the average first-action pendency was ~20.2 months. The USPTO is trying to reduce this by hiring examiners and making operational tweaks. Still, if you are in a fast-evolving tech field, you may see longer wait times due to higher filing volume (for example, AI-related applications ballooned recently, causing backlogs in those art units).

First Office Action to Allowance or Final Rejection: This can vary widely. You typically respond in 2–3 months, then the examiner may take 2–6 months to reply. If you get an allowance after one response, great—that might be within a year of first action. Often, it might take two Office actions (a non-final, then a final), which could take another year. So, from first action to final disposition, it might take another 1–2 years.

After Notice of Allowance: Pay issue fee, then ~2–4 months to actually get the patent issued (the USPTO has set issue cycles).

Total: For many cases, 2 to 4 years from filing to grant is typical. Highly contentious cases or those that go to appeal can take longer (5+ years). Some straightforward cases (especially in less crowded fields or expedited cases) can be completed in under 2 years.

For design patents, the timeline is usually faster: often 1–2 years total. In FY2023, the average time to issue a design patent was about 22.1 months.

Pendency vs. Market Realities:

Think about what this timeline means for your business. If you have a fast product cycle (like a SaaS platform that iterates quarterly), the patent might issue when the product has already evolved significantly. However, having “patent pending” can still be valuable during that time for investor conversations and competitive positioning, and the issued patent might protect improvements or the general concept even as you evolve.

For SaaS founders, this timeline underscores why early patent filing is critical—a strong patent portfolio can be the difference between a $10M valuation and a $50M valuation during Series A negotiations. Investors increasingly scrutinize IP protection as a key indicator of defensible competitive advantage and long-term business viability.

Cost Planning:

Let’s break down the costs over the lifecycle:

Upfront Filing & Preparation: If pro se, your costs are fees (e.g., ~$1,000 for a small entity) plus some drawing help. If using an attorney, upfront (search + drafting) might be $5k–$10k as noted. Make sure you budget for these at the outset. If you can’t afford it yet, maybe use a provisional (a few hundred dollars) as a placeholder while you save or raise funds.

Prosecution Costs: Each Office Action response might incur attorney fees if you use one. Also, there are USPTO fees if you need extensions or file an RCE ($138 micro for a 2-month extension, etc.; $572 micro for an RCE second request, etc.). These are sporadic, but plan a few hundred to a couple thousand over the course of prosecution.

Issue Fee: ~$600 for a small entity, payable at allowance.

Post-Grant (Maintenance Fees): Only for utility patents. As mentioned: due at 3.5, 7.5, 11.5 years. For a small entity currently: $860, $1,616, $3,312 at those milestones (these went up slightly in 2025). These are significant, especially the latter ones—many patentees choose to let patents lapse at 7 or 11 years if the technology is no longer valuable.

Total 20-year Cost Example: If you add it up for a small entity using an attorney, say $10k to get the patent + ~$2k issue/extension fees along the way + ~$5,788 in maintenance fees (860+1616+3312) = around $18k over 12 years. Spread out, but good to know. Micro would be less (maintenance total ~$2,894).

International Costs: If you plan to file elsewhere, budget generously. A PCT application filing is about $4,000 in government fees (depending on options) plus attorney fees to prepare (maybe $2k if they piggyback off your US app). Later, at the 30-month deadline, each country filing can be a few thousand dollars in translations and local attorney fees. It’s not surprising to spend $50k+ to get patents in, say, the US, Europe, China, and Japan.

Budgeting Tips:

- Consider the patent costs in your business plan. If you’re a startup, investors will expect you to have thought of IP. You can allocate $20k/year for the first few years for patenting if you have multiple innovations.

- Take advantage of discounts: Ensure you properly claim micro entity if you qualify—80% savings on many fees is huge. But note, if you license your invention to a big company, you may lose micro status.

- If funds are tight, stagger filings. Maybe file a provisional now, wait the max 12 months, file non-provisional—that buys a year. Or file one invention this year, another next year.

Tracking Deadlines:

Create a timeline for each application:

- 12 months from provisional → non-provisional due.

