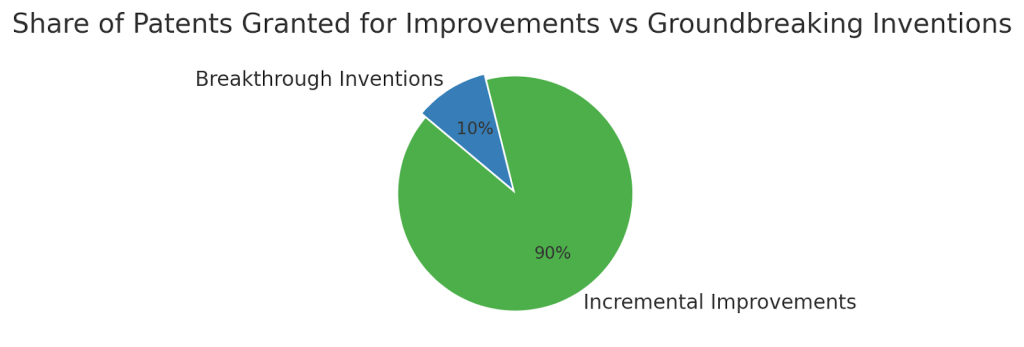

Most patents granted each year protect incremental improvements rather than entirely new inventions. In fact, industry experts estimate that up to 90% of patents granted today cover enhancements to existing technology, from Gillette adding a third blade to razors to Amazon streamlining checkout into one click. If you’ve refined an existing product, your improvement may be more valuable than you think.

The answer to the question: can you patent something that already exists, is yes. Yes, if your improvement meets three specific criteria. Your enhancement must be novel (never publicly disclosed before in this particular form), useful (providing tangible benefit), and non-obvious (not a predictable change to someone skilled in the field). These requirements, defined in 35 U.S.C. §§ 101-103, ensure patents reward genuine innovation, not trivial tweaks.

The answer to whether you can patent something that already exists is complex: While you cannot patent the existing item itself, you can patent a new and inventive improvement to it. This improvement must meet three specific criteria: it must be novel (never publicly disclosed before in this particular form), useful (providing a tangible benefit), and non-obvious (not a predictable change to someone skilled in the field). These requirements, defined in 35 U.S.C. §§ 101-103, ensure patents reward genuine innovation, not trivial tweaks.

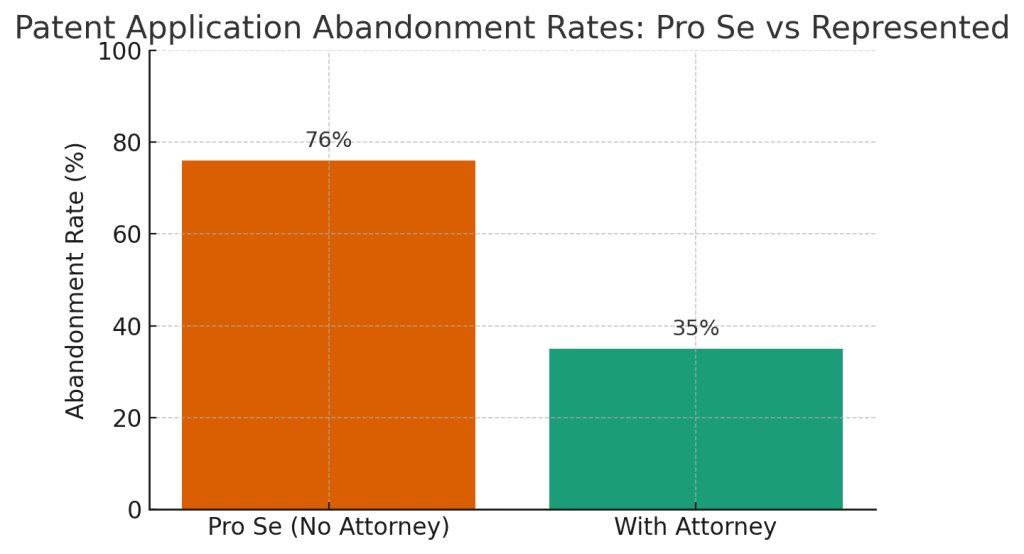

Here’s what matters: The USPTO receives over 600,000 patent applications annually, so understanding how to position your improvement against this competitive backdrop is crucial. This guide breaks down what qualifies as a patentable improvement, how to navigate the prior art landscape, and the strategic decisions that separate successful applications from the 76% of self-filed patents that end up abandoned.

