Most people waste hours deciphering patent documents because they make one critical mistake: they read them like research papers, starting at page one and working forward. This approach is backwards—and potentially costly.

With over 18.6 million patents currently in force worldwide (including approximately 3.5 million in the United States alone), misunderstanding patent scope isn’t just an academic concern. U.S. patent infringement lawsuits cost an average of $3 million through trial, and only about a third of patent owners actually prevailed in litigation in 2023. The financial stakes demand a systematic approach to how to read a patent.

The problem isn’t complexity—it’s methodology. Patents follow a rigid legal structure, with each section serving a distinct purpose; yet these documents are notoriously difficult to read, as they combine technical jargon with legal language. But here’s what patent professionals know: as Judge Giles Rich famously stated, “the name of the game is the claim”—meaning the claims section is the most essential part of the patent, as it defines what’s actually protected and sets the boundaries of patent rights.

This guide will show you the proven method patent attorneys and IP professionals use to efficiently extract critical information from any patent document—whether you’re analyzing competitors’ AI patents, evaluating prior art for your SaaS innovation, or conducting due diligence for potential investors.

What you will learn:

- The essential steps for reading patents efficiently and systematically.

- How to navigate the four-part structure of every United States patent.

- How to analyze the front page to assess patent relevance and status quickly.

- Techniques for interpreting patent drawings and their relationship to claims.

- How to extract critical information from the specification and detailed description.

- Methods for decoding patent claims to understand the legal protection scope.

- Practical strategies for using patents in business and research contexts.

How to Read a Patent: Essential Steps

The conventional approach to patent reading—starting with the title and working chronologically—wastes valuable time and often leads to fundamental misunderstandings about what’s actually protected. Patent educators and professionals consistently recommend a claims-first approach as best practice.

Start with the claims section first to understand what the patent actually protects. The claims define the legal boundaries of the invention and determine what would constitute infringement. Importantly, the claims set the scope of the claimed invention, establishing what is protected and the extent of legal coverage. Everything else in the patent document supports and explains these claims. By reading claims first, you can judge the patent’s relevance to your interests before investing time in technical details—critical when you’re racing to market with your software platform or AI-powered tool.

Consider Amazon’s famous one-click checkout patent (U.S. Patent No. 5,960,411, issued 1999). Rather than reading through pages of technical description about e-commerce systems, you can immediately see from Claim 1 that it covers “a method for placing an order to purchase an item via the Internet” with specific requirements for client identifiers and single-action ordering. This broad claim gave Amazon a competitive edge—they even obtained an injunction against Barnes & Noble’s similar “Express Lane” checkout in 1999. Skimming the allegations reveals the scope of Amazon’s legal protection, allowing you to decide if the patent is relevant to your product or research. Most patents include both system and method claims to cover different aspects of the invention, ensuring comprehensive protection for both tangible systems and processes.

Review the front page for basic patent information and filing history. The cover page provides essential context, including the filing date, priority claims, patent classification, inventors, assignee, and cited prior art. This metadata helps you understand the patent’s age, ownership, technological category, and the prior art considered by the patent examiner.

The filing date establishes the cutoff for prior art—anything published after that date generally can’t invalidate the patent. Understanding the costs of obtaining a patent is essential for inventors, as it can affect when and how to pursue protection. The assignee indicates who owned the rights at the time of grant (often a company if the inventors assigned their rights). These front-page details can save you hours when analyzing multiple patents—particularly valuable when mapping the competitive landscape for your technology sector.

Examine the drawings to visualize the components and structure of the invention. Patent drawings aren’t just illustrations—they are formal technical figures that correspond to numbered elements in the text. Scanning the figures gives a quick sense of how the invention works or is constructed. For software and AI patents, flowcharts and system architecture diagrams can reveal the logical structure faster than reading pages of technical specifications. Often, complex systems become much clearer when you see a diagram or flowchart.

Read the specification (written description) to understand technical details and context. The specification provides the background, summary of the invention, and detailed descriptions of embodiments (examples of how to make and use the invention). This is where you’ll find the rationale behind the invention, its improvements over prior technology, and specific examples. Focus on the parts of the spec that relate to the claim elements you identified. The specification must provide sufficient detail so that a person of ordinary skill in the art can make and use the claimed invention, ensuring the enablement requirement is met.

Focus on understanding legal scope, not just technical details. Remember that patents are legal documents first and technical documents second. It’s not enough to know how something works; you must understand precisely what is legally protected and what is not. Keep asking: “If I change this element, would I avoid infringement? Does this description limit the claim’s meaning?” Many patent newcomers get lost in the engineering details and miss that a claim might be much narrower (or broader) than the technical description suggests.

By following these steps—Claims → Front Page → Drawings → Specification**, all with an eye on legal scope—you’ll efficiently extract the most critical information. This approach prevents you from spending hours on a patent, only to realize the claims weren’t relevant to your query.

Patent Document Structure Overview

Every United States utility patent follows the same four-part structure mandated by USPTO regulations. This standardized format ensures consistency and makes it easier to locate specific information once you understand the system:

1. Front Page: Contains bibliographic data and summary information, including the patent number, title, inventors, assignee, filing dates, and abstract. The front page functions like a cover sheet, providing key metadata at a glance. It often also includes one representative drawing, selected by the patent examiner from the set of drawings, to highlight the key features of the invention, as well as a brief abstract of the invention.

