In August 2025, the USPTO terminated 52,000 trademark applications and registrations in a single enforcement action. The reason? Fraudulent specimens and false claims of use in commerce. The sanctioned entity had systematically submitted fraudulent evidence: digitally created mockups, fabricated sales records, and specimens showing marks that were never used on products sold to actual customers.

This wasn’t an isolated incident. USPTO random audits from 2017 to 2023 found that approximately 50% of examined registrations couldn’t demonstrate use for all claimed goods and services, requiring owners to delete items from their registrations. More striking: 13% of audited registrations were cancelled entirely for complete nonuse.

These numbers expose a fundamental misunderstanding that costs businesses their trademark rights: many applicants treat “use in commerce” as a formality to check off rather than a substantive legal requirement they must genuinely satisfy. Meeting legal requirements is essential for trademark registration and ongoing protection. The difference between real commercial use and token use isn’t just technical; it determines whether your trademark rights survive challenges, enforcement actions, and maintenance requirements years after registration.

Understanding what constitutes legitimate use in commerce isn’t optional. It’s the foundation of every enforceable U.S. trademark right and a critical aspect of intellectual property protection. Establishing rights through proper use is necessary for the trademark owner to secure and maintain legal protection.

To establish trademark rights in the US, a trademark owner generally must be the first to use a mark in commerce on particular goods or services. This principle ensures that rights are granted to those who demonstrate genuine, bona fide use in the marketplace.

Answering the Core Question: What Is “Trademark Use in Commerce”?

Trademark use in commerce is the foundation of all U.S. trademark rights. Under Section 45 of the Lanham Act (15 U.S.C. § 1127), “use in commerce” means the bona fide use of a mark in the ordinary course of trade, not token use made merely to reserve rights in a mark. Without actual use in commerce, you cannot federally register a trademark based on actual use, and you have no common law trademark rights to enforce.

Here’s what that means in practical terms:

- Congress must lawfully regulate commerce, meaning interstate commerce (crossing state lines), territorial commerce (to Puerto Rico, Guam, etc.), or trade between the U.S. and a foreign country.

- The term “trademark in commerce” refers to the legal requirement that a trademark be used in commerce, such as in sales or transactions, to establish rights and obtain federal registration.

- For goods, the mark must appear on products, labels, packaging, or point-of-sale displays, and those goods must be sold or transported in qualifying commerce.

- For services, the mark must be used or displayed in advertising where the services are actually rendered to customers in commerce.

- Advertising alone is not enough for goods; you need actual sales or shipments. Advertising alone is not sufficient to constitute use in commerce; there must be an actual sale or service rendered to the public.

- Purely local, intrastate activity typically won’t support federal registration unless it affects interstate commerce.

A trademark cannot be federally registered with the federal government until it is being used in commerce. As of 2024, the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), the federal patent and trademark office, maintained over 3.2 million active trademark registrations and received approximately 737,000 new applications in 2023 alone. Each registration required proof of genuine commercial use, and applicants must disclose the date of first use in commerce to the United States Patent and Trademark Office as part of the registration process.

Legal Definition of “Use in Commerce” and Bona Fide Use

Section 45 of the Lanham Act states that use in commerce means “the bona fide use of a mark in the ordinary course of trade, and not made merely to reserve a right in a mark.” The phrase “bona fide” is doing heavy lifting here. It means genuine, real commercial activity: the kind of transactions your business would make regardless of whether you were filing a trademark application. Only such use. Actual selling or transporting of goods, or rendering of services in commerce, qualifies as use in commerce under the statute. Established use allows for infringement claims against others whose similar marks cause consumer confusion.

Key points about what the statute requires:

No sham transactions. Bona fide use excludes token transactions, such as selling one item to a friend for $1 solely to claim trademark rights. The USPTO and courts will see through such tactics. For example, selling one item to a relative who immediately returns it creates a record of use without any real commercial activity, precisely what the law prohibits.

“Ordinary course of trade” varies by industry. What counts as everyday use depends on your business model. A small online t-shirt shop is expected to have frequent sales, whereas a company selling jet engines makes only a few high-value sales per year. The law recognizes these differences; the key is that use is ordinary and expected for that line of business, not an anomaly manufactured to reserve rights.

Use must be lawful. Using a mark in an illegal business doesn’t create enforceable trademark rights. Selling contraband or operating in violation of federal law won’t count as “lawful use in commerce.” This issue frequently arises with businesses in federally regulated markets. For example, cannabis dispensaries cannot obtain federal trademarks for marijuana products because the underlying commerce violates federal law, even in states where such sales are legal.

No “warehousing” of marks. The whole purpose of the use requirement is to prevent people from simply reserving or “warehousing” trademarks without actually using them. Trademark law wants to keep the market free for businesses that are genuinely using marks. If marks could be claimed without use, individuals or companies could hoard names and unfairly block others.