Can You Patent Something That Already Exists? – Key Takeaways

Improvement Patents Dominate Modern Innovation: Even minor enhancements can be patented if they meet the criteria of novelty, usefulness, and non-obviousness. The majority of patents granted each year protect incremental improvements rather than entirely new inventions. Your idea, building on an existing product, could be patentable if it offers a unique advantage.

Figure 1: Roughly 90% of patent grants are for incremental improvements (green) rather than entirely new, “breakthrough” inventions (blue). Innovation typically builds on prior art, which is why U.S. patent law explicitly allows patents for improvements to existing products.

Thorough Prior Art Search is Essential: Before filing, conduct a patent search and research existing patents and publications to ensure your improvement hasn’t already been disclosed. The USPTO receives over 600,000 patent applications annually, so a diligent prior art search improves your odds of standing out and prevents rejections for lack of novelty.

Strategic Filing Approach: Understanding the differences between provisional and non-provisional patent applications is critical. A provisional application offers a cost-effective way to secure an early filing date and “patent pending” status for 12 months, while a non-provisional application undergoes full examination and can lead to an issued patent by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). This flexibility allows you to refine your invention and raise funds before committing to the whole patent process.

Understanding Patentability of Existing Products

To patent an improvement on an existing product, your innovation must clear the same rigorous bar as any other invention. The three requirements work together as filters; let’s discuss each one:

Novelty means your improvement introduces something genuinely new that hasn’t been publicly disclosed anywhere in the world. Adding a feature that already exists in another product, even in a different industry or country, would fail this test.

Utility requires practical benefit. Your improvement must address a real problem or measurably enhance performance. A significant portion of new patents granted each year are for improvements on existing products, from enhancing manufacturing processes to adding AI-powered features to SaaS platforms that dramatically improve the user experience.

Non-obviousness presents the highest barrier. The vast majority of patent applications receive initial rejections based on obviousness. Patent examiners will ask: Would someone skilled in your field consider this a predictable next step? Even adding a fourth blade to a three-blade razor required Gillette to demonstrate why this wasn’t an obvious progression.

Consider the data: In FY 2024, the USPTO received approximately 466,000 UPR (Utility, Plant, Reissue) applications but granted only 327,000 UPR patents. Not every application succeeds, but many successful patents protect incremental improvements rather than groundbreaking discoveries.

The Critical Limitation: Patenting an improvement doesn’t give you rights to the original product. Your patent only lets you exclude others from using your improved version, not the underlying technology. If the original invention is patented and still in force, you could infringe that patent by making or selling your improved product.

Here’s how this plays out: Imagine an existing patent covers a three-legged chair. If you invent a more stable four-legged chair, you might patent the four-legged improvement, but you’d still need permission (a license) from the three-legged chair’s patent owner to legally produce your chair, because it uses the core patented design. This “blocking patent” scenario means the original patent blocks use of the base technology, and your improvement patent blocks others from using the specific improvement. Companies often cross-license or wait for the original patent to expire.

Working with experienced patent counsel who understands improvement patents can help you evaluate prior art and craft arguments emphasizing what’s new and non-obvious about your idea. Our team has helped countless tech founders navigate this complexity, ensuring you only pursue patents where you have a legitimate, defensible innovation. Thorough research and expert guidance are crucial in navigating this, ensuring you only pursue a patent if you have a legitimate innovation that isn’t already in the public domain.

What Qualifies as an Improvement?

The USPTO recognizes various categories of patentable improvements. To be eligible for an improvement patent, your invention must offer a significant enhancement over prior products, though “significant” doesn’t necessarily mean huge. Even incremental improvements can have a substantial impact and thus be patentable, provided they offer some new benefit or functionality that wasn’t available before.

Addition Invention: Introducing New Components

You introduce a new element that wasn’t present in the original product, improving its performance or utility. Gillette’s Mach3 razor introduced a third blade to its previously two-bladed design; that extra blade provided a closer shave and earned a patent, despite razors with multiple blades already existing. Similarly, adding machine learning-based predictive analytics to a traditional CRM system could be a patentable improvement if implemented in a novel way that solves specific customer pain points.