2. Drawings: Illustrate the invention’s components or process steps through formal technical drawings. Not all patents include drawings (for example, some purely chemical or mathematical inventions may not); however, most utility patents do so to clarify the invention’s structure or operation. Drawings can include mechanical diagrams, circuit schematics, flowcharts for software methods, or system architecture diagrams—especially common in technology patents. A representative drawing is selected from the provided set and featured on the front page to showcase the invention.

3. Specification: The detailed written description of the invention, which typically has several subsections:

- Field of the Invention: the general technology area.

- Background: problems or prior art that motivated the invention.

- Summary of the Invention: a high-level overview of the inventive solution.

- Detailed Description of Embodiments: thorough disclosure of at least one way to make and use the invention, often referencing the drawings.

- Examples: specific implementations or experimental results (common in chemical/pharma patents).

- Definitions: explicit definitions of terms, if needed.

The specification may reference related prior art and other publications, such as previous patents or academic papers, to establish the novelty of the invention.

The specification must enable a person skilled in the art to make and use the invention without undue experimentation—a legal requirement under 35 U.S.C. §112. The U.S. Supreme Court recently reiterated that “the more one claims, the more one must enable”—broad claims require correspondingly broad disclosure in the spec.

4. Claims: The numbered legal statements at the end of the document that define the scope of patent protection. Each claim is a single sentence, carefully worded to include all the essential elements of the invention that the patentee wishes to protect. Claims can be independent (stand-alone) or dependent (referring back to and adding limitations to a previous claim).

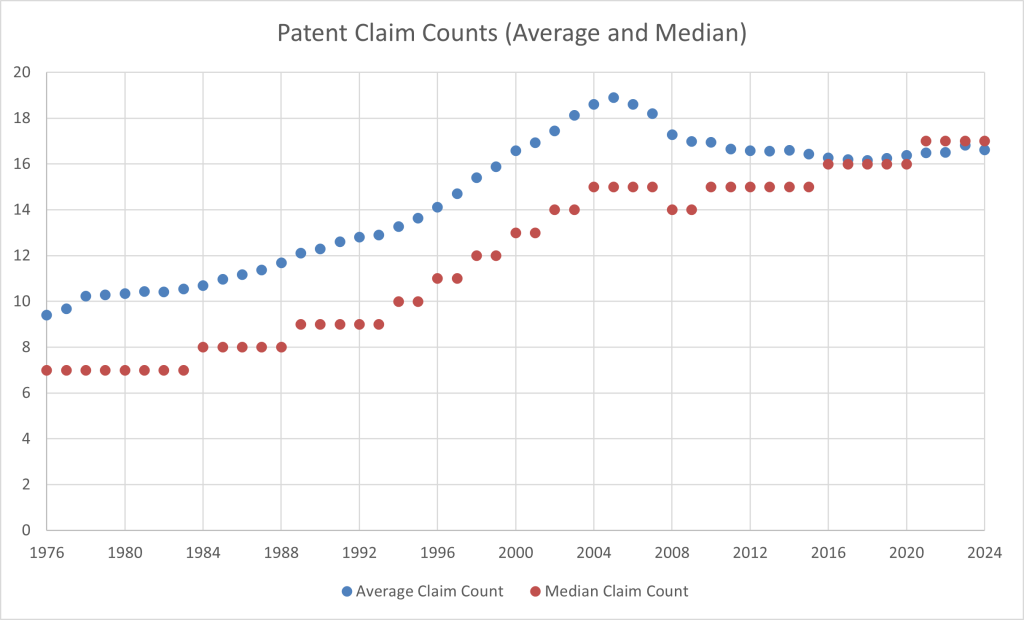

Most issued U.S. patents range from roughly 10 to 50 pages in total length, though complex inventions (like biotech or software algorithms) can be much longer. U.S. patent applications in recent years have approximately 16-17 claims on average, often with 2–3 independent claims and numerous dependent claims that flesh out the specifics.

Figure 1: “Average claim counts in U.S. patents have steadily declined—from nearly 19 claims per patent in 2005 to about 16–17 in 2024—reflecting cost pressures and narrower prosecution strategies (Patently-O, 2024).”

Claims are expensive—the USPTO charges extra fees for more than 20 claims or more than three independent claims—so applicants tend to draft a moderate number that balances coverage with cost.

Understanding this structure helps you navigate efficiently to the information you need:

- If you’re checking for potential infringement, focus on the Claims (and supporting parts of the spec for claim interpretation).

- If you’re researching technical solutions, concentrate on the Detailed Description and Drawings—that’s where the “how to” is.

- If you’re assessing a patent’s validity or looking for prior art, examine the front page references and background to see what the examiner already considered, then scrutinize the claims versus older publications.

- If you’re mapping out a patent landscape, start with the front page for each patent—the title, assignee, and classification will help categorize it, and the filing/priority dates indicate the timeline.

Analyzing the Patent Front Page

The patent front page contains a wealth of information encoded in a standardized format, often using INID codes (small numbers in parentheses) that identify each field internationally. Learning to extract key data from this page quickly can save hours when screening patents or conducting prior art searches.