Courts take a hard line on token use, even for major corporations. In 2024, a federal court found that Reebok committed fraud on the USPTO by claiming use of its “RBK” trademark when it wasn’t genuinely using it. Reebok had stopped selling RBK-branded goods by 2010, but in 2012 (to renew the registration), they placed small “RBK” stickers on the inside of shoe boxes of other products purely to create the illusion of use. The court noted this was not a bona fide commercial use. Customers weren’t seeing RBK or buying RBK-branded shoes; the shoes were Iversen-branded, with RBK only hidden inside the box, where consumers would never see it.

The judge ruled that this was essentially a scheme to “merely reserve rights” in the mark, rather than actual trademark use. The court deemed the renewal to be jeopardizing Reebok’s RBK trademark registration and even evoking the attorney-client privilege under the crime-fraud exception. This case illustrates that “use” has to be genuine. Simply affixing a mark that consumers won’t even see, solely to keep a trademark registration alive, is not acceptable.

Trademark Use in Commerce for Goods vs. Services

The USPTO and courts apply different evidentiary standards depending on whether you’re registering a trademark for goods or a service mark for services. Understanding this distinction is critical for your trademark application. For service marks, the ‘person rendering’ the services must be actively providing those services in commerce for the use to qualify as trademark use in commerce.

For Goods (Trademarks)

When your mark covers physical products, the Lanham Act requires that the mark be “placed in any manner on the goods or their containers or the displays associated therewith or on the tags or labels affixed thereto.” If placement is impracticable due to the nature of the goods (e.g., large or expensive items such as industrial machinery), the mark may appear on documents associated with the goods or their sale. This situation is referred to as ‘placement impracticable’ under USPTO regulations, allowing alternative placement to establish trademark use in commerce.

The goods must then be sold or transported in commerce. This typically means:

- Shipping products across state lines at the trademark owner’s direction or knowledge.

- Selling goods to customers in more than one state.

- Exporting products to a foreign country.

Example: A coffee roaster in California ships branded 12-oz bags to customers in Nevada in January 2024. The mark appears on the packaging, and the sale crosses state lines. This is a classic use in commerce for goods.

The USPTO’s specimen guidelines explicitly state that for goods, advertising materials alone are unacceptable unless they constitute point-of-sale displays. A point-of-sale display must display the trademark near the product and include a purchase or order option, such as a purchase button or pricing information. An online retailer’s product page with an “Add to Cart” button qualifies. A promotional flyer showing the product name and picture without pricing or ordering information does not.

For Services (Service Marks)

Service marks work differently. The mark must be “used or displayed in the sale or advertising of services,” and those services must actually be rendered in commerce.

Acceptable evidence includes:

- A branded website homepage that describes the services and shows how to contact or engage with the provider.

- Online advertisements or brochures displaying the mark in connection with the service offering.

- Screenshots of app interfaces where services are delivered.

- Invoices or contracts with the branding are issued to clients for services rendered.

Example: A tax preparation firm launches a branded website in February 2024 and serves clients located in Texas, Oklahoma, and Louisiana. Website screenshots showing the mark, service descriptions, and contact information would serve as specimens for a trademark application.

The key difference: for goods, ordinary advertising materials are typically rejected as specimens. For services, marketing materials that clearly offer the services are acceptable, provided the person providing those services is actually doing so in commerce. The USPTO explicitly lists brochures, leaflets, print ads, and online ads as acceptable specimens for services, assuming the services are actually available at that time.

What Kind and Amount of Use Counts as Bona Fide Use?

One of the most common questions trademark applicants ask is: “How much use is enough?” The answer is frustratingly fact-specific, but there are clear guideposts from USPTO practice and case law.

The core principle is that your use must reflect genuine commercial activity in the ordinary course of your business, not isolated, trivial, or contrived transactions designed only to support a filing. What qualifies as sufficient trademark use in one industry may differ significantly across sectors, as industry standards can vary.

What Usually Qualifies as Sufficient Use

- Regular sales or ongoing shipments of branded products to customers in multiple states. Even if numbers aren’t huge, consistent sales or ongoing shipments over time show a continuing effort to penetrate the market. A small craft brewery that ships a few cases each month to liquor stores in two neighboring states is likely engaged in bona fide use.

- Regular provision of services under the mark to paying clients. A freelance graphic designer with a steady stream of client projects under their brand, including clients across state lines, is making bona fide use of their service mark.

- Documented marketing and distribution efforts paired with actual availability of goods or services. If you’re investing in fulfilling customer orders as they come, that supports genuine use.

- Even modest sales volume, if consistent with how your industry typically operates. Bona fide requires having a large generating company with millions in revenue. You need to be doing what a real business in your position would typically do to commercialize the market.