Substitution Invention: Replacing with Better Elements

You replace one part of a known device or process with a different component that yields superior results. Amazon’s “One-Click” checkout essentially replaced the multi-step online shopping cart process with a single-click purchase process. By streamlining an existing system, Amazon created an improvement so unique that it was patented, giving it a market advantage until the patent expired. For SaaS founders, this might mean replacing manual data entry workflows with AI-powered automation that achieves the same result more efficiently.

New Use Invention: Novel Applications

You discover that an existing product can solve a different problem in a novel way. The drug Viagra was originally developed for heart conditions, but researchers unexpectedly found it treated erectile dysfunction, leading to a hugely successful new use patent. Post-it Notes originated from finding a use for a “failed” low-tack adhesive as a repositionable note, transforming a previously useless glue into a billion-dollar invention. In software, this could mean discovering that an algorithm designed for image recognition also excels at fraud detection.

Combination Invention: Integrating New Technology

You combine an existing device with emerging technology to dramatically enhance its capabilities. Adding AI-based image recognition to a home security camera system or integrating blockchain verification into a supply chain management platform can be patentable if it solves problems in a novel way and is not an obvious combination. For more on protecting AI-powered innovations, check out our AI Patent Mastery guide.

Improvement patents often protect enhancements that make existing technologies more efficient, reliable, or convenient to use. A large share of patents each year are for these kinds of incremental improvements, demonstrating that building on existing knowledge is the norm in innovation.

Critical Note: If the base product is patented, your improvement patent does not give you the right to use the base product, only to exclude others from your specific improvement. You may need to license the original patent or wait for it to expire. But your improvement patent means competitors cannot copy your enhancement without your permission, often leading to cross-licensing deals where inventors and companies share rights for mutual benefit.

Non-Obviousness Requirement for Patents

The non-obviousness requirement is often the toughest hurdle for patent improvement patents. Even if your idea is new, you must show that it wouldn’t have been obvious to a skilled person in the field. Obviousness is the primary reason patent applications are rejected; the vast majority of U.S. patent applications are initially rejected as obvious during the first examination.

Examiners will cite prior patents and argue your improvement could have been readily inferred by combining those references. To overcome this challenge, you need to demonstrate what’s special and non-intuitive about your idea:

Highlight Unexpected Results: Did your improvement achieve something surprising or solve a problem others couldn’t? If adding a third razor blade unexpectedly reduced skin irritation while shaving, that evidence of non-obviousness suggests the result wasn’t predictable until it was tried. For software innovations, this might mean demonstrating that your algorithm achieves 50% faster processing speeds through a non-obvious architectural approach (see the criteria for patentability for more details).

Show Complex Combination Requirements: If your invention only becomes obvious by picking pieces from different sources with hindsight, that strengthens your case. You need to demonstrate that no one had the motivation to make that specific combination in the way you did.

Leverage Secondary Considerations: In patent law, commercial success, solving a long-felt but unmet need, or cases where others in the industry failed to achieve the improvement, can support non-obviousness. If experts tried for years to improve a device in a certain way and your idea finally succeeds, that suggests it wasn’t obvious.

The 2007 Supreme Court decision in KSR v. Teleflex made it easier for examiners to reject patents for obviousness by applying “common sense.” The Court said that inventions that combine familiar elements with predictable results are likely to be considered obvious. Since KSR, patent applicants must be prepared with clear reasoning and evidence to demonstrate why their combination isn’t merely a predictable next step.

Practical Strategy: Ensure your patent application clearly highlights what is unconventional about your improvement. Instead of saying “added a filter to a coffee maker,” explain how the filter is made of a novel bio-material that unexpectedly improves flavor extraction, something not suggested in any prior art. By explicitly addressing potential obviousness arguments in your filing with data or examples, you set yourself up for a stronger case.

If you receive an obviousness rejection, don’t panic. These are very common. With skilled patent counsel, applicants often overcome these by adjusting claim scope or providing counterarguments. It may take a few rounds, but many applications ultimately get allowed after clarifying the inventive aspects.

Conducting a Prior Art Search

Before investing in a patent application, conducting a prior art search is critical. Prior art refers to any existing knowledge that’s publicly available before your invention’s effective filing date; this includes earlier patents, published patent applications, journal articles, books, websites, products on sale, etc. If your improvement has already been described or shown by someone else, it cannot be patented due to a lack of novelty.

Why a Thorough Search Matters

Avoiding Rejection: The number one cause of patent rejection is prior art that makes the invention not new or obvious. Discovering such references before you file lets you modify your approach or abandon an unpatentable idea early. As one guide notes, “the purpose of a prior art search is to unearth all pre-disclosed information” relevant to patentability. You want to see what the patent examiner will see when they search so that you can preempt any issues.

