By Andrew Rapacke, Managing Partner, Registered Patent Attorney

Most inventors assume filing a provisional patent means keeping their invention completely secret. Then they discover their competitor somehow knew about their technology months before they went public. What happened?

The reality is more nuanced than most patent attorneys explain upfront: provisional patents remain confidential at the USPTO by default, but your invention can still become public through several pathways you need to understand before filing.

Here’s what actually matters: if you file a U.S. provisional on March 1, 2026, that document stays locked in USPTO records. It won’t appear in Google Patents, Patent Center, or any public database. Provisional applications are not part of the public record unless and until they are referenced in a published patent application or issued patent. No competitors, investors, or researchers can access it through official channels. By law, provisional applications are exempt from the 18-month publication rule that applies to regular patent applications.

But, and this is critical, the content of your provisional can eventually become visible if you file a follow-up non-provisional application that gets published. According to USPTO data, inventors filed over 149,310 provisional applications in fiscal year 2023, yet roughly 40% of these provisionals are never converted to non-provisional patents, meaning nearly half remain permanently confidential. For a comprehensive guide on provisional patent strategy and timelines, see our AI Patent Mastery guide.

This guide explains exactly how provisional application confidentiality works, when your content could become public, and how to strategically balance patent protection with the business need to share your invention with investors, partners, and customers. This is especially critical for SaaS founders and tech startups navigating funding rounds while protecting their AI algorithms and software innovations.

Quick Answer: Are Provisional Patents Public or Confidential?

In the United States, provisional patent applications are not published and remain confidential by default. This confidentiality is particularly valuable for SaaS founders and tech startups protecting AI algorithms and software innovations during funding rounds. The USPTO keeps provisional filings secret unless and until they are referenced in a later published patent application or issued patent. Practically speaking, filing a provisional on a new invention will not alert the public or competitors to what you’ve invented. For example, a U.S. provisional application filed today will not appear in public searches or in USPTO databases a year from now; it remains sealed in USPTO records.

Not published: Provisional applications are excluded from the USPTO’s 18-month publication system by statute. Unlike a non-provisional (regular) patent application, which typically publishes 18 months after the earliest filing date, a provisional patent application remains unpublished. It doesn’t matter whether your provisional is pending or has expired; the USPTO won’t disclose it on its own.

Never examined: The USPTO does not examine provisional applications on their merits. They are held on file as evidence of your priority date but are not reviewed for patentability. This means provisionals also aren’t publicly “filed away” in search databases because they don’t progress to any public stage unless tied to a later application.

Accessible only via later filings: The only scenario where the content of your provisional can become public is indirectly: if it’s relied upon and incorporated into a later non-provisional (full) application that gets published or granted. In such cases, the provisional itself can be accessed as part of the public file history of the published patent document.

Not prior art when unpublished: Because provisional applications aren’t published or publicly available, they cannot serve as prior art against third-party patent applications unless the content eventually appears in a published document.

The practical implications are significant: filing a provisional secures your priority date without alerting competitors to your R&D direction. Research shows this confidentiality advantage is why provisional filings increased 26% from 2009 to 2018, with annual filings now exceeding 150,000.

What Is a Provisional Patent Application?

A provisional patent application (PPA) is a U.S. filing under 35 U.S.C. § 111(b) that allows inventors to establish an early priority date without starting the formal examination process. Think of it as a strategic placeholder; it’s like planting a flag that says “I invented this as of today,” giving you time (up to 12 months) to develop your invention further before committing to the full patent application procedure.

When you file a provisional, you immediately get “patent pending“ status for one year. The official USPTO filing fee ranges from $60 to $300, depending on entity size. However, quality professional preparation typically costs several thousand dollars, an investment that ensures proper protection and saves significant time and money during prosecution. The filing requirements are simpler than for a nonprovisional application, which is the next step if you want to pursue patent protection after the provisional period. Notably, you don’t need to include formal claims or an inventor’s oath in a provisional. You do need a thorough written description of the invention (and any necessary drawings) to satisfy patent law’s disclosure requirements, but the document can be less formal in structure; however, the provisional must meet the same requirements for written description and enablement as a nonprovisional application to ensure proper protection. For SaaS and AI inventions, this written description must carefully navigate software patentability requirements. Learn more in our AI Patent Mastery guide.

The USPTO will not examine your provisional application for patentability, and a provisional application can never, by itself, mature into an issued patent.

Here’s how the timing works:

- You submit a provisional on, say, June 10, 2025. That establishes the provisional application’s filing date, which is critical for determining priority.

- That provisional is valid for 12 months. Before June 10, 2026, you need to file a non-provisional (regular utility) patent application if you want to keep pursuing protection. In that complete application, you will “claim the benefit” of the provisional’s date for any content that was disclosed in the provisional.

- The later-filed non-provisional can then eventually be examined and potentially granted. It enjoys the June 10, 2025, priority date for whatever was supported by the provisional. For guidance on this process, consider consulting Andrew Rapacke, a registered patent attorney.

Provisionals are used heavily by startups, universities, and solo inventors for several practical reasons:

Test the waters: It lets you secure a filing date and “patent pending” status while you evaluate market interest before investing in a full patent. You can start talking to customers, partners, or investors with some confidence that you’ve staked a claim. For SaaS founders, this means you can pitch your AI-powered platform to VCs while your core algorithms remain protected.