Title and Abstract

The Title appears near the top and gives a broad idea of the subject matter. Titles are limited to 500 characters and often employ fairly generic terms to comply with USPTO rules. For example, the “Electronic Commerce System” patent for Amazon’s one-click feature provides high-level categorization but usually does not reveal the specific innovation or its novel point.

The Abstract is a concise paragraph (up to 150 words) that summarizes the invention’s main features. It’s intended to provide a brief overview of the patent. However, neither the title nor the abstract defines the legal scope. They are helpful for initial understanding or database searching, but any legal analysis must focus on the claims. Think of the abstract as the back-cover blurb of a book—a helpful summary, but not the whole story.

Amazon’s one-click patent abstract describes an online ordering system in general, but only the claims specify the specific one-click purchase mechanism. Never rely on the abstract alone to determine infringement or validity. Use it as a clue for relevance, then dig deeper.

Inventor and Assignee (Ownership) Information

The Inventors are listed with their cities and states (or countries) of residence. This identifies who actually conceived the invention. In some cases, seeing multiple inventors from diverse locations or a famous inventor’s name can be insightful.

The Assignee field (if present) shows the owner of the patent at the time of issue. Often, this refers to a company or university to which the inventors assign rights. Under U.S. law, inventors initially own their patent rights unless they assign them. In practice, employee-inventors nearly always assign their inventions to their companies.

Ownership can change after issuance via sales or corporate mergers. The front page won’t reflect those changes. To find current ownership, you’d check the USPTO’s Assignment Database. This matters if you need to know who to license from or who might sue for infringement—critical intelligence when you’re building a competitive technology product.

Modern innovation is often collaborative. Patents today frequently have multiple inventors—the average U.S. patent listed 3.2 inventors in 2024, nearly double the average 1.7 inventors in the 1970s. This trend reflects the growing trend of team-based R&D across industry and academia. Don’t be surprised to see five, ten, or more inventors listed on a single patent, especially in complex fields such as biotechnology, semiconductors, or AI/machine learning systems.

Critical Dates (Filing, Priority, Publication, Issue)

Filing Date: The date the patent application was officially filed with the USPTO. This is a crucial legal date. Any public disclosures or prior art after this date generally cannot be used to invalidate the patent (because novelty is assessed as of the filing date). Think of it as the date the inventor staked their claim.

In the U.S., the patent term (20 years for utility patents) is measured from the earliest effective non-provisional filing date (not counting provisional applications). The filing date also allows you to estimate the expiration date (20 years plus any extensions or minus any terminal disclaimers).

Priority Date: Sometimes listed as “Priority Claim” or “Related U.S. Application Data.” This can be earlier than the filing date if the patent is a continuation, divisional, or claims benefit of a provisional or a foreign application. Priority can be a complex chain in cases of continuations. It indicates whether the patent is part of a family and how far back its lineage extends.

Publication Date: For applications filed after November 2000, the USPTO publishes most applications 18 months after the earliest priority date. This is when the application became public.

Issue Date (Publication of Patent): The date the patent was granted (usually near the top of the front page). This is when the patent rights actually became enforceable. Between filing and issue, an application is pending (not enforceable). After the issue is resolved, the owner can sue infringers.

These dates help you calculate the expiration (20 years from the effective filing date). They also set the stage for prior art—anything before the priority date could be considered prior art, whereas anything after is not (for novelty). Amazon’s one-click patent expired in 2017, after which everyone could use one-click checkout freely.

Patent Classification

The front page lists classification codes, typically under headings such as “Int. Cl.” (International Classification) and “U.S. Cl.” (the old US classification, now largely replaced by CPC). The Cooperative Patent Classification (CPC) is now the primary system used by the USPTO and EPO, with over 250,000 subclasses for fine-grained technical topics.

A patent’s CPC codes indicate the general area to which it belongs and help facilitate searches for related patents. If you notice a particular CPC class on a patent of interest, you can search for other patents in that class to discover similar technologies. It’s an advanced technique for thorough prior art searching or landscape analysis—particularly valuable when you’re preparing your own patent application and need to understand the competitive IP landscape.

References Cited (Prior Art)

Every patent lists references (prior art) that were considered during examination. These appear as a list of U.S. Patent Documents, Foreign Patent Documents, and Non-Patent Literature on the front page.

Examiner-cited references (often indicated by an asterisk or a separated list) show what the patent examiner found as the closest prior art. These references are essential, as they reveal what the examiner considered relevant. When evaluating the patent’s strength, consider whether the patent was deemed novel and non-obvious relative to the cited documents.

Applicant-cited references (ones submitted in an Information Disclosure Statement by the applicant) show what the inventor or their attorney knew of the prior art. Often, applicants cite dozens of references (especially in software and biotech cases) to make sure the examiner is aware of them.

Non-Patent Literature (NPL) encompasses scientific papers, articles, web pages, and technical standards, among other sources, that are cited as prior art. Increasingly, patents cite numerous NPLs—one study found that U.S. patents now cite about two scientific articles on average in their front-page references, reflecting how patents build on academic research.

Understanding the costs of obtaining a patent is essential for inventors, as it can affect when and how to pursue protection. If a piece of prior art is listed on the front page, it’s harder to use that same piece to invalidate the patent later. U.S. law presumes that the examiner considered it and allowed the patent to be granted over it. So challengers usually look for uncited prior art.