Sharpening Your Claims: By examining what’s already out there, you can better define the novel features of your invention. Knowing the closest prior art allows you to craft claims that clearly distinguish your improvement, and can guide your R&D. You’ll tweak your design to avoid overlap with a competitor’s patent.

Infringement Risk Assessment: If your improvement might overlap with someone else’s patent, you need to know that. A search can identify patents in the same field or area of interest. You might discover that an aspect of the base product is patented by another company, requiring licensing or designing around that existing patent.

How to Conduct the Search

Start with free tools like the USPTO Patent Public Search or Google Patents. Search by keywords related to your improvement and by classification codes for the relevant field. Look at both patent literature and non-patent literature (technical papers, product manuals, etc.).

Professional Assistance: It’s often wise to work with experienced patent counsel for this task. They know where to look and how to interpret results, performing exhaustive searches across global databases that can be invaluable in complex fields, especially for software and AI innovations where prior art can be scattered across academic papers, open-source repositories, and international filings.

Document Everything: If you find something very close, analyze if it’s truly the same or if differences remain. Note the dates. Any publication before your invention date counts as prior art. Review the claims of patents you find, not just titles and abstracts. The claims define the patented scope, and your invention might be novel over the claims even if the overall description sounds similar.

Iterative Process: Patent searching is an iterative process. You might uncover one patent that leads you to related patents through the same inventor or citations. Follow those trails, as patent examiners often use cited references to find more art.

Disclosure Requirement: If you proceed with filing, disclose the prior art you found to the USPTO via an Information Disclosure Statement. This is required for known relevant art and ensures the examiner considers it, showing good faith and protecting your patent later.

A diligent prior art search validates that your improvement is novel, helps you frame the application to highlight differences, and flags any legal risks. Given the massive volume of existing patents and publications worldwide, invest the time upfront to research and save yourself headaches later.

Filing a Patent Application for Improvements

Once you’ve determined your improvement is novel and non-obvious, filing the patent application involves several critical steps:

1. Clearly Describe the Base Product and the Improvement

Include context about the original product or process you’re improving. Then make it very clear how your invention enhances or differs from that base. For example, if you improved a lawnmower to make it quieter, describe the conventional lawnmower first, then detail your noise-reduction mechanism. A successful improvement patent application frames the problem and explains how the improvement addresses it in a novel way..

2. Emphasize Specific Problems Addressed

Patent examiners look for why the improvement is meaningful. State explicitly what problem or need your improvement meets that wasn’t met before. For instance: “Existing solar panels lose efficiency when dirty; the improvement is an automated cleaning system that restores efficiency without manual intervention.” If you have data or test results showing benefits (e.g., “our new process is 30% faster”), include that in the description; it strengthens the case that your enhancement is substantive.

3. Include Necessary Details and Variations

An improvement patent is still a utility patent requiring full enablement. Provide drawings if applicable, and describe how to make and use the improved product or method. Consider variations and alternatives for your improvement; the broader you can describe it while remaining novel, the better the patent coverage you’ll get. One strategy is to describe and claim the improvement both in combination with the base device and as a standalone component.

4. Mind the Patent Timing and Rights

If the base product is under patent by someone else, you can file your improvement patent regardless. However, if the base patent is active, you don’t have the freedom to commercialize your version without dealing with that patent. Sometimes inventors coordinate with the original patent owner for licensing or cross-licensing arrangements, making your improvement patent valuable to larger companies that might pay to license your enhancement.

5. Leverage Provisional Applications When Useful

A provisional patent application can be a smart first step for improvements. If you’re still refining the improvement or gathering funds, a provisional lets you secure a filing date and “patent pending” status relatively cheaply. The filing fee is often around $150 for a small entity. You’ll need to file a corresponding non-provisional application within 12 months, claiming priority to the provisional application to maintain the original filing date.

This buys you time to build a prototype, conduct market research, seek investors or partnerships, or polish the invention details. However, ensure the provisional adequately describes your improvement; anything not described there will not receive the benefit of the early date.

6. Prepare for Examination and Possible Rejections

Improvement patents often face rigorous examination. Don’t be discouraged if the first Office Action comes back with rejections; that’s a common occurrence. Work with experienced patent counsel to craft responses: amend claims to distinguish over prior art, and argue why the combination the examiner made is not straightforward. Data and evidence showing surprising effects can rebut obviousness rejections. Persistence can pay off. Many initially rejected applications eventually get allowed after narrowing claims or providing convincing arguments.