- 18 months → publication (if needed, file non-pub request at start or rescind if going foreign).

- ~2 years → expected first Office Action (set a tickler).

- Response due dates for each Office Action (enter them as soon as you receive an Office Action).

- Maintenance fee dates post-grant (3.5, 7.5, 11.5 yrs—easy to forget years later).

Finally, remember that obtaining a patent is not the end goal by itself—it’s a means to support your business or personal inventive goals. Plan not just for getting the patent, but also for how it will be used: Will you license it? Use it to secure investment? Use it as a defensive shield? For SaaS founders, a strong patent portfolio can be the difference between a $10M valuation and a $50M valuation during Series A negotiations.

Key Takeaway: Map out the patent journey early on a calendar and a spreadsheet. It will prevent unpleasant surprises and help you make informed decisions at each juncture. Patenting is a long game, but with proper planning, it can yield significant benefits and be managed cost-effectively.

Your Next Steps to Patent Protection Success

You’ve learned the complete patent process—from determining patentability through final grant. But knowledge alone won’t protect your invention. In today’s competitive landscape, where AI innovations emerge daily and SaaS platforms launch weekly, the gap between understanding the process and securing strong patent protection can cost you everything.

The bottom line: weakly drafted patents help your competitors design around your invention faster and cheaper, while strong patents—crafted with experienced patent prosecution and strategic claim drafting—force competitors to negotiate licenses or abandon their copycat plans altogether. This level of protection requires expertise that DIY inventors and inexperienced attorneys cannot replicate.

Here’s what’s at stake if you delay or take shortcuts:

Every day without patent protection is a day your competitors can study your innovation, reverse-engineer your approach, and file their own applications. In the first-to-file system, hesitation means losing your rights entirely. Even worse, a poorly drafted application—missing key claim language or failing to describe alternatives adequately—can result in a patent so narrow it’s worthless for enforcement. You’ll have spent thousands of dollars on a document that provides zero competitive protection.

Take these immediate action steps:

- Schedule a Free IP Strategy Call with our experienced patent attorneys to evaluate your invention’s patentability and develop a strategic protection plan customized for your specific technology and business goals.

- Document your invention thoroughly using the self-assessment checklist provided in this guide, and gather any prototypes, test data, or technical specifications that demonstrate how your invention works.

- Conduct or commission a professional patent search to identify prior art and understand the competitive landscape before investing in a full application.

- Decide on your application strategy (provisional vs. non-provisional, utility vs. design) based on your timeline, budget, and business needs.

- Prepare your filing with all required components or engage experienced counsel to ensure your application maximizes protection while minimizing examination challenges.

The RLG Guarantee for Provisional Patent Applications:

When you work with Rapacke Law Group on your provisional patent application, you get:

- FREE strategy call with our experienced patent team to discuss your invention and filing strategy.

- Experienced US patent attorneys lead your application from start to finish—no paralegals, no outsourcing.

- One transparent flat-fee covering the entire provisional patent application process (including office actions if any arise)—no hourly billing, no surprise costs.

- Full refund if USPTO denies your provisional patent application*.

- Complete refund or additional searches if your application has patentability issues (your choice)*.

*Terms and conditions apply. Contact us for full details.

Your competitive advantage depends on the strength of your IP portfolio. Investors know this. Acquirers know this. Your competitors definitely know this. The question is: will you secure that advantage before someone else does?

For AI innovations, SaaS platforms, and emerging tech, the window for patent protection is narrowing as competition intensifies. Download our AI Patent Mastery guide or SaaS Patent Guide 2.0 for specialized insights developed through hundreds of successful tech patent applications. Or better yet, schedule your free strategy call today and let our experienced patent team build a strategy that turns your innovation into a defensible competitive moat.

If we conduct the patentability search and find that your invention is not novel, we’ll issue a 100% refund.* The Patentability Search is the gateway to the patent process.

Connect with us: LinkedIn: Andrew Rapacke | Twitter/X: @rapackelaw | Instagram: @rapackelaw

To Your Success,

Andrew Rapacke

Managing Partner & Registered Patent Attorney

Rapacke Law Group, P.C.