Front-Page Summary: In just a minute or two, by scanning the front page, you can identify:

- What the invention broadly is (title/abstract).

- Who invented it and who owned it at the time of issuance.

- When it was filed and issued (and thus if it’s still in force).

- Where it fits in the technology classification.

- Which prior art was considered relevant?

This contextual information is invaluable for quickly filtering patents during analysis.

Interpreting Patent Drawings

Patent drawings follow strict formal requirements and are an integral part of the disclosure. U.S. patent rules mandate drawings for any invention that can be illustrated (37 C.F.R. 1.81). Understanding how to read these drawings effectively can dramatically improve comprehension of complex inventions. The primary purpose of these drawings is to illustrate the core aspects of the patented invention, making clear what is protected under the patent. Any prior art drawings included serve only as background and do not represent the patented invention itself.

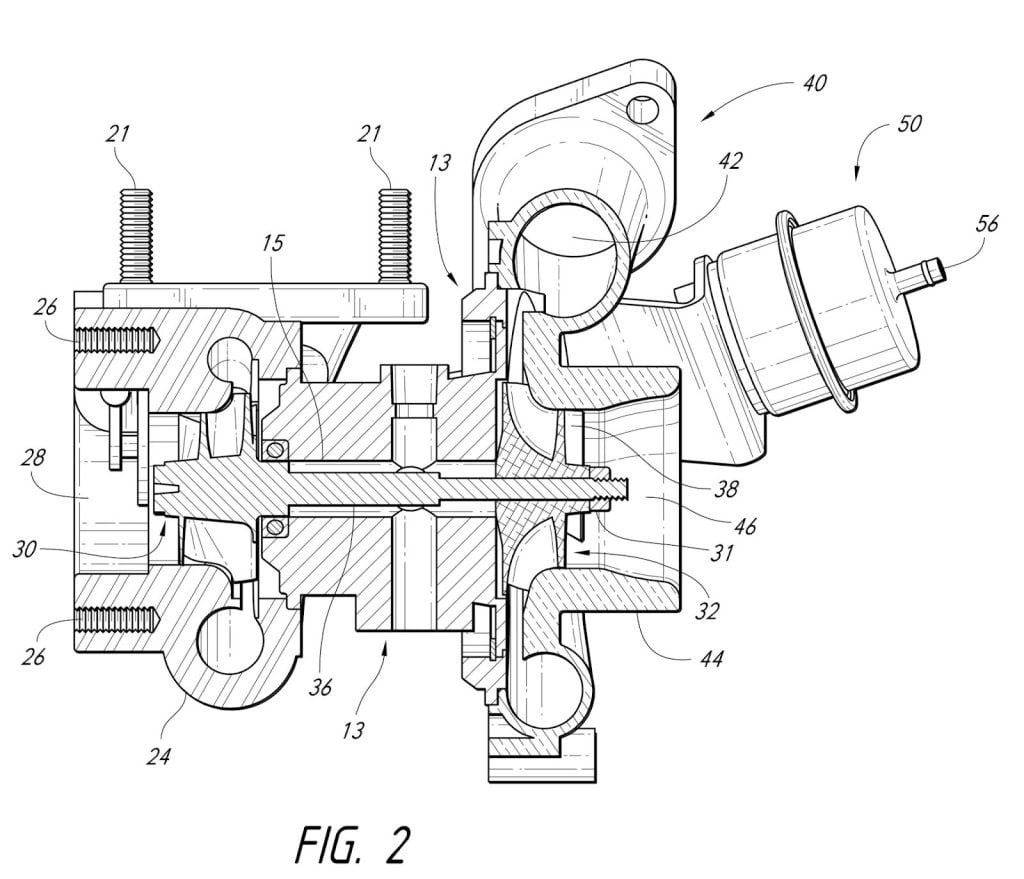

Figure 2: “Mechanical patent drawing (exploded view) with reference numerals identifying components of the assembly (e.g., parts 24, 31, 36, 42).” Source: USPTO.

Drawings Are Often Required: Mechanical and electrical inventions almost always have diagrams. Software or business method patents often include flowcharts or block diagrams to illustrate their concepts. Only if an invention can be fully described in words (or if drawings are impractical) will you see no drawings.

Figure 1 = Big Picture: Figure 1 in a patent is usually a view of the overall system or device—the preferred embodiment in its entirety. It provides a high-level overview of how components interact and fit together. Later figures (Fig. 2, 3, etc.) then zoom in on details or alternative views.

Multiple Views and Exploded Diagrams: Patents often feature multiple views (front, side, cut-away) or exploded diagrams that show parts disassembled. These help you visualize internal relationships and assembly. Exploded views are especially helpful in mechanical patents to understand how the pieces fit together.

Flowcharts for Methods: In method patents (standard in software or processes), you may see flowcharts or schematic diagrams instead of physical parts. Each box in a flowchart typically corresponds to a step in a method claim. By following the flowchart, you can visualize the process’s logical flow, which is significant for understanding AI algorithms, machine learning training methods, and SaaS platform architectures.