Industry-Specific Considerations

What counts as “ordinary” varies dramatically across industries:

- A custom software B2B business might only make a few high-dollar sales per year. That can still be bona fide use if those sales are legitimate and align with how such companies operate.

- Pharmaceutical companies may ship products to clinical investigators or trial sites during drug development. For example, a company awaiting FDA approval may ship a new drug to clinical investigators or test markets. Even though these aren’t traditional sales, courts have found that such shipments, even before FDA approval, can constitute use in commerce for pharmaceutical marks when they cross state lines, because they are part of the normal course of trade leading up to commercial distribution.

- A boutique jewelry designer might sell only a handful of pieces at art fairs and on Etsy, but if those are genuine sales to the public and the business is ongoing, that’s the norm for that type of business.

What Doesn’t Qualify

Courts and the trademark office look skeptically at:

- Token or artificial sales designed only to “check the box.” One-off shipments to friends, relatives, or shell entities, timed just before filing, will be viewed skeptically. Shipping one pallet of goods to a friend in another state with no intent to sell beyond that is a red flag.

- “Sales” where money isn’t really at risk or changing hands meaningfully. Deeply discounted or free transfers to insiders, or transactions immediately reversed (like the $1 sale-and-return scenario), indicate there’s no real market for the product.

- No follow-up activity. If you made a couple of sales many months ago and then nothing else, it could appear that those sales were manufactured just to support a trademark filing. For example, selling one item in January, filing an application in February claiming that use, and then not selling anything else the rest of the year suggests the January sale was a token use.

- Creating invoices without ever delivering products. If evidence later shows no actual product was exchanged or services rendered, the claimed use is illegitimate.

The Reebok RBK case illustrates that even significant sales volume doesn’t help if those sales don’t use the mark in a brand-identifying way. The court noted that, although Reebok had substantial sales, those sales didn’t reflect the RBK mark as consumers perceived it; customers weren’t buying RBK-branded shoes. What mattered was that consumers didn’t perceive those sales as sales of RBK products.

What Does “Commerce” Mean for Trademark Purposes?

Commerce under the Lanham Act is broader than just “doing business.” It’s tied directly to Congress’s constitutional power to regulate interstate and foreign trade.

Qualifying commerce includes:

- Interstate commerce between two or more U.S. states.

- Territorial commerce (e.g., sales to Puerto Rico, Guam, or the U.S. Virgin Islands).

- Commerce between the U.S. and foreign countries (both exports and imports).

What About Purely Local Businesses?

Historically, purely intrastate commerce (operating only within one state) was not eligible for federal registration. However, the modern interpretation of the commerce requirement is broader. If your local business has any effect on interstate commerce, it may qualify.

Consider two scenarios:

Scenario A: A bakery in Austin, Texas, serves only walk-in customers from the local neighborhood. No online sales, no shipping. This is purely intrastate and would not support a federal trademark application based on use.

Scenario B: The same bakery starts shipping branded cookie boxes to customers in Oklahoma in 2024 and advertises nationwide through Instagram. Now there’s interstate commerce, and the business can seek federal registration.

There’s a landmark case on this issue: Christian Faith Fellowship Church v. Adidas (Fed. Cir. 2016). A church in Illinois sold two hats bearing its mark to a customer from Wisconsin. The sale itself took place in Illinois, but the purchaser was an out-of-state resident. The USPTO initially said that it wasn’t interstate commerce since the goods didn’t literally cross state lines.

However, the appellate court held that this did count as use in commerce. The court reasoned that if you look at the transaction “in the aggregate,” local sales to out-of-state customers could, over time, have a substantial effect on interstate commerce, and that’s enough under the Commerce Clause. The church didn’t have to prove the hats went out of state or that those two sales alone affected commerce; it was enough that selling to an out-of-state resident is the kind of activity that, in aggregate, Congress can regulate.

This case effectively broadened the hold interpretation to allow a single intrastate sale to an out-of-state customer to satisfy the “use in commerce” requirement.

Bottom line: If there’s any interstate aspect (even a small one), you likely meet the commerce requirement. It could be one interstate sale, an out-of-state client, interstate advertising and shipping, or even the movement of customers across state lines.

One important note: Having a website that is merely accessible nationwide is not, by itself, “use in commerce.” You need an actual transaction or provision of a service across state lines. If you put up a website for your local business and someone in another state could access it, then, whether or not they actually use it, it’s not yet in commerce. The first actual out-of-state sale or client is what establishes qualifying use.

Date of First Use: “Anywhere” vs. “In Commerce”

U.S. trademark applications require a trademark applicant to provide two specific dates: the date the mark was first used anywhere and the date the mark was first used in commerce. Confusing them is one of the most common mistakes applicants make. Both must be provided in month/day/year format.

Date of First Use Anywhere

This is the earliest date on which the mark was used on or in connection with the goods or services, anywhere in the world, even if used solely locally or in a foreign country.