7. Factor in Costs and Documentation

For a provisional application, you need a cover sheet, a specification describing the invention, any relevant drawings, and the filing fee (the micro-entity fee can be as low as $60). For a non-provisional application, you need a full, formal document with claims, an abstract, a detailed description, drawings, an inventor’s oath/declaration, and application data sheets. The filing, search, and examination fees for a non-provisional patent total a few hundred dollars for small entities, though working with experienced counsel on a fixed-fee basis provides transparency and predictability in your total investment.

Filing an improvement patent application involves clearly delineating what’s new and how it enhances the prior art. Strong research upfront, careful drafting, and sometimes a provisional first for flexibility all contribute to a smoother path. Focus on the improvement’s unique value – that’s your justification for a patent.

Provisional vs. Non-Provisional Patent Applications

Understanding these two routes is crucial when patenting an improvement, especially when considering the costs associated with obtaining a patent.

Provisional Patent Application

A provisional application is an optional first step that secures a filing date for your invention at a lower cost and with fewer formalities. It expires after 12 months and does not itself become a patent. During that period, you can label your invention “Patent Pending.” To continue, you must file a non-provisional application before the provisional lapses.

Advantages:

- Cost-effective and fast: Filing fees are small (often $150 or less for small entities), and you don’t need formal patent claims or complex formatting.

- Gives you time: Refine the improvement, test the market, seek funding before committing to the full application.

- Establishes official USPTO record: Critical in a first-to-file system where earlier filing dates generally win.

Non-Provisional Patent Application

This is the formal, examined patent application that can lead to an issued patent. It requires a complete disclosure, including claims, and is entered into the examination queue. A non-provisional application can be filed with or without a preceding provisional application. If you filed a provisional, the non-provisional claims priority to it, so the invention is treated as filed on the date of the provisional.

Advantages:

- Patent rights come from it—the only way to actually get a patent granted.

- The examination starts, although there may be a wait.

- Claims are defined, setting out the legal scope of protection.

Key Differences at a Glance

A provisional is simpler but temporary. A non-provisional must meet all formal requirements, will be published 18 months after filing, and is examined for patentability. Filing a provisional alone never results in a patent. You must follow with a non-provisional. The provisional’s benefit is primarily in timing and budgeting: lock in a date and delay bigger expenses.

Scenario Example: Suppose you invent an improved drone design. You’re still tweaking it, but want to secure a filing date. You can file a provisional application now with the details you have available. You spend the next 6-9 months refining the design and testing it. By month 10, you have a better prototype and more data to work with. You prepare a robust non-provisional application with detailed claims, filing it to claim the provisional’s date. Anything described in the provisional is protected as of that early date.

From a cost perspective, provisional applications have lower filing fees (e.g., $300 for large entities, $150 for small entities, and $60 for micro entities). Non-provisionals have higher combined fees (filing, search, examination) for a large entity, which can be around $ 1,000 or more, depending on the entity’s size.

Critical Warning: Don’t misuse the provisional. If your provisional is too skimpy and doesn’t adequately describe the invention, your priority date might be ineffective. While you can be less formal, ensure that the provisional teaches your improvement to a person skilled in the art, using drawings and examples as needed.

Use a provisional application when it aligns with your needs: securing a date quickly and buying time to perfect your improvement. If you’re fully ready and resourced, proceed directly to the non-provisional stage to initiate the process of obtaining a granted patent.

Working with a Patent Attorney

Statistics show that patent applications handled by professionals have significantly higher success rates. A study of 500 applications found that 76% of pro se (self-represented) applications were abandoned, compared to only 35% of those with attorney representation.

Figure 2: A study of 500 U.S. patent applications showed that 76% of pro se (self-filed) applications were abandoned, versus only 35% of applications with professional representation resulting in abandonment

Working with a patent attorney significantly enhances the chances of obtaining a patent and often results in stronger patent rights. Moreover, patents obtained with the assistance of attorneys typically have stronger claim coverage.

How a Patent Professional Adds Value

Expert Drafting: Patent attorneys craft applications that meet legal requirements and anticipate potential rejections. They write stronger claims that capture the broadest scope of your improvement without overstepping into prior art. For an improvement, this finesse is crucial. You need enough breadth to cover variations while avoiding existing technology.