Reference Numbers: This is key. Every element in a drawing is labeled with a reference number, and that number is used in the specification to describe it. For example, a patent drawing might label a component as (10), and in the text you’ll find “The widget (10) is connected to the frame (20) via hinge (15)…”

According to USPTO guidelines, every feature of the invention that is specified in a claim must be shown in the drawings, and reference numerals in the drawings should correspond to the written description. If something is claimed, you should find it labeled in at least one figure.

Reading Drawings with the Spec: A great strategy is to identify a few key reference numbers in the central figure and then search the text for them. This ties the narrative to the image, often clarifying the part’s role.

Understanding Patent Drawing Conventions: Patent drawings are usually black-and-white line drawings. They follow conventions like:

- Lead lines: thin lines connecting reference numbers to the parts.

- Sections and cutaways: often indicated by cross-hatching.

- Flowchart symbols: diamonds for decisions, rectangles for steps.

- Electric circuits: standard circuit symbols for resistors, transistors, etc.

Use the drawings to your advantage: If a patent’s text is dense, flipping to the drawings can provide an “aha” moment of clarity. Drawings can reveal embodiments not explicitly spelled out in words. By correlating figures and text, you ensure you truly understand the invention in 3D or in flow, not just as abstract words.

Reading the Patent Specification

The Specification is the heart of the patent document’s technical disclosure. It’s where the inventor tells the story of the invention: what it is, why it’s needed, how it works, and how to use it. The spec must satisfy legal requirements of enablement and written description (meaning it must fully support the claims).

Background and Field of Invention

The spec often begins with the Field of the Invention, a one-liner stating the general area (e.g., “The present invention relates to machine learning systems, and more particularly to natural language processing algorithms.”). This is useful for orienting yourself and verifying you’re in the right domain.

The Background section usually outlines the problem or deficiency in prior technology that the invention addresses. It might describe conventional solutions and their drawbacks, as well as any unmet needs. The background often describes the technical problem the invention solves and how it overcomes challenges present in prior art. By reading this, you understand why the inventors did what they did. It sets up a narrative: “Here’s what others did and why it’s not sufficient; thus our invention.”

Caution: Statements in the background can sometimes be used against the patentee as admissions of prior art or to define the scope of the problem. However, as a reader, it provides great context. If you’re doing competitive analysis, the background can hint at what the inventors knew and considered as of their filing date.

Summary of the Invention

Not every patent has a labeled “Summary,” but many do. This section provides a high-level overview of the inventive concept and key features. It often reads like a broader version of the claims (sometimes literally a paraphrase of the independent claim in plain English). The summary might highlight advantages.

For a quick grasp, the summary is golden—it’s usually easier to read than the claims, but more specific than the abstract. However, legally, the summary is not the claims. A patent may describe numerous desirable features in summary or elsewhere that do not ultimately end up in the claims. So, use it to understand context, but always circle back to what’s actually claimed.

Brief Description of Drawings

A list of figures: “Fig.1 is a schematic of X; Fig.2 is a flowchart of Y; …”. This isn’t conceptual content, but it’s helpful to skim so you know what figures exist and what they represent.

Detailed Description of Embodiments

This is the longest part. It’s where the inventor walks through examples of how to make and use the invention, often referencing the drawings. This section must enable the invention, meaning someone skilled in the art could implement it after reading.

Look for concrete examples and preferred embodiments. For instance, in the case of artificial intelligence patents, the inventor will describe at least one preferred way (the “best mode” if the application was filed before 2013). This is typically the commercially most relevant form of the invention.

Alternative embodiments and variations: The spec often says things like “In another embodiment, the widget may be made of aluminum instead of steel,” or “Figure 3 illustrates an alternate configuration lacking the lever…” These broaden the disclosure and demonstrate that the inventor considered various forms.

Examples (if any): In fields like chemistry or biotech, you might see specific examples or experimental results. These demonstrate operability and provide support for ranges.

Definitions: Sometimes the specification includes a paragraph that defines the specific terms used in the patent. Pay attention to these—they can override common meanings. If the patent defines a term, that definition typically controls how the claims are interpreted.

In the 2023 Amgen v. Sanofi case, the Supreme Court invalidated broad antibody claims that weren’t fully enabled by the spec. Assess whether the spec seems highly detailed or pretty high-level. If it’s very high-level and you, as a person skilled in the art, have doubts about being able to reproduce the invention, that could indicate a potential enablement issue.

Why the Specification Matters Legally

During litigation, courts often read the spec to interpret ambiguous claim terms (this is called claim construction or a Markman hearing). If a term isn’t clear, they see how the inventor used it in the spec. The spec can limit claims through disclaimers. If the inventor disparages a specific prior art approach in the background, then claims broadly, a court might infer the claim doesn’t cover that disclaimed approach.

In practical reading, don’t try to memorize the whole spec. (For those interested in patenting AI inventions, see this comprehensive guide on patents for artificial intelligence.) Instead:

- Gain a general understanding of the problem and its solution.

- Pick out definitions or critical features.

- Ensure you know how the leading example works.

- Use headings (if provided) to jump around.

By the end of reading the spec, you should be able to explain in your own words:

- What the invention is and how it works.

- What problem it solved, and how it’s different from prior art.

- Variations or alternatives, the inventor mentioned.

- Any special meanings of terms?