Lower upfront cost: The filing fee and preparation cost for a provisional are significantly lower than for a non-provisional. This can be a big deal for early-stage ventures. Be careful, though: a poorly prepared provisional can be a false economy, failing to support your later claims and effectively giving you no priority date at all. This is especially critical for AI and software inventions requiring careful claim construction. Learn more about protecting AI inventions with provisional patents in our AI Patent Mastery guide.

Iterative development: During the 12-month window, you can refine prototypes and gather data. If your invention evolves, you can even file additional provisional applications to cover improvements, then roll multiple provisional claims into one non-provisional later. (This is common: you might file one provisional, then a second a few months later for improvements, then a third, and finally file a comprehensive non-provisional claiming all those priority dates.)

Delay costs while deciding: It essentially buys you 12 more months to determine whether the invention merits the cost and effort of full patent prosecution. If you choose not to proceed, the provisional simply expires quietly (and remains secret).

Foreign filing coordination: A U.S. provisional can serve as a priority application for foreign filings under the Paris Convention. This means that if you file foreign patent applications (or an international PCT application) within 12 months, you can claim the provisional filing date in those filings as well. (Foreign patent offices don’t have an exact “provisional” system, but they recognize the U.S. provisional’s date for priority.)

It’s worth noting that the provisional application concept was introduced in the U.S. in 1995 to harmonize with foreign patent systems. Most other countries require you to file a patent before any public disclosure (absolute novelty), and they allow a one-year priority window for foreign filings. The U.S. provisional gives domestic inventors a similar tool to secure a date quickly and then file internationally within a year.

How popular are provisionals? Very popular. U.S. inventors file on the order of 150,000 provisional applications each year in recent years.

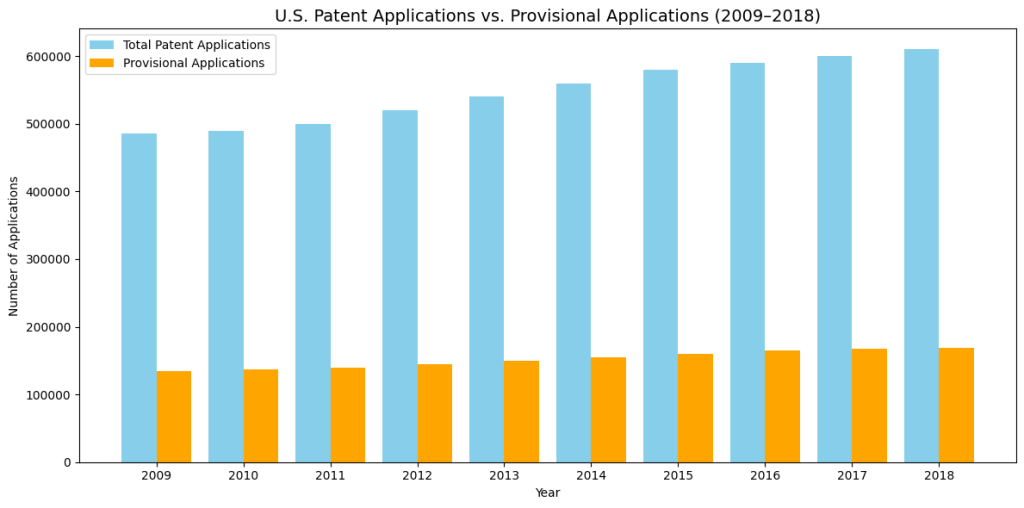

Figure 1: Growth in U.S. Patent Filings, 2009–2018: Total patent applications (blue) steadily increased alongside a notable rise in provisional patent applications (orange), which grew from approximately 134,000 in 2009 to over 169,000 by 2018. This trend reflects increased adoption of provisional filings, particularly among startups and individual inventors seeking early protection with lower initial costs

For instance, the USPTO received 147,339 provisional applications in fiscal year 2022 and 149,310 provisionals in FY 2023. This number has grown significantly over time, increasing by about 26% from 2009 to 2018, indicating that many inventors view provisionals as a useful part of their IP strategy. By contrast, the USPTO receives roughly 600,000 non-provisional utility patent applications per year, so a substantial fraction of inventions start with a provisional filing.

In summary, a provisional patent application is a confidential, temporary patent filing that secures your place in line at the patent office (establishing a priority date) but is not itself examined or published. It gives you “Patent Pending” status and up to 12 months breathing room to decide your next steps.

Benefits of Filing a Provisional Patent Application

Filing a provisional patent application offers inventors a host of strategic advantages that can make all the difference in today’s fast-paced innovation landscape. One of the most significant benefits is securing an early filing date, which is critical in the United States’ first-to-file patent system. By establishing this early priority date, inventors can secure their place in line at the patent office, preventing later filers from claiming rights to the same invention.

A provisional patent application also grants immediate “patent pending” status. This designation not only signals to competitors and investors that you are actively seeking patent protection, but it can also deter would-be copycats. With patent-pending status, inventors can confidently approach potential partners, investors, or customers, knowing their invention is protected from the moment the application is filed.

Another key advantage is the flexibility to publicly disclose your invention after filing a provisional application. Under U.S. patent law, once a provisional is on file, inventors have a 12-month window to publicly disclose, market, or test their invention without jeopardizing their patent rights, as long as a non-provisional patent application is filed within that year. This is especially valuable for startups and entrepreneurs who need to generate buzz, attract funding, or validate their product in the marketplace.