Example: You started using your brand name on a website accessible only in Canada in March 2022. That’s your first use anywhere date.

Date of First Use in Commerce

This is the first date on which goods were sold or transported, or services were rendered, in commerce regulable by Congress: interstate, territorial, or U.S./foreign commerce.

Example: You made your first interstate sale in the U.S. on June 15, 2023, shipping products from New York to New Jersey. That’s your first use in commerce date.

Critical Rules About These Two Dates

- The first use in commerce date cannot be earlier than the first use anywhere date. Logically, you can’t have used the mark in interstate commerce before you’ve used it at all. The USPTO will reject a filing where the in-commerce date precedes the anywhere date.

- Both dates must reflect the same type of use shown in your specimens. The dates you claim should match what your specimen shows. If you claim first use in commerce on July 1, 2023, your specimen should show use around that time. If your first use was on one type of goods but your application lists a broader range, you need to have used it on all listed goods by that date.

- Use must precede application (for use-based filings). In a Section 1(a) use-based application, you cannot claim a first use date that is after the filing date. If you accidentally file too early and your claimed first use is actually after filing, you have a problem: you may need to amend the filing basis to intent-to-use or face an Office Action.

- Changing these dates after filing can be tricky. The dates of first use are part of your sworn statement in the application. If you later realize you got them wrong, you can attempt to amend them, but you must verify the correction. You typically can’t amend a date after filing in a use-based application, and you can’t amend to an earlier date than initially claimed because that might raise fraud concerns.

Getting these dates wrong can trigger an office action from the trademark office or, worse, provide grounds for a competitor to challenge your registration later. Always double-check your research to get the dates right the first time.

Evidence of Use in Commerce: Specimens for Goods

When you file a trademark application based on actual use, you must submit a specimen: physical evidence that your mark is being used in commerce on the goods. Getting this right is essential to avoid refusals.

What the USPTO Accepts for Goods

According to USPTO specimen guidelines:

- Photographs of the mark on product labels, tags, or packaging. This could be a photograph of your product’s label with the brand name, or of the box the product comes in, if it has the trademark printed on it. A clothing brand could submit a photo of the clothing tag or hangtag showing the mark.

- Screenshots of online product listings (e.g., a 2025 Amazon listing) clearly showing the mark, the product, and an order button (e.g., “Add to Cart” or “Buy Now”). The USPTO is increasingly accepting website screenshots as specimens of goods when the page includes the trademark near the product and provides a purchase link.

- Point-of-sale displays enable customers to purchase products directly. If you have a printed catalog, a catalog page with an order form or phone number for ordering can work.

What Typically Gets Refused

- Advertising brochures or flyers without ordering information. If you submit a glossy brochure or web advertisement that simply promotes the product, it will likely be treated as advertising rather than as proof of actual sales or shipments.

- Company profile pages that don’t show specific products. Press releases announcing a product launch, or newspaper articles reviewing your product, even if they show the product name, are not proof of trademark use by you.

- Mockups or “coming soon” images for products not yet available. The USPTO has stated that webpages showing goods “not yet available” (like pre-sale without delivery) are not acceptable specimens. You need to show the product as available for sale or in stock for shipment.

- Promotional materials showing the mark but no actual goods. If you submit what appears to be a digitally created product image (not a photo of a real product) or a “printer’s proof” of a label, the USPTO often rejects it, stating it’s not evidence of actual use in commerce.

A Common Problem and How to Fix It

Suppose you submit a promotional flyer that shows your brand name but includes no pricing, product details, or ordering information. The examining attorney issues an office action refusing your specimen.

Your response options:

- Submit a substitute specimen that predates your filing date and shows the mark on actual products or a functional point-of-sale display. For example, if your first attempt was a brochure (refused) and you have photos of the product with labels that were in use before your filing date, you can submit them with a declaration.

- If no such specimen exists, you may need to amend to an intent-to-use application (if eligible within specific time frames and circumstances). However, it’s generally better to file as ITU from the start if you haven’t genuinely used the mark at the time of filing.

The specimen must reflect actual use in commerce as of the date claimed, not aspirational marketing for products you hope to launch.

Evidence of Use in Commerce: Specimens for Services

Service marks require different proof. Because services are intangible, the USPTO accepts advertising and marketing materials, provided they show the mark used in connection with services that are actually being rendered.

Acceptable Specimens for Services

- Branded website homepages or landing pages describing the services and showing how to contact or engage. For example, if you run a consulting firm, a screenshot of your homepage showing the firm’s logo and a text such as “Offering management consulting services to clients nationwide” is ideal.

- Online advertisements or brochures displaying the mark and the nature of the services. A landscaping company could submit a scanned booklet that has the company name/logo and lists landscaping services offered.

- Screenshots of app interfaces that provide user services.