Thorough Prior Art Searches: While you can do an initial search, experienced patent counsel can perform a deeper dive, finding obscure patents or foreign documents you might miss. More importantly, they interpret results and advise how to deal with them. They might identify that combining certain features differently creates the novel part worth focusing claims on.

Legal Strategy and Risk Management: Skilled counsel thinks ahead about infringement risks and can perform freedom-to-operate analysis to identify blocking patents. They can advise on alternative IP protection strategies and help manage timeline and costs, suggesting a provisional first if budget is an issue, or accelerating examination if you need an answer quickly.

Advocacy During Examination: When the USPTO examines your application, experienced counsel provides professional advocacy, drawing on knowledge of patent rules and precedents. They can counter obviousness rejections with legal arguments, point out where examiners misinterpreted aspects, and conduct interviews with examiners that often clarify issues and lead to allowance more quickly.

Higher Success Rates: The data speaks clearly. Represented applications are far more likely to result in issued patents, and the reason is apparent: patent prosecution is complex, and missing minor procedural points or not knowing how to argue effectively can significantly hinder an application’s progress.

Peace of Mind and Efficiency: Having experienced counsel means someone accountable for meeting deadlines and handling paperwork. Missing a filing deadline or response date can be fatal to a patent. Attorneys have docket systems to track these and handle formalities, such as electronic filing and formatting drawings to USPTO standards.

Fixed-Fee Advantage: While some patent attorneys charge hourly fees ($200-$400 per hour), working with a firm that offers transparent fixed-fee pricing eliminates billing surprises and lets you budget accurately. The value added often exceeds the cost, especially if your invention has commercial potential. If counsel helps you secure a robust patent you can enforce or license, the return on investment could be substantial.

While it’s legally possible to patent an improvement on your own, the expertise and guidance of experienced patent counsel can significantly enhance your success. They’re your advisor, draftsperson, negotiator, and advocate through the complex journey of turning your idea into a granted patent.

Avoiding Patent Infringement

When seeking to patent an improvement, you must be mindful of patent infringement issues – both not infringing others’ patents and protecting your own rights.

Your Improvement Patent Covers Only the Improvement

An improvement patent grants rights only to what you’ve added or changed, not to the entire underlying product. If you obtain a patent on a feature that improves a standard product, you do not automatically have the right to make or sell that product with your feature if someone else holds a patent on the base product.

The original patent is a “dominant” patent, and yours is an improvement or “subservient” patent. Collaboration or licensing is often the solution. Many improvements are brought to market through agreements with the original patent holder.

Diligently Search for Active Patents

Before commercializing your improved product, have experienced patent counsel conduct a freedom-to-operate (FTO) search that focuses on granted and in-force patents covering elements of the product. Identify any patents your improved product might inadvertently infringe. If you find such patents, you have options: design around those aspects, wait until the patent expires, or approach the patent owner for a license.

Expired Patents and Continuations

Often, when improving a product, you’ll find original patents have expired (especially for well-established products over 20 years old). That’s good – the base technology is public domain. However, be cautious about continuation patents or related patents still active. Companies sometimes file multiple patents around a product with later expiration dates.

In the pharmaceutical industry, follow-on drug patents for formulations or new uses are common. However, the USPTO has confirmed that these do not extend the original patent’s exclusivity. Once the original patent expires, generics can enter the market, provided they don’t infringe on active follow-on patents. This principle applies broadly: an improvement patent can’t resurrect expired patent coverage; it only applies to the improvement itself.

Designing Around Existing Patents

If your improvement relies on something patented, consider whether you can design around that patent. Patent claims are often specific; changing or omitting a claimed element can avoid infringement. Experienced patent counsel can analyze the claims of relevant patents and suggest modifications to prevent infringement.

Licensing and Cross-Licensing

If your improvement is valuable but you can’t avoid using a patented aspect of the base technology, licensing is straightforward. Negotiate with the patent owner (perhaps paying royalties) to practice their patent in combination with your improvement. Alternatively, if you obtain a patent for your improvement and it’s something others want, consider arranging a cross-license that allows them to use your base technology. You will enable them to use your improvement.

Act Quickly and Diligently

If you have a novel improvement, file your patent application before publicly disclosing or selling the product. In the U.S., you have a one-year grace period after your own disclosure to file, but foreign countries often have no grace period. Acting quickly also gets you in line at the USPTO, which can take, on average, approximately 19-20 months to send a first action and around 26 months in total to obtain a patent.