This flexibility is particularly valuable for tech startups that need to demo their SaaS platform at industry conferences or pitch AI capabilities to investors before their patent strategy is fully developed.

Cost is another critical consideration. Provisional patent applications typically require a lower filing fee than non-provisional applications, making them a more accessible entry point for inventors and small businesses. The process is also less formal: provisionals do not require formal claims, an inventor’s oath, or prior art disclosures, which streamlines preparation and reduces upfront legal costs. This lower barrier to entry allows inventors to secure protection early, even as they continue to refine their invention.

For inventions that are still evolving, the ability to file multiple provisional applications is a powerful tool. Inventors can file additional provisionals as improvements or new features are developed, each with its own filing date. When it’s time to file a non-provisional patent application, you can claim priority to one or more of these provisional applications, ensuring that every aspect of your invention is protected from the earliest possible date. This approach is particularly useful in fast-moving fields like software, AI, and consumer electronics, where innovation is continuous.

Provisional patent applications also play a crucial role in international patent strategy. A U.S. provisional can serve as the priority application for foreign filings under the Paris Convention, giving inventors up to 12 months to file in other countries while maintaining the original U.S. filing date. This can be a significant advantage when seeking patent protection in multiple jurisdictions. This approach is particularly useful in fast-moving fields like software, AI, and SaaS platforms, where innovation is continuous, and features evolve rapidly in response to user feedback and market demands.

Importantly, provisional patent applications remain confidential and are not publicly accessible through the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) unless they are referenced in a later-published non-provisional application. This means inventors can file provisional applications without fear that their invention will be disclosed to the public or competitors before they are ready.

In summary, filing a provisional patent application is a smart, cost-effective way to secure an early filing date, establish patent pending status, and protect your invention. At the same time, you develop, test, and market it. By leveraging the flexibility to file multiple provisional applications and claim priority in later non-provisional filings, inventors can build a robust foundation for patent protection—both in the U.S. and internationally—while keeping their innovations confidential until the right time. Understanding these benefits empowers inventors to make informed decisions and maximize the value of their intellectual property.

Are Provisional Patent Applications Published or Publicly Accessible?

No: the USPTO does not publish provisional patent applications. They remain secret unless a later published application reveals them. Let’s break down what this means:

- When you file a provisional, it’s assigned a serial number and stored in the USPTO’s internal records. It is not released to the public or indexed in any public database as a standalone document. Even if you search the USPTO Patent Center or Google Patents by inventor name or keywords, you will not find provisional applications.

- This is in sharp contrast to non-provisional (regular) applications, which are published by default 18 months from the earliest priority date. For example, if you file a non-provisional on January 5, 2026 (without a non-publication request), the application will typically be published around July 5, 2027 (18 months later), and anyone can read its contents at that point. But the provisional itself? It stays hidden, unless it’s part of that application’s history.

- Filing a provisional is thus a way to secure a filing date without disclosing the invention to competitors or the public. Your claimed subject matter remains between you and the patent office for the time being. Competitors won’t be tipped off to what you’re working on by the mere fact that you filed a provisional.

An important legal point: A provisional by itself is not considered “prior art” against someone else’s later patent applications, because it’s not published or publicly available. Prior art generally must be publicly disclosed. Your provisional only becomes prior art once its contents are published through a non-provisional application or patent that you file later (more on that soon). In other words, if you file a provisional and never follow up with a published application, the information in that provisional never enters the public domain to be used against others’ patent filings.

Consider a concrete example: A SaaS founder files a U.S. provisional on May 1, 2026, describing a new AI-powered predictive analytics engine for enterprise customers. They spend a year developing the product and gathering beta user feedback, but ultimately decide not to pursue a patent or file a non-provisional application. On May 1, 2027, the provisional expires and is abandoned. What happens to that disclosure? It remains permanently secret. It will never be visible to the public, never appear in patent searches, and never be cited as prior art against anyone else’s patent claims. The USPTO essentially acts as a vault; it keeps the invention confidential on file, and since no later-published patent emerged from it, the public never gains access to those details.

This privacy advantage is significant. Unlike a published patent application (which telegraphs your R&D to the world), your provisional filing doesn’t tip off competitors to what you’re working on. Startups often value this, as it allows them to claim “patent pending” and secure funding or partnerships without revealing technical specifics to rivals.

When Can the Content of a Provisional Become Public?

While the USPTO doesn’t publish the provisional document itself, its content can become public indirectly if it’s carried over into a later published application.

Here’s the typical scenario: Suppose you file a provisional on March 15, 2026. Then, before March 15, 2027, you file a later-filed nonprovisional application that claims priority to the provisional. That nonprovisional will usually be published 18 months from the provisional application’s filing date (since the provisional was the earliest filing). In this case, around September 15, 2027, the USPTO will publish your nonprovisional application (18 months after March 15, 2026), and that publication will include whatever text and drawings you carried over from the provisional. Figure 2: Patent Filing Timeline: Visualizes the 12-month window to file a non-provisional after a provisional, followed by the 18-month publication delay—highlighting when patent content becomes public.

Essentially, the things you disclosed in the provisional become public as part of the published nonprovisional patent application.