- Business cards or letterhead are used to promote services, but they are less effective unless they explicitly state the service. A law firm’s letterhead reading “Smith & Doe LLP – Immigration Law Attorneys” would associate the name with legal services.

- Invoices or receipts showing the mark and describing services rendered. An invoice on the consulting company’s letterhead/logo demonstrates that you provided the service to a paying client under that mark.

Key Requirements

- The specimen must reference the specific services listed in your application (e.g., “legal services in the field of immigration law,” not just a firm name with no context). It’s not enough to just show the mark in a vacuum; the USPTO wants direct association with the services.

- The services must actually be rendered. A “coming soon” page doesn’t qualify. If you launch a website advertising a future service that isn’t yet being provided, that’s not actual use.

- Simply reserving a domain name with your mark isn’t useful. For instance, if you registered a domain and the page just displays the name and “Under Construction,” that’s not for commercial use.

A Concrete Example

A consulting firm adopted a new brand name and launched its website in January 2024. The site described their management consulting services and included contact forms for potential clients. By March 2024, they had served clients in California, Texas, and Florida.

Strong specimens would include:

- Website screenshots from January 2024 showing the mark and service descriptions.

- Client invoices showing services rendered under the mark.

- LinkedIn advertisements displaying the mark in connection with consulting offerings.

Pre-Sales Activity, Beta Testing, and Crowdfunding

Modern businesses often engage in marketing, beta testing, and crowdfunding long before their products hit the market. But not all pre-launch activity qualifies as use in commerce.

Marketing Alone Isn’t Enough

Press releases, trade show booths, and Kickstarter campaign pages that do not include actual shipments are considered pre-sales activity. They don’t meet the “sold or transported” standard for goods. You might create buzz with social media or a splashy unveiling at a trade show, but if you’re not yet actually selling the product or delivering the service, it’s not use in commerce. Showcasing a prototype at a trade show and taking names of interested customers is valuable for business. Still, until you actually fill an order, you haven’t “used” the mark in commerce.

Software and Digital Products

For apps and software, use in commerce typically begins when the product is publicly released and downloaded by customers, not during internal testing—a stage when companies should also be mindful of potential overseas infringement issues.

- Closed beta (August–October 2023): A mobile app tested only by internal team members and a handful of invited testers under NDA likely doesn’t qualify as use in commerce. If testers are not being paid and are essentially helping you develop the product, that’s not the ordinary course of trade.

- Public launch (November 2023): The app goes live on the App Store, and users in multiple states download it. This is when commercial use begins.

External beta tests with real users might qualify if those users are in the ordinary course of trade and not just employees or close associates. If your “beta” is more like a soft launch, with real customers using the service regularly, you may be able to treat it as first use.

Crowdfunding Campaigns

Crowdfunding pages on Kickstarter or Indiegogo are typically viewed as offers to sell, not actual sales. During the campaign, no goods have been delivered, so the campaign page is essentially advertising/pre-sale, not yet in commerce.

However, if you are a SaaS startup, it’s crucial to understand why securing trademarks early is essential for your business:

- Once you ship “reward” products to backers in multiple states under the mark, that constitutes use in commerce.

- A hardware device that shipped to backers in 15 states following a 2022 crowdfunding campaign has been in commercial use since shipment.

For example, suppose you develop a new gadget called “GizmoPro,” run a Kickstarter in 2022, and by mid-2023, you ship the product to 500 backers in 40 states. You have clearly used “GizmoPro” in commerce as of that shipping date. The Kickstarter page being live earlier doesn’t count; it was an offer to sell, but not an actual sale or transport of goods. For guidance from legal professionals experienced in intellectual property and commerce matters, consult the team at The Rapacke Law Group.

The bottom line: your mark isn’t “in use” until authentic goods reach real customers, or real services are rendered.

Meaningful Sales vs. Token or Sham Transactions

There’s a crucial difference between bona fide commercial activity and token use designed only to support a trademark filing. Sometimes, a trademark owner asks an employee or friend to make a purchase or sale to create the appearance of legitimate commercial use; such actions are considered sham transactions and do not qualify as actual use in commerce. Courts and the USPTO take this distinction seriously, and the consequences of getting it wrong can be severe.

What Token Use Looks Like

- A single $10 sale of branded goods to a friend in 2021 immediately returned.

- Deeply discounted “sales” to insiders with no genuine market presence.

- Creating invoices but never delivering products.

- “Friends and family only” sales made days before filing with no follow-up.

What the USPTO and Courts Consider

When evaluating whether use is genuine, decision-makers look at:

| Factor | What They Want to See |

| Continuity | Andrew Rapacke specializes in ongoing or repeat transactions, not one-off sales |

| Marketing efforts | Genuine attempts to reach customers |

| Inventory and distribution | Real products available for purchase |

| Customer base | Actual third-party buyers, not just insiders, may be interested in innovations protected by a patent. |

| Industry norms | Activity consistent with how similar businesses operate |

In August 2025, the USPTO announced it had sanctioned a foreign entity and terminated more than 52,000 trademark applications and registrations found to involve fraudulent specimens and false claims of use. This massive crackdown shows how seriously the USPTO takes sham usage. Creating fake invoices or phony photographs, or submitting doctored images as specimens, can result in not just refusal but sanctions.