Monitor and Enforce

After obtaining your patent, keep an eye on the market. Ensure that others aren’t copying your improvements. Be prepared to send cease-and-desist letters or take legal action if necessary. Consult experienced counsel on developing an enforcement strategy. Often, a strongly worded letter referencing your patent can stop an infringer without a lawsuit.

By being proactive and thorough in your research, you can minimize infringement risk and protect your intellectual property innovation while safely bringing your improved invention to market.

Assessing Market Potential

Before investing significantly in patenting, assess whether your improvement has genuine market potential. Patents are means to commercial ends; they give a competitive edge, but only if there’s a market that values that edge.

Validate the Market Need

An improvement could be technically brilliant but have limited commercial value if it addresses a problem few people care about. Conduct market research: Who would be interested in purchasing this improved product? Why is it better for them? Is it a minor convenience or a game-changer?

Customer feedback is invaluable. Prototype the improvement and have users or focus groups test it to ensure it meets their needs. Their enthusiasm (or lack thereof) tells you a lot. A patent on an improvement consumers adore can be very valuable, whereas a patent on something technically neat but with no demand might sit on the shelf.

Size of the Market

Consider the size of the potential market. Patents have value roughly proportional to the market size they impact and the degree to which the improvement matters. If your improvement is for smartphone batteries, adding 10% more life, a vast market (millions of devices), likely significant interest, and a high licensing value. If it’s for specialized lab equipment used by only 100 labs worldwide, the market is small; however, the per-unit value might still justify patenting.

Competitive Landscape

Look at what competitors are doing or might do. If your improvement is truly novel, competitors might not have it yet. Getting a patent could block them or give you leverage. Assess if competitors would likely adopt your improvement if not for your patent. If it provides a real advantage (such as cost savings or a performance boost), competitors will likely want something similar, which is good news for the value of your patent.

Revenue Potential vs Patent Costs

Be realistic: obtaining and maintaining a patent will cost at least several thousand dollars. Does the potential profit from this invention justify that? If your improvement, when commercialized, could yield substantial profits or licensing fees, then the patent is a good investment. Try to outline a business case: estimate profit over X years and compare to patenting costs.

Enhancing Patent Value Through Market Success

Showing that your improved product has market traction can enhance the credibility and defensibility of your patent. In patent law, commercial success linked to the invention is a secondary consideration for non-obviousness. If your product hits the market and is a big hit specifically because of the patented feature, that can be used as evidence that the improvement was non-obvious.

Market Timing

Consider where the industry is headed. Is your improvement aligned with current trends or future needs? Patents last approximately 20 years, so you ideally want an improvement with staying power or applicability to next-generation products.

Investor and Partner Perspectives

If seeking investment or partnerships, having a patent (or pending application) on a valuable improvement can be a significant asset. Investors like to see IP protection because it means the company has a defensible niche. They’ll ask about market potential – investors want to know the patented improvement addresses a real need and can capture market share. For more on leveraging IP for fundraising, see our SaaS Agreement Checklist.

A patent doesn’t guarantee commercial success; it just gives you a chance to achieve it by excluding others. By validating that your improvement offers something the market values, you ensure your patent will have purpose. A well-targeted improvement patent, combined with good product and market strategy, can lead to significant rewards through product sales, licensing deals, or strengthening your IP portfolio.

Summary

Navigating the patent process for an improvement can be a challenging task. Still, improvements are the bread and butter of innovation, as most new patents are for enhancements to existing technology rather than entirely new inventions.

The Journey Recap

Ensure the Improvement is Patentable: Your idea must be novel, useful, and non-obvious. Conduct a reality check. Has someone already done this? The more you can articulate what makes it different and better from related prior art, the stronger your patent application will be.

Conduct a Thorough Prior Art Search: Don’t skip the homework. Investigate patents and publications in your field. This informs how you draft your application and prevents unpleasant surprises. Think of it as surveying the land before building a house.

Leverage Professional Help: Working with experienced patent counsel is highly advised. Data show that professional guidance matters in increasing the odds not only of getting a patent application approved but also of getting one approved with broad coverage. Attorneys will help you avoid pitfalls, such as inadvertently infringing on others’ patents, and save time and money by responding effectively to USPTO correspondences and Office Actions.