A few notes on this process:

- The provisional itself isn’t separately published at 18 months; rather, the later application is. However, because the later application usually copies or incorporates the provisional’s disclosure, the effect is the same: the world now learns what was in your provisional.

- The USPTO typically makes the original provisional filing available in the electronic file wrapper of the non-provisional application once the non-provisional is published or issued. For example, on the USPTO’s Patent Center or Public PAIR system, if you look up the published application, you might see the provisional application PDF in the “Image File Wrapper” as part of the history. This is because the provisional is now part of the official record relied on for priority. Important: This only happens after the related application is public. The USPTO won’t release your provisional file on its own. But if you tie it to a published patent application, it becomes accessible as supporting material.

- If no non-provisional is filed (or if none of the non-provisionals you file ever get published), then the provisional’s content remains permanently confidential. For instance, if you abandon the invention or keep the project secret and let the provisional lapse, it stays locked away. The USPTO will not, out of the blue, publish abandoned provisionals later.

To summarize: Your provisional’s details enter the public domain only when you want them to, i.e., when you move forward with a regular patent filing that gets published. You are in control of that timeline (with the default being 18 months after your earliest filing). If you never move forward, the information never goes public via the USPTO.

Non-Publication Requests and Extended Secrecy

U.S. patent law provides an additional tool for maintaining confidentiality: the Non-Publication Request. Usually, all U.S. non-provisional applications are published at 18 months (unless they’re already granted or withdrawn by then) as explained above. But an applicant can request non-publication under 35 U.S.C. § 122(b)(2)(B)(i) at the time of filing a non-provisional if they certify that they will not file foreign applications that require publication.

What does this do? If you file a non-provisional with a proper non-publication request, the USPTO will not publish your application for 18 months. It will remain confidential within the USPTO until the patent issues (or the application is abandoned). This effectively keeps your invention confidential for longer, or indefinitely if no patent is granted.

How is this related to your provisional? Well, if your non-provisional isn’t publishing at 18 months, then the content from your provisional isn’t being revealed either (since it would have been shown through that publication). In other words, a non-publication request on the non-provisional allows the provisional’s information to stay non-public as well, at least until a patent issues.

However, there are a couple of catches and considerations:

If you later decide to file foreign patents (for example, file in Europe or China) after initially opting out of publication, you are legally required to notify the USPTO and withdraw the non-publication request. You typically must do this within 45 days of filing the foreign application. Once you cancel the request (or if you fail to timely notify, in which case your U.S. application is deemed abandoned), the USPTO will promptly publish your U.S. application. In other words, you can’t keep a U.S. application secret while seeking foreign patents; international transparency is required.

Non-publication requests are most useful if you intend to file only in the U.S. and want to maintain secrecy until a grant is awarded (or if you abandon the application). This can be a strategic choice in some cases. For example, if you’re not sure whether you want to disclose the invention unless you can actually get a patent issued, or if you believe keeping the application secret longer gives you a competitive edge. Some inventors choose this route so that if the application doesn’t look allowable, they can abandon it without ever revealing the invention.

Statistically, relatively few applicants use non-publication requests.

Figure 3: Patent Publication Preferences Among U.S. Applicants: Based on data from Graham & Hegde (Science, 2015), approximately 87% of patent applicants allow their applications to be published by the USPTO at the standard 18-month mark, while only 13% file non-publication requests. This shows that most inventors—regardless of size or sector—prefer early disclosure to extended confidentiality.

Studies have found that only about 10 to 15% of eligible U.S. applications opt out of publication. The vast majority of inventors (even small entities) choose the standard publication route, often because they plan to file internationally or don’t mind the 18-month publication period. So, non-publication is a niche strategy, but a useful one in the right circumstances.

If you do file a non-publication request, remember that it applies to the non-provisional application. Your provisional was never going to be published anyway. The request just ensures the next-stage application also stays under wraps.

In summary, a Non-Publication Request can extend the confidentiality of your provisional’s content beyond 18 months, but only if you stay U.S.-only in your filings. The moment you venture abroad, or if you want to enforce a patent, publication will happen. This mechanism is mainly about timing: it lets you delay disclosure and, if you never get a patent, potentially never disclose at all.

What Happens If You Don’t File a Non-Provisional After a Provisional?

A provisional application is temporary. By design, it expires (becomes abandoned) 12 months after its filing date, unless it’s used as the basis for a non-provisional or international (PCT) application within that time. There is no such thing as extending a provisional’s life beyond 12 months (with one minor exception we’ll mention shortly).

So, let’s say you filed a provisional on August 20, 2026. If by August 20, 2027, you have not filed a corresponding non-provisional (or PCT) that claims priority to it, the provisional will be automatically abandoned. You lose the benefit of that filing date for your invention going forward. You cannot later resurrect that provisional or reclaim that date; the opportunity is gone. (Filing a new application later would get a new date, but any disclosures you made in the meantime might count against you.)

Now, critically, if you don’t follow up with a non-provisional, the provisional remains confidential and “invisible” to the public. It doesn’t suddenly become published at the 12-month mark. It simply expires in the USPTO’s internal system. As we emphasized earlier, an unpublished, abandoned provisional is not available to the public and does not count as prior art against others.