Decoding Patent Claims

The Claims section is the most critical part of the patent for legal purposes—it defines the patent owner’s rights. Each claim is like a checklist of features; if someone’s product or process has every feature of a claim, then it infringes that claim (assuming the patent is in force). If even one feature is missing or different, it does not infringe that claim.

Reading claims is an art in itself. They are written in a single sentence, often with awkward, legalistic phrasing, punctuation, and plenty of “patentese” (such as “comprising”, “wherein”, etc.). But mastering claim interpretation is essential—it’s the difference between confidently building your technology and unknowingly stepping into an infringement minefield.

Independent vs. Dependent Claims

Independent Claims stand on their own and do not reference any other claim. They are typically the broadest claims. In a patent, Claim 1 is almost always independent, and there may be a few more independent claims scattered (like Claim 10, 20, etc.). If you are seeking professional guidance on patent law, consider consulting Andrew Rapacke, a registered patent attorney.

Dependent Claims refer back to a previous claim and add one or more limitations. For example, Claim 2 might start, “The method of claim 1, wherein the user is authenticated via a biometric identifier.” That means Claim 2 includes all the elements of Claim 1, plus the additional biometric feature. Dependent claims thus narrow the scope.

Dependent claims are easy to spot: they’ll say “The [device/method] of claim X, wherein/whereby/further …”.

Why have dependent claims? They serve as fall-backs. If claim 1 is later found invalid (too broad), claim 2 (narrower) is still valid. They also carve out specific embodiments or preferences. From a reading perspective, always read the introductions first. They give the broad picture. Then see what the dependents add.

Patents often have multiple independent claims of different types (e.g., one apparatus claim, one method claim, one computer-readable medium claim covering software)—a common strategy in software and SaaS patents to maximize protection angles.

Claim Structure and Wording

A claim generally has a preamble, a transition word, and a body:

Preamble: Introductory phrase naming the category of the invention and its intended use or context. E.g., “A method for processing digital images, comprising: …” or “An apparatus for dispensing coffee, comprising: …”. The preamble can sometimes be ignored in infringement analysis unless it states something essential.

Transition Word: This is crucial—it’s the word that links the preamble to the body and indicates whether the claim is open or closed:

- “Comprising” means including, but not limited to. This is an open-ended transition. If a claim says “comprising A, B, and C,” an accused product that has A, B, C, and additional elements D and E can still infringe. Comprising = at least the listed elements are present. This is the most common and gives broad coverage.

- “Consisting of” means limited to exactly these elements and no more. A claim “consisting of A, B, and C” would not cover something that has A, B, C, and D.

- “Consisting essentially of” is in between. It allows additional elements that do not materially affect the basic operation or novel characteristics.

Body: The meat of the claim—a list of elements or steps, usually set out as a list of clauses separated by semicolons. Each clause often begins with a noun phrase and then describes its relationship or function.

Interpreting a Claim

Break it down into elements (also called limitations). Identify each “and” or step as a separate requirement.

Every limitation is required for infringement. If a competitor’s product lacks one limitation, it doesn’t infringe that claim. Likewise, to invalidate a claim with prior art, a single prior art reference must disclose every limitation (for anticipation) or a combination must render every limitation obvious.

As you read each limitation, try to map it to something in the real world or in the spec’s embodiment. Pay attention to punctuation and words like “wherein” and “said”.

Order of steps (for method claims): Unless the claim explicitly or implicitly requires a sequence, method steps might not need to be performed in the listed order. However, context or logic often imposes an order.

Means-plus-function: If you see a claim element like “means for [doing X]”, that’s a special type of claim (means-plus-function under §112(f)). It doesn’t prescribe a specific structure; instead, it prescribes a function. Legally, it covers the structures described in the spec that perform that function (and equivalents).

Claim Types

- Apparatus or Device Claims: These claims pertain to a physical object. Infringement occurs by making, using, selling, offering to sell, or importing the claimed device.

- Method or Process Claims: These claims describe steps to accomplish something. Infringement occurs when all the steps are performed.

- Computer-Readable Medium (CRM) Claims: Common in software patents—claims a storage medium with instructions that cause a processor to do X, Y, Z.

- Composition of Matter Claims: In chemistry, claiming a compound or material.

Reading Strategy for Claims

- Identify all independent claims. Read each thoroughly.

- For each independent, read its dependents in order.

- If the patent has different independent claim categories (e.g., system and method), treat them separately.

- Don’t neglect the last few claims—sometimes a vital feature is only claimed at the end.

- Make a quick outline or table: list the elements of each independent claim.

Legal Scope vs Technical Description

The claims may be much narrower than what’s described in the spec. Inventors often describe broader concepts, but during prosecution, they must narrow claims to avoid prior art. Always refer to the claim language for what’s protected, not the general tone of the description.

Key Takeaway: A patent is only infringed if the accused product/process meets every single requirement of at least one claim. Conversely, a patent claim is invalid if any single prior art reference shows every element (or a combination would have made it obvious). This “all elements” rule is why each word in a claim can be outcome-determinative.