Choose the Right Filing Strategy: Decide between a provisional application (quick, temporary) and a full non-provisional application based on your readiness and needs. Many inventors file provisional patents to secure a filing date while refining their invention. Understand the timeline: it can take several years to obtain a patent, so plan accordingly.

Draft a Strong Application: Clearly highlight how your improvement works and explain why it may not be immediately apparent. Use examples, data, and comparisons if helpful. Don’t be discouraged by initial rejections; they’re common. With persistence and solid reasoning, you can often obtain the patent.

Mind the Business Aspects: A patent is one piece of the puzzle. Make sure you’ve considered whether this improvement has a market. Patents can be expensive, so have confidence that the protected invention will generate value through product sales, licensing, or strategic advantage.

Plan for Infringement Avoidance and Enforcement: As you navigate patenting, think about existing patents (to avoid infringing) and how you’ll enforce your rights once you have them. Be proactive: if you are aware of a relevant patent, address it by designing around or licensing it. Once you have your patent, monitor the market.

Consider Alternatives if Needed: If patenting doesn’t make sense due to cost, difficulty, or a short product lifespan, remember that there are other ways to protect your innovation, such as trade secrets or rapid market entry.

Final Thoughts

By following this guide, you’ll be well-equipped to navigate the complexities of patenting an improvement. We covered identifying what qualifies as an improvement, satisfying the non-obviousness standard with evidence and sound arguments, conducting prior art searches to lay a strong foundation, the mechanics of filing applications, and leveraging professionals. We also touched on infringement avoidance, market considerations, and alternative IP strategies.

The key takeaways are to conduct thorough research, document your innovation carefully, seek sound advice, and think strategically about both legal and market factors. Patenting an improvement is both a legal project and a business project.

Many successful products and companies have been built on improvement patents, from minor tweaks that became must-have features to new uses of old products that unlocked entire new markets. Your idea, however small it may seem, could be the next success story. With a patent in hand, you’ll have the confidence and investor appeal to push it forward, knowing you have a period of exclusivity to capitalize on it.

Don’t underestimate the value of your idea. If it truly adds something novel and useful beyond the status quo, patent protection can be a powerful asset. By carefully navigating the process, you can secure that asset and use it to advance your entrepreneurial or inventive goals.

Your Next Steps to Improvement Patent Success

You’ve learned that most patents protect incremental improvements, not groundbreaking inventions – and that with the right strategy, your enhancement could be the next Amazon One-Click or Gillette Mach3. Proper guidance transforms uncertain ideas into defensible competitive advantages that attract investors, deter competitors, and build real market value.

The bottom line: Weak improvement patents invite design-arounds and competitive attacks. Strong improvement patents, backed by thorough prior art analysis and strategic claim drafting, create lasting barriers that force competitors to innovate elsewhere.

Here’s what’s at stake: Without professional guidance, you risk filing applications that get rejected for obviousness, wasting time and money. In contrast, your competitors file first in our first-to-file system. Every day you delay allows rivals to patent similar improvements, blocking your path to market. Poor prior art searches leave you vulnerable to infringement claims. Generic claim language fails to capture the full value of your innovation.

Take these immediate steps to protect your improvement:

- Schedule a Free IP Strategy Call with our patent team to evaluate your improvement’s patentability, identify prior art risks, and develop a strategic protection plan tailored to your business goals.

- Commission a comprehensive prior art search to validate novelty and inform your filing strategy.

- Determine whether a provisional filing makes sense to secure your priority date while you refine the invention.

- Assess freedom-to-operate risks to ensure you can commercialize your product without infringing on existing patents.

- Develop a budget-conscious filing roadmap that maximizes protection while managing costs.

Your improvement represents genuine market differentiation and investor value, but only if you protect it correctly. The right patent strategy, executed with precision and backed by thorough research, transforms incremental innovations into formidable competitive moats. The investment you make today in proper patent protection delivers returns through licensing revenue, acquisition premiums, and market exclusivity for years to come.

The RLG Advantage for Provisional Patents:

- FREE strategy call with the RLG team.

- Experienced US patent attorneys lead the application from start to finish.

- One transparent flat fee covering the entire provisional patent application process

- Full refund if USPTO denies provisional patent application*.

- Full refund or additional searches if the application has patentability issues (your choice)*.

To Your Success,

Andrew Rapacke, Managing Partner

Registered Patent Attorney

Rapacke Law Group

Connect with us:

LinkedIn: Andrew Rapacke

Twitter/X: @rapackelaw

Instagram: @rapackelaw