Industry-Specific Exceptions

Some industries naturally have infrequent sales. A company building satellites might have only 2-3 sales per year, but each sale is a multimillion-dollar contract; that’s normal for the industry, and those sales are bona fide, even if small in number. The context matters. The key is that those sales were real, arm’s-length transactions in the marketplace, not sham arrangements.

Bad-faith or token use can lead to refusals during examination, or cancellation proceedings years later if competitors challenge your mark. The USPTO can refuse an application if it suspects the specimen is a sham. Even after registration, a competitor could challenge your trademark in a cancellation proceeding, arguing the mark was not in use as of the application’s filing date or that the use was a sham.

Intent-to-Use (ITU) Applications When You Don’t Yet Have Use in Commerce

What if you want to protect a mark before your product launches? Section 1(b) of the Trademark Act allows you to file an ITU application based on a bona fide intention to use a mark in commerce.

How ITU Applications Work

- File your ITU application with a bona fide intent to use the mark on the identified goods or services. You do not need to provide specimens at this stage.

- Receive a Notice of Allowance from the USPTO after examination. If the application clears examination and any opposition period, the USPTO issues a Notice of Allowance, essentially an invitation: “We’re ready to register your mark once you show us you’ve used it.”

- Submit a Statement of Use with specimens showing actual use within 6 months of the allowance date.

- Request extensions as needed, up to five additional 6-month periods (36 months total from the allowance). Each extension requires a fee and a signed statement confirming your intent to use the mark.

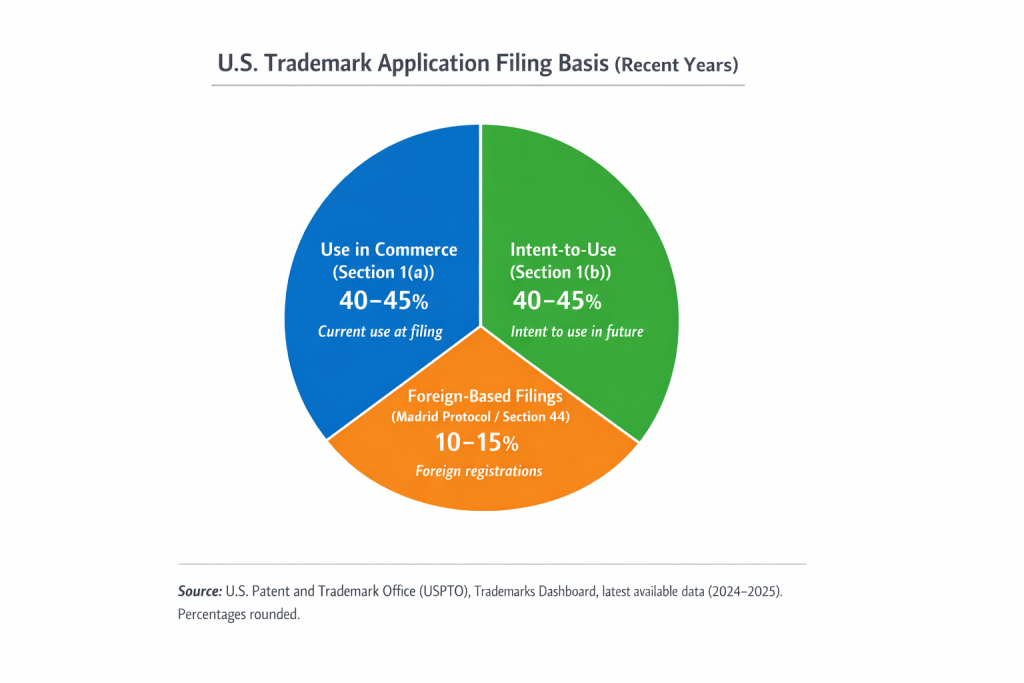

Figure 1: Trademark Use in Commerce vs. Intent-to-Use Filings: Nearly half of all U.S. trademark applications are filed without claiming current trademark use in commerce, relying instead on intent-to-use filings. This data underscores a critical strategic point: when use is uncertain or still developing, filing as intent-to-use is not an exception—it is a mainstream, risk-reducing approach that avoids false use claims and future cancellation exposure.

Strategic Advantages of ITU

An ITU application reserves your priority date as of your trademark application filing date. If a competitor starts using a similar mark after you file, your earlier filing date gives you priority, as long as you eventually prove use. When you file an ITU, it’s as if you planted a flag on that filing date. You get nationwide priority dating back to your filing date, even though you weren’t using the mark at that time.