To paint the picture: many inventors file provisionals and then decide not to proceed with a patent for any number of reasons (feasibility issues, funding problems, pivoting to a different idea, etc.). It’s very common. In fact, studies indicate roughly 40% of provisional applications are never converted into non-provisional patents. These filings quietly lapse after a year. The inventions disclosed in them remain trade secrets in effect, known only to the inventors and the USPTO. If those inventors never publicly revealed the ideas elsewhere, it’s as if the provisional never existed from the public’s viewpoint.

One caveat: Even though the provisional itself stays secret, consider what you do during that provisional year. If you make any public disclosures of the invention, like selling the product, publishing a paper, or presenting at a conference, those actions could have legal consequences for patentability (more on that in the next section). The key point is that the USPTO’s confidentiality remains, but your own actions can still impact the situation.

Now, about that narrow exception: U.S. law provides a slight grace if you miss the 12-month deadline. Under 37 C.F.R. § 1.78, in certain circumstances, you can petition for a 2-month extension of the deadline to claim priority (up to 14 months from the provisional’s date). This is usually used if someone unintentionally misses the deadline to file the non-provisional. The petition requires a fee and an explanation of unintentional delay. If granted, your later non-provisional can still benefit from the provisional date. Significantly, this doesn’t extend the provisional’s life or change its confidentiality; it’s purely a legal fix for the subsequent application’s benefit. After 14 months, there’s no remedy; the provisional date is lost for good.

Bottom line: If you don’t file a non-provisional (or PCT) in time, your provisional application will expire and be gone. The document remains secret (unless it was later referenced in a public source, which, for the sake of this argument, it wasn’t). You can walk away knowing the USPTO didn’t publicly disclose your idea. But you also no longer have any patent-pending status or a priority date locked in after that point.

Impact on Prior Art and Third-Party Filings

For example, let’s say you filed a provisional in January 2026 and showcased your invention at a trade show in June 2026 (public disclosure). Under US law, there is a 12-month grace period for inventor disclosures, so you must file a non-provisional application within one year of your public disclosure to maintain your rights in the U.S. If you do not file a non-provisional by January 2027, then as of that date your provisional application will expire. If you then attempt to file a new patent application later in 2027, your June 2026 disclosure would likely count as prior art against you (outside the grace period), preventing you from obtaining a patent in the U.S. and definitely barring you in Europe and most countries with no grace period. Meanwhile, that June 2026 disclosure was public, so if a competitor saw it and filed something before you did, that could complicate matters as well.

Does Filing a Provisional Patent Let You Safely Go Public With Your Idea?

One significant advantage of the U.S. system is the inventor-friendly “grace period.” Simply put, if you (the inventor) disclose your invention publicly, you have up to 12 months to file a U.S. patent application without that disclosure counting against you. Filing a provisional patent application is a strategy to go public with less risk.

Here’s how many startups and inventors approach it:

- File a provisional before any public disclosure of the invention. This locks in a priority date.

- Immediately after filing, you can say “patent pending” and start sharing your idea. For example, showcase it at CES in January, launch a crowdfunding campaign, or pitch to investors, without fear that any of these will jeopardize your U.S. patent rights. Your provisional filing date predates these disclosures.

- Within 12 months of that provisional, file the non-provisional application (or a PCT). This converts that early stake into a complete patent application, claiming the benefit of the provisional date.

By doing this, you “safely” go public in the U.S. sense. Your own disclosure won’t be used against your U.S. patent application. In patent law terms, the disclosure is excluded from prior art under 35 U.S.C. § 102(b)(1) as long as the patent application is filed within a year.

For example, suppose you filed a provisional on October 3, 2026. In January 2027, you unveil your invention at a major tech expo, generating press and interest (a public enabling disclosure). Under U.S. law, you have until October 3, 2027, to file a non-provisional and still get your patent (the provisional’s date protects you, and the grace period exempts that January disclosure from knocking out your patent). If you meet that deadline, the USPTO will not cite your own demo against you.

However, and this is crucial for global rights, many foreign jurisdictions do not offer such a grace period. Countries such as those under the European Patent Convention (EPC) and China operate under a strict absolute novelty rule. This means any public disclosure of the invention before you file a patent application invalidates potential patent rights in those countries. The only exceptions are minimal (e.g., a 6-month grace for disclosures at officially recognized exhibitions or due to abuse, in Europe). So, in our example, publicly demonstrating the invention in January 2027 would likely forfeit patentability in Europe unless you had actually filed a patent application before that demo (the provisional in October 2026 covers the U.S., but for Europe, if you didn’t also file something like a UK or EPO application by then, you’re out of luck).

This is why you’ll often see advice: if foreign patents matter to you, do not publicly disclose before filing. A U.S. provisional can serve as that initial filing internationally (via the Paris Convention), but you must still file overseas within 12 months. If you disclose first and only have a U.S. provisional, foreign jurisdictions might not honor the grace period.

Strategically, many inventors follow this pattern:

- File a provisional immediately before the first public disclosure. Even a day before is fine; the important part is that the patent filing happens before you go public.

- Use the 12-month window after that to gather feedback, attract investment, and further develop the technology under the banner “patent pending.”

- Just before the provisional’s 12 months are up, decide where to file full applications: at least in the U.S. (convert the provisional to a non-provisional) and possibly internationally (via a PCT application or direct national filings) to cover key markets.

This way, you maximize both: you get to engage with the market early (important for startups proving traction or scientists publishing research) and still preserve patent rights.