Practical Patent Analysis Strategies

Reading a single patent is one thing; often, your task will involve analyzing multiple patents or leveraging patent information for a broader purpose. Here are practical strategies that professionals use to efficiently and effectively analyze patents:

Claims-First, Always: When you have a stack of patents, read the claims (especially independent claims) first on each to triage relevance. It’s common to discover that 50% of them are not relevant to your specific question after just a quick skim of the claim.

Compare within Patent Families: Many inventions give rise to a family of related patents, including continuations, divisionals, and foreign counterparts. If you find one patent of interest, check if it has family members. The family might have broader or additional claims. Companies often file multiple applications to get different claim scopes—a strategy we frequently employ for our SaaS and AI clients to maximize protection across different product implementations.

Patent Landscape and Competitor Analysis: If you’re examining a field, create a simple matrix or summary for each patent:

- Key features in claims.

- Assignee (owner).

- Filing/priority date (timeline).

- Status (active/expired).

- Any notable cited references.

Tracking inventor or assignee names is also revealing. If an engineer appears on multiple patents, they’re likely a key expert. If a competitor suddenly files numerous applications in a new area, that signals a strategic move.

Use Classification and Keywords Smartly: For prior art search or discovering related patents, use the Cooperative Patent Classification (CPC) codes from a known relevant patent to find others in the same subclass. Because CPC is very granular, this often yields more precise results than keywords alone.

Patent Status Check: Not all patents remain in force for their full term. In fact, many U.S. patents expire early due to non-payment of maintenance fees (due at 3.5, 7.5, 11.5 years after grant). Globally, approximately 17.5% of patents last the full 20-year term; many lapse once they become less valuable. Before worrying about a patent, check its legal status. The USPTO Patent Center or status lookup can tell you if it’s active or expired.

Prosecution History (File Wrapper): For in-depth analysis (especially legal), reviewing the patent’s file history can provide valuable insights. The file history contains all correspondence between the applicant and the patent office, including rejections, arguments, and amendments. This can reveal:

- Why were the claims changed (perhaps to overcome certain prior art)?

- Any arguments or definitions made by the applicant that can limit claim interpretation.

- If you suspect a claim term is ambiguous, the file history might clarify what both sides understood it to mean.

Accessing file wrappers is easy for U.S. patents via USPTO’s PAIR or Patent Center, or services like Google Patents.

Consult a Patent Attorney for Complex Issues: If your purpose is to assess infringement risk or validity challenges, a patent attorney or agent should be involved. They are trained in the fine points of claim interpretation and legal standards. While you can conduct extensive technical analysis, certain pitfalls are legal landmines. Working with experienced counsel—particularly those specializing in tech IP—can save you from costly mistakes and help you develop strategic patent portfolios that actually protect your innovation.

Focus on Independent Claims for FTO (Freedom to Operate): When designing around, ensure your product omits or changes at least one element from every independent claim of a relevant patent. Since dependent claims include all of the independent claim’s elements, by avoiding the independent claim, you automatically avoid all its dependents.

Evaluate Patent Value/Strength: Consider:

- Claim Breadth vs Prior Art: Does the patent claim something fundamental or a narrow improvement?

- Number of Claims and Redundancy: A strong patent typically has multiple layers of claims that cover an invention in different ways.

- Cited Prior Art: If the examiner cited very close prior art, the patent may have had to be narrowed to be granted.

- Industry adoption: Is the patented tech core to an industry standard or widely needed?

- Remaining Life: A patent with 1 year left is less threatening than one with 10 years left.

Keep Notes and Summaries: When reviewing multiple patents, maintain a spreadsheet or document to record key points. Include the source (patent number), a one-line summary in plain English, notable claim features, and any concerns or ideas.

Integrate Patent Info with R&D Decisions: Patents are a rich source of technical and competitive intelligence:

- Technical: They reveal what solutions are known or preferred. An estimated 70–80% of technical information in patents might not be published elsewhere.

- Competitive: They reveal who is innovating in what space and sometimes why.

Ethical/Legal Considerations: Some companies debate whether engineers should read patents due to concerns about willful infringement (knowing about a patent and infringing it can expose one to higher damages). Company policies differ. Always follow your legal counsel’s guidance on this point.

Stay Current: Patent landscapes can change—new patents issue, old ones expire, some get invalidated in court or through IPR (inter partes review). It’s good practice to periodically update searches in fast-moving fields, especially in rapidly evolving technology sectors such as AI, machine learning, and SaaS platforms, where the patent landscape shifts every month.

Key Takeaways

Patents follow a standardized structure (front page, drawings, specification, claims) that enables systematic analysis once you understand the format and purpose of each section. For example, jump to the scope claims, use the spec to clarify technical details, and glean context from the front page.

Claims define the legal scope of protection—always start with claims to see what’s actually covered. Don’t be misled by titles or abstracts; only a claim’s wording delineates infringement or validity. As the saying goes, the name of the game is the claim.

The front page contains essential metadata, including the inventor and assignee (who’s behind the patent), filing/priority dates (to assess novelty and expiration), classification (technical field code), and references (key prior art). These give crucial context at a glance. For instance, the assignee tells you who might enforce the patent, and the references tell you the tech lineage and can jump-start a prior art search.

Patent drawings are powerful tools for understanding complex concepts. They correspond directly to elements in the spec (reference numbers linking images to text) and can clarify complex concepts more effectively than paragraphs of description. Always correlate figures with the written description to get a complete picture. A well-drafted figure can make the “aha” difference in grasping an invention’s design or method flow.