This is particularly valuable for:

- Startups are still in product development.

- Companies rebranding before a public launch.

- Businesses with a bona fide intent that haven’t finalized manufacturing.

According to recent USPTO filing statistics, approximately 45% of new trademark applications are filed on an intent-to-use basis, roughly equal to the proportion filed based on actual use. This demonstrates that ITU is a common, widely used strategy for businesses seeking protection before launch.

When to Choose ITU Over Use-Based Filing

If your use at the time of filing is borderline or minimal, an ITU application is often the safer choice. Claiming use when you don’t have sufficient use can lead to fraud allegations and cancellation.

Example: A startup names its new energy drink in early 2025 and files an ITU application in March, months before production is complete. After launching across multiple states in September, they submitted a Statement of Use with photos of the branded bottles and shipping invoices. Critically, their protection dates back to March 2025.

The Risk of Missing Deadlines

If you fail to file a Statement of Use or an extension request within the allowed timeframes, your application will be abandoned. The USPTO is strict about these deadlines, and missing them means losing your priority date entirely. Many ITU applicants set reminders every 6 months to track their extension deadlines.

Filing an ITU is a promise. You are declaring under oath that you have a bona fide (good faith) intention to use the mark in commerce. If that wasn’t true (if you were just hoarding the name with no real intent to launch), the application or resulting registration can be challenged as void for lack of bona fide intent. In a 2024 case involving a viral TikTok phrase, an individual filed a trademark for a catchphrase they didn’t originate and had no business using. Such opportunistic filings often fail when challenged for lack of real intent.

Maintaining Trademark Rights: Continued Use, Nonuse, and Abandonment

Establishing commercial use leads to federal registration. However, maintaining your trademark rights requires continued use.

Maintenance Filing Requirements

After registration, you must file periodic declarations proving ongoing use:

| Filing | Deadline | What’s Required |

| Section 8 Declaration | Between years 5-6 after registration | Specimen showing current use; verified statement |

| Section 8 + Section 9 Renewal | Every 10 years after registration | Specimen showing current use; renewal fee |

Miss these deadlines, and your registration gets cancelled. There are no automatic reminders from the trademark office. The USPTO sends reminders to addresses on file, but ultimately it’s the owner’s responsibility.

The Abandonment Presumption

Under trademark law (15 U.S.C. § 1127), three consecutive years of nonuse create a presumption of abandonment. This means:

- If you stop using your mark for three years, it’s presumed abandoned.

- Third parties may petition to cancel your registration for nonuse.

- You can rebut this presumption only by demonstrating an intent to resume use (e.g., by documenting relaunch plans during a temporary shutdown).

In a 2024 Fourth Circuit case (Simply Wireless v. T-Mobile), Simply Wireless held a common-law trademark “SIMPLY PREPAID” that it hadn’t used from 2009 to 2011. T-Mobile later adopted “Simply Prepaid,” and a lawsuit followed. T-Mobile argued that Simply Wireless abandoned the mark during that period of nonuse. Simply Wireless said it was negotiating a license with a third party and kept the domain name active during those years, indicating it didn’t intend to abandon it.

The trial court sided with T-Mobile (finding abandonment). Still, on appeal, the Fourth Circuit held that evidence of intent to resume (licensing discussions, domain maintenance) was sufficient to raise a factual issue for trial at a minimum. The court also clarified that the same standard for abandonment applies to common law marks just as to federally registered marks.

Recent case law emphasizes that even a good reason for nonuse doesn’t save a trademark from abandonment unless accompanied by intent to resume use. In the To-Ricos v. Productos Avícolas Del Sur case (1st Cir. 2024), a company tried to argue it didn’t use its mark for several years due to protracted litigation with a bank (a “good reason”). But the court said that doesn’t toll the three-year rule. They still presumed abandonment because no actual use occurred, and the company couldn’t show firm, meaningful steps to resume use soon.

Audit Data Shows the Risk

From 2017 to 2023, USPTO random audits found that approximately 50% of audited registrations couldn’t prove use on all goods/services and had to delete some items. More strikingly, about 13% of audited registrations were fully cancelled due to complete nonuse. This underscores the importance of continuous use and proper documentation.

The lesson: if you’re not using your mark, you’re at risk of losing legal protection.

Practical Tips for Proving and Documenting Use in Commerce

Smart businesses don’t wait for a dispute to start documenting their trademark use. Here’s a practical checklist for building a solid record:

Records to Keep

- Invoices and shipping records showing sales to customers in other states or foreign countries, with dates. Save invoices, order confirmations, packing slips, shipping receipts; anything that shows you sold a product under the trademark to someone in another state on a specific date.

- Website screenshots (dated) showing the mark, product or service descriptions, and ordering or contact options. Take dated photographs of your product in use. When you produce your first batch of branded products, photograph them.