To be clear, a provisional itself doesn’t give you an enforceable right to stop others; it’s the subsequent patent that will do that. During that provisional year, if someone outright copies your product and sells it, you cannot sue for infringement until you have an issued patent. But the “Patent Pending” notice is not useless; it can deter some would-be copycats and shows investors you are serious about IP. Moreover, if you proceed to a patent, the patent (once issued) can be enforced retroactively against infringing activities that occurred after publication of your non-provisional application (via provisional rights under 35 U.S.C. § 154(d)), though that’s a limited remedy.

One more scenario to watch: because your provisional stays secret, a competitor might independently invent and file a patent on a similar idea during your provisional year. If they file a non-provisional and it is published before your application, neither party would know about the other due to the secrecy. In a first-to-file system, who wins? If your provisional predates their filing, you will win on priority for the overlapping subject matter, provided that you file your non-provisional on time. Your application can cite the provisional date. Their application, however, might be prior art to any of your improvements disclosed after it was filed. This is a complex scenario, but the takeaway is that filing provisional early protects you from those who come after you, but not from those who might file before you. So don’t wait unnecessarily; being the first to file is crucial under current law.

Confidentiality vs. Marketing: Balancing the Two

Inventors often face a tension: you want to keep your “secret sauce” confidential until you secure patents, but you also need to market your invention to customers, to investors, to partners, especially in the startup world, where speed matters. How do you balance the two?

Filing a provisional gives you a tool to balance these concerns:

- After filing, you have some peace of mind knowing that your core invention is documented with the USPTO and has a priority date. You can publicly claim “patent pending.” This status can be valuable in business negotiations. In fact, many sophisticated companies or investors require patent-pending status before discussing deals. It shows that you have taken steps to protect your IP (and it protects them from later being accused of stealing your idea since you’ve established record ownership).

- However, patent pending does not mean you should reveal everything. An innovative approach is to avoid disclosing more details publicly than what you included in your provisional. If your marketing materials, pitch decks, or product demos start showcasing new features or improvements that weren’t covered in your provisional filing, you could be jeopardizing your ability to protect those new aspects. Why? Because those undisclosed features, once public, could be used as prior art against a later-filed application covering them (since you wouldn’t have an earlier priority date for those features).

- Many companies handle this by sequenced filings. Example: File a first provisional on the core concept (covering the base functionality). The first provisional application establishes the initial priority date, and subsequent provisional applications can be filed to protect ongoing advances or improvements as they are developed. This strategy helps secure the earliest possible priority date for each development milestone, which can be crucial for later patent filings and protecting the invention’s novelty. Under US patent law, inventorship is determined by contribution to the conception of at least one claim in the application. Repeat as needed. Finally, when it’s time, file one non-provisional application that claims priority to all those provisionals (a practice that U.S. law allows, as long as the non-provisional is filed within 12 months of the earliest provisional). This way, by the time you’re really going public in a big way (say, a full product launch), you’ve already filed on every key aspect you plan to disclose. You maintain coverage for each disclosed improvement. This strategy is frequently used by SaaS startups and in fast-moving fields like AI, where development is rapid.

- During interactions with outsiders (like potential licensees or investors) before you have patent filings, NDAs (non-disclosure agreements) are a common tool. But NDAs have limitations: they can be breached and hard to enforce. Once you’ve filed a provisional, you have an extra layer of protection because even if someone leaks your info, your filing date is secure. In fact, many professionals see a provisional as stronger than an NDA in some respects: an NDA relies on trust and legal enforcement, whereas a provisional gives you legal priority and a potential patent right to assert later.

- It’s also worth noting that patent-pending status can be a business asset beyond its deterrent value. It can impress investors (patented or patent-pending technology often increases a company’s valuation or at least signals innovation). It can be leveraged in marketing (“our unique patented process” has a nice ring to it). And even though a provisional is not a granted patent, having that application can allow you to say you have intellectual property in the pipeline. Some companies even list provisional applications in their pitch or on their balance sheets as part of their IP portfolio (with appropriate caveats).

The balance in practice: Share enough to achieve your business goals (fundraising, partnership, market buzz), but protect yourself first by filing, and don’t overshare beyond what you’ve filed. If you must disclose new information (such as a prototype upgrade), consider filing an additional provisional application beforehand. It’s a cat-and-mouse game of timing, but it can be managed with planning.

One more piece of advice: coordinate with a patent attorney when planning significant disclosures. They can often draft and file a quick supplemental provisional on short notice if you realize you’re about to spill some unpatented beans. It might cost a bit, but it’s worth it for essential innovations. Remember, any information that leaves the confidential realm could prevent you from obtaining a patent on that information later, unless you have a prior filing.

In sum, provisional applications and smart IP strategy allow you to engage in the marketplace while preserving patent rights. Use them as part of an overall plan: file early, update often, and be mindful of what you disclose when. For more on building a comprehensive IP strategy for SaaS companies, check out our SaaS Patent Guide 2.0.

Frequently Asked Questions About Provisional Patents and Public Access

Q1: Are provisional patent applications publicly accessible?

A: No, not by default. Provisional applications stay confidential at the USPTO and are not published in patent databases. You generally cannot see someone else’s provisional application. The only exception is if the provisional is later identified in a published patent filing (for example, referenced in a published non-provisional or issued patent). In that case, the provisional might be available in the public file history. But if a provisional was filed and never followed by a published application, it remains permanently hidden. In short, you can’t go look up other people’s provisionals through any normal means.