The specification provides the technical deep dive needed to enable the invention. It’s where you learn the how and why. Use it to interpret claims correctly (pay attention to any definitions or consistent embodiments). Remember, what’s disclosed in the spec but not claimed is not protected—but it might still be practical know-how or could appear in future claims via continuations.

Practical patent analysis requires a strategic approach. Don’t treat a patent in isolation if you’re addressing a broader question:

- Review related patents and applications (including family and citation networks).

- Monitor the patent’s legal status (i.e., whether it is in force, licensed, or litigated).

- Compare across competitors to identify overlaps and gaps in their offerings.

- Keep the end goal in mind: Are you searching for design-around options? Assessing if you infringe? Gauging a technology’s landscape?

Patents are business and legal tools, not just technical documents. A patent you read could represent years of R&D investment, and companies leverage them strategically for competitive advantage — blocking competitors, enabling cross-licensing, and strengthening their market position. Before a provisional patent is filed, prudent companies often use patent non-disclosure agreements (NDAs) to protect intellectual property during early discussions — whether pitching ideas to investors, collaborating with partners, or sharing concepts internally among employees. One analysis estimated that a modern smartphone is covered by approximately 250,000 patents, illustrating the dense web of IP (“patent thickets”) surrounding complex products. This underscores why savvy companies rigorously manage confidentiality and navigate the patent landscape when bringing innovations to market.

Continuous learning: The more you read and even write patents, the better you’ll understand them. Initially, you may find them cumbersome, but persevere. Try reading some patents in your field of expertise first—you’ll have the context to decode them. Over time, you will develop an intuition for spotting key claim phrases, recognizing what differentiates an invention, and even predicting how an examiner or court might view a patent.

Your Next Steps to Patent Analysis Success

Understanding how to read patents is just the beginning. Whether you’re analyzing competitors’ IP portfolios, conducting freedom-to-operate research, or preparing to file your own patent application, the ability to decode patent documents efficiently gives you a critical competitive advantage. It can help avoid inadvertent infringement, saving potentially millions in litigation costs (which, as noted, average around $3M through trial in the U.S.).

The bottom line: Reading patents isn’t just an academic exercise—it’s strategic intelligence gathering. Companies that understand the patent landscape make better R&D decisions, avoid costly legal battles, and identify opportunities for innovation in white spaces. Those that don’t often find themselves either infringing unknowingly or missing opportunities to protect their own innovations effectively. With RLG’s fixed-fee model and The RLG Guarantee backing your IP strategy, you gain the confidence that comes from experienced patent prosecution. Whether you’re building an AI platform, launching a SaaS product, or developing hardware innovations, weak or nonexistent patent analysis leaves you vulnerable while competitors fortify their market positions.

Here’s the reality: Every day you delay conducting proper patent analysis is another day your competitors might be filing patents that block your path to market. In a first-to-file system, timing is critical. Meanwhile, you’re developing technology without understanding the existing patent landscape. In that case, you could be building on ground someone else already claimed—a mistake that could cost you your entire product, not just money. The technology companies that dominate their markets don’t just build great products; they understand the IP landscape and protect their innovations strategically.

Take these immediate action steps:

- Schedule a Free IP Strategy Call to discuss how to leverage your patent analysis findings in your competitive strategy, whether you’re conducting freedom-to-operate research, evaluating competitors’ patents, or preparing your own filing strategy.

- Download our comprehensive resources to deepen your understanding of patent strategy:

- AI Patent Mastery Guide for AI and machine learning innovations.

- SaaS Patent Guide 2.0 for software and platform protection strategies.

- Conduct a preliminary landscape analysis in your technology area using the techniques outlined in this guide—start with CPC classification searches and analyze your top three competitors’ patent portfolios.

- Identify patents that could impact your product roadmap and document your analysis for review with qualified patent counsel.

Looking forward: The patent landscape in technology sectors is becoming increasingly complex, with AI-related patent applications growing exponentially year over year. Whether you’re protecting novel machine learning algorithms, innovative SaaS architectures, or breakthrough hardware designs, understanding how to read and analyze patents is foundational to building a defensible competitive position. The investment you make in developing these skills—or working with experienced patent counsel who can guide you—pays dividends through avoided conflicts, strategic filing decisions, and ultimately, stronger IP portfolios that attract investors and deter competitors.

Intelligent patent analysis today prevents costly problems tomorrow. Don’t let patent literacy gaps undermine your innovation strategy.

The RLG Guarantee: The Patentability Search is the gateway to the patent process. If we conduct the patentability search and find that your invention is not novel, we’ll issue a 100% refund.*

About the Author

Andrew Rapacke is a Managing Partner and Registered Patent Attorney at Rapacke Law Group, specializing in patent protection for AI, software, and SaaS innovations. With extensive experience helping tech startups and established companies navigate complex IP landscapes, Andrew takes a practical, business-focused approach to patent strategy.

Connect with Andrew: LinkedIn | @rapackelaw on Twitter/X | @rapackelaw on Instagram

To Your Success,

Andrew Rapacke, Esq.

Managing Partner, Registered Patent Attorney

Rapacke Law Group