- Marketing campaign records are tied to periods when goods or services were actually available. While ads alone aren’t proof of use, they provide helpful context. Save copies of any advertisements, brochures, or press releases along with dates and where they ran.

- Photographs of products with labels, packaging, and tags displaying the mark. If you have a factory or fulfillment process, take pictures of the product being packaged for shipping, showing the labels.

Best Practices

- Archive versions of your website periodically (keep 2023 and 2024 copies, for example) in case content changes, but you need to prove what appeared on a specific date. Use web archiving tools, such as the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine, to create independent records with timestamps.

- Align internal launch dates with your claimed first use in commerce dates; inconsistencies between press releases, tax records, and trademark filings create problems. If you issue a press release stating “We started selling X on July 1, 2023,” and your trademark application shows first use as September 2023, that inconsistency could be used against you.

- Keep the first date on which a product shipped or service was rendered clearly documented. Often, companies celebrate their “first dollar”; record it and specifically note the buyer’s location.

- Store specimens in a dedicated folder before filing, so you’re not scrambling during examination. When you file a trademark, you need a specimen. Keep a folder (digital or physical) of current specimens for your mark. Over time, as your branding or labels change, keep samples of each version.

When to Get Professional Help

Consider consulting an experienced trademark attorney before:

- Claiming first use dates in edge cases (foreign sales, test marketing, clinical trials).

- Submitting specimens you’re unsure about.

- Responding to an office action questioning your use.

- Filing applications in an industry you’re unfamiliar with.

An experienced trademark attorney can help you avoid costly mistakes that lead to refusals or cancellations.

Your Next Steps to Trademark Protection Success

Understanding use in commerce requirements is essential, but applying this knowledge to your specific situation (especially when timing and specimen quality determine whether your application succeeds or fails) requires strategic guidance from experienced trademark counsel.

The bottom line: a weak trademark filing makes it easy for competitors to challenge your registration or simply copy your brand with minimal risk. A strong trademark, filed adequately with legitimate use evidence and correct dates, deters infringement and provides enforceable protection that actually holds up when challenged.

Here’s what’s at stake: businesses that rush trademark applications with questionable use claims or improper specimens risk not only USPTO refusals but also the loss of their entire brand investment. With 50% of audited registrations requiring deletion of goods/services and 13% being cancelled entirely, the consequences of cutting corners are real. Competitors who discover weakness in your trademark foundation can challenge your registration, force abandonment, or simply move into your market space knowing your protection is vulnerable.

Take these immediate actions to secure your trademark rights:

- Schedule a Free Trademark Strategy Call with our experienced trademark attorneys to evaluate your specific use situation, review your specimens, and develop a filing strategy that maximizes the likelihood of approval while establishing genuine priority rights.

- Gather and organize your evidence in accordance with the guidelines in this article, including dated invoices, shipping records, website screenshots, and product photographs that document your mark in actual commercial use.

- Document your first-use dates precisely to create a clear record of when you first used the mark anywhere and when you first used it in interstate commerce, ensuring alignment with your business records.

- Evaluate whether use-based or intent-to-use filing makes strategic sense for your situation, considering factors like timing, specimen availability, and competitive threats.

Your trademark is the foundation of brand equity, growing more valuable with every customer interaction. Whether you’re protecting a SaaS platform name, product brand, or service mark, proper trademark registration, supported by evidence of legitimate use, creates defensible rights that support business growth, investor confidence, and market exclusivity.

Working with Rapacke Law Group means you get:

- Get Your Trademark approved or pay nothing. We guarantee it.

- We’re so confident we’ll get your mark approved that if your trademark gets rejected, we’ll issue a 100% refund. No questions asked.

- FREE strategy call with our trademark concierge team.

- Experienced US attorneys leading your registration start to finish.

- One transparent flat-fee covering your entire trademark application process (including office actions).

- Unlimited office action responses.

- Full refund if USPTO denies your trademark application*.

- Full refund or additional searches if your brand has registerability issues (your choice)*.

Don’t let uncertain use, evidence, improper specimens, or incorrect dates undermine your trademark rights. With trademark filings at an all-time high and USPTO enforcement becoming more aggressive, proper guidance from the start protects your brand investment and prevents costly challenges later.

About the Author:

Andrew Rapacke is the Managing Partner at Rapacke Law Group and a Registered Patent Attorney specializing in trademark protection and brand strategy for startups and established businesses. With extensive experience navigating USPTO requirements and use-in-commerce issues, Andrew helps clients secure strong trademark rights that withstand challenges and support business growth.

Connect with Andrew on LinkedIn or follow @rapackelaw on Twitter/X and @rapackelaw on Instagram for trademark insights and IP strategy updates.

To Your Success,

Andrew Rapacke

Managing Partner, Registered Patent Attorney

Rapacke Law Group