Q2: How long does a provisional application remain confidential?

A: For its entire life and beyond, essentially forever, unless it’s used in a later published patent. A provisional application filed on, say, April 2, 2026, will remain confidential for 12 months, and even after it’s abandoned on April 2, 2027, it will remain unpublished in the USPTO vault. The content becomes public only if it is disclosed through another publication (such as a 2027 patent application that quotes it). Otherwise, the USPTO preserves it in confidence indefinitely per law. (There are provisions for national security cases or the like, but those are rare and not typical.)

Q3: Can I see someone else’s provisional patent application?

A: Generally, no. Provisional applications are not open to public inspection. The only time you might indirectly see one is if you look at a published patent application or issued patent that claims priority to it, in which case the provisional document may be available as part of that file. For example, if Inventor A files a provisional, then files a non-provisional that gets published, you could retrieve Inventor A’s provisional from the USPTO’s image file wrapper for that published application. But you cannot see any provision that isn’t linked to a published outcome. So if someone files a provisional and never files anything after, it’s invisible to you.

Q4: Does filing a provisional stop others from filing their own patents on the same idea?

A: It secures your priority date, but it doesn’t physically stop others from filing. Because your provisional is secret, another inventor could independently come up with the same concept and file their own patent application. They won’t know about your filing. However, if you promptly file a non-provisional application while your patent application is pending, your earlier provisional filing date can be used during examination to preempt their claims (you’d have priority). Additionally, once your non-provisional publishes or your patent issues, then your disclosure is public and can serve as prior art against others. So, the provisional itself is a quiet placeholder; it’s not a public deterrent until you convert it into a published patent application. Think of it this way: a provisional is a private stake in the ground, not a fence. The “fence” that blocks others (enforceable rights and prior art effect) comes later with the published/issued patent.

Q5: Do I need to include formal patent claims in a provisional?

A: No, formal claims are not required in a provisional application. This is one of the key differences from a non-provisional. A provisional is a disclosure of an invention, not a set of legally numbered claims. In fact, the USPTO will not even accept claims fees or examine provisional claims. That said, describe your invention as fully as possible, covering various aspects and alternatives, so that you have support for claims you might write later. Some practitioners do include one or more informal “claims” in the provisional for completeness, but it’s not mandatory. What is compulsory is that the provisional contains a written description that enables the invention, meeting the requirements of 35 U.S.C. § 112(a) (basically, teach someone skilled in the art how to make and use the invention). You also need to provide any essential drawings and a cover sheet identifying it as a provisional (plus pay the filing fee). In summary: no oath, no claims, no prior art listing needed, but don’t skimp on the technical details and scope in the write-up.

Q6: What if I want to file multiple provisional applications for incremental improvements?

A: You absolutely can. It’s common to file, for example, an initial provisional and then follow up with one or more additional provisionals as your R&D progresses. Each one gets its own filing date. When you later file a non-provisional, you are allowed to claim priority to multiple provisionals (within 12 months). This can give you various priority dates for different parts of your invention. The USPTO will treat each claim in your non-provisional as having the date of whichever provisional first supported that claim. This strategy is helpful if, say, you invent a basic device in January (provisional 1), improve it in June (provisional 2), and add a new feature in September (provisional 3). Your final patent application could be filed in January next year, claiming priority in Jan, June, and Sept for the respective pieces. All those provisional filings remain confidential, by the way, until the non-provisional publishes. This “chain of provisionals” approach is commonly used by inventors who continue to iterate during the 12-month window; it helps ensure no new development goes unfiled before disclosure. Just keep track of the dates and make sure to file the non-provisional within 12 months of the earliest provisional (not 12 months from the last one). Also, it may increase costs slightly (each provisional has a filing fee and attorney time), but it may be worth it for robust protection.

Q7: If my provisional stays secret, what happens if someone else files a patent on a similar idea after I filed my provisional?

A: This touches on the first-to-file system nuances. If someone else files a non-provisional patent application on a similar invention after your provisional filing date but before you file your non-provisional, there could be a conflict. You have the earlier date, but you haven’t publicly disclosed it yet. In the patent examination process, when your application eventually comes up, you can cite your provisional date to “swear behind” the other filer (assuming your provisional indeed described the overlapping invention). You would get priority for what you invented first. However, if the other party’s application got published, it could become prior art against aspects of your invention that were not covered in your provisional. These scenarios can become complicated (sometimes leading to derivation proceedings or interference-like situations under pre-AIA rules if dates were extremely close). The main thing to know is that your earlier provisional generally wins priority based on what it fully discloses. Still, it’s far cleaner to beat competitors by filing the non-provisional quickly. Don’t let others get a six-month head start on you with the full application if you can help it. If you discover that someone else has a similar patent application pending, definitely consult a patent attorney about how to proceed.

Q8: What does “patent pending” really do for me?

A: “Patent pending” simply means you have applied for a patent (provisional or non-provisional) and that application is in progress. The phrase can be put on products or used in literature to warn others that you have a filing. Legally, patent pending does not confer any enforceable rights; you can’t sue anyone for infringement while your application is pending, because there’s no patent yet. However, as mentioned, it’s a deterrent and signals seriousness. It can deter some would-be infringers from blatantly copying you, since they know a patent might issue, and they’d be liable. It can help secure funding or media attention by suggesting a level of innovation. Once your non-provisional is published, you also have the option (under U.S. law) to get a reasonable royalty from an infringer for the period between publication and patent issuance if the infringer had actual notice of the published application (this is under 35 U.S.C. § 154(d), “provisional rights”; confusing name aside, it’s about published applications, not provisional filings). But that’s rarely invoked and requires the issued claims to be substantially identical to those that were published. In essence, patent pending is a phase, a crucial one, but its power is mostly in potential. It’s the alarm sign, not the actual guard dog.

Q9: If I decide not to pursue a patent after a provisional, is there any harm?

A: Not particularly, aside from the time and money spent filing it. The provisional will just lapse and stay secret. You haven’t published your idea through the USPTO. The only “harm” is that you have no patent protection on that invention going forward. If you had publicly disclosed the invention, you might also have started the clock on losing foreign rights, or even U.S. rights, after a year. But assuming you kept everything quiet and simply decided the invention wasn’t worth patenting, the provisional’s expiration just means you no longer have a patent pending. One consideration: if you later change your mind (after 12 months) and want to patent that invention, you’ll have to start over with a new application and new filing date, and any of your own intervening disclosures or others’ developments could count against you. So, think carefully before letting a promising provisional die. Many inventors file provisional applications just to buy decision time, which is precisely what they’re for.

Q10: Should I use an NDA in addition to filing a provisional when talking to investors or partners?

A: Using an NDA (Non-Disclosure Agreement) can still be a good idea when feasible; a belt and suspenders approach. A provisional protects your concept in terms of patent rights (establishes filing date), but an NDA can protect against unauthorized use or sharing of your information in general. Many investors, however, will not sign NDAs, especially VC firms, because they hear so many pitches. By having a provisional on file, you’ve already mitigated a big chunk of risk: you can freely share the content in your provisional, knowing your patent rights on that content are preserved. The NDA would further bind the other party not to use or disclose your information. If they won’t sign, at least you have the patent pending. In summary: Provisional = patent strategy (offensive/protective for future rights), NDA = confidentiality strategy (try to prevent leaks/misuse now). They aren’t mutually exclusive; they tackle different aspects of IP protection.

Your Next Steps to Provisional Patent Success

Understanding provisional patent confidentiality is crucial, but the quality of your provisional filing determines whether it actually protects you or creates a roadmap for competitors. Weak provisional patents that fail to describe your invention adequately give you no priority protection, and worse, they can signal your R&D direction to competitors who file stronger applications first.

The bottom line: Weak provisional filings leave gaps that competitors exploit—and in our first-to-file system, filing a deficient provisional is often worse than not filing at all because it starts your 12-month clock without actually securing protection. Strong provisional patents, prepared by experienced patent attorneys using Rapacke Law Group’s proprietary approach, thoroughly document every aspect of your invention with the technical precision and legal strategy required to support strong claims later. This creates an impenetrable foundation for your IP portfolio, deterring competitors and attracting investors.

Here’s what’s at stake: Every day you wait to file, you risk someone else filing first in our first-to-file system. Every feature you disclose publicly without provisional coverage becomes potential prior art against your own patent. Every investor conversation without “patent pending” status signals vulnerability to competitors. For SaaS founders and tech startups, the window between invention and market launch is shrinking, and so is your opportunity to secure protection.

Take these immediate action steps:

- Schedule a Free IP Strategy Call with Rapacke Law Group to evaluate your invention’s patentability, map your 12-month provisional timeline, and create a protection strategy aligned with your business goals and funding milestones.

- Review your upcoming disclosures: Identify any product demos, investor pitches, conference presentations, or website launches in your calendar. You need to file a provisional protection BEFORE these events to preserve your rights.

- Assess your current R&D: document which features are in use today and which are in development. This determines whether you need one comprehensive provisional now or a series of provisionals to cover iterative improvements.

- Map your international strategy: If you plan to expand globally, understand that your 12-month provisional clock also applies to foreign filing deadlines. Planning now prevents costly mistakes later.

Your competitors aren’t waiting to file patents, and in today’s first-to-file system, the early filer wins. Whether you’re protecting AI algorithms, SaaS platforms, or emerging tech innovations, the provisional patent you file today becomes the foundation for every strategic advantage you build tomorrow. Proper provisional patent protection isn’t just legal paperwork; it’s the difference between owning your market and watching competitors patent your innovations.

The RLG Guarantee for Provisional Patents:

- FREE strategy call with the RLG team to assess your invention and filing timeline.

- Experienced U.S. patent attorneys lead your application start to finish: no outsourcing, no junior staff.

- One transparent flat-fee covering your entire provisional patent application process (including any office actions)

- Full refund if USPTO denies your provisional patent application*

- Complete refund or additional searches if your application has patentability issues: your choice*

*Terms and conditions apply. Schedule your free consultation to discuss your specific situation.

About the Author:

Andrew Rapacke is the Managing Partner at Rapacke Law Group and a Registered Patent Attorney specializing in software patents, AI patents, and IP strategy for tech startups and SaaS companies.

Connect with Andrew on LinkedIn or follow RLG on Twitter/X (@rapackelaw) and Instagram (@rapackelaw) for daily IP insights.

To Your Success,

Andrew Rapacke

Managing Partner, Registered Patent Attorney

Rapacke Law Group