Most inventors approach provisional patents backwards. They rush to file a bare-bones application, thinking it’s just a placeholder, only to discover 12 months later that their skeletal disclosure can’t support the claims they actually need. The provisional then becomes worthless—and in a first-to-file system, that timing gap can mean losing patent rights entirely.

Here’s what the data reveals: According to the USPTO’s FY 2023 Workload Tables, the USPTO received ~149,000 provisional patent applications, versus 594,143 utility applications—roughly one provisional for every four utility filings. This ratio highlights the relationship between provisional filings and the subsequent utility patent application process. Yet approximately 50% of these provisionals are never converted into full applications, often because inventors either weren’t ready to proceed or discovered their initial filing was too incomplete to be useful.

Startups with early patent filings are 6.4 times more likely to secure venture capital funding than those without IP protection. That “patent pending” status isn’t just legal positioning—it’s a business signal that can determine whether your company gets funded or overlooked. For SaaS founders and tech startups developing AI algorithms, machine learning systems, or innovative software solutions, this becomes even more critical—investors want to see that your core technology has defensible IP before they commit capital. In the U.S., utility patent applications are the standard route for securing enforceable rights and building a strong IP portfolio.

But here’s the critical mistake: treating a provisional as a quick formality rather than a strategic foundation. The quality of what you file in that initial application directly determines whether you can claim priority 12 months later. Miss key details, and you’ll face a choice between abandoning claims or losing your early filing date to competitors who filed between your provisional and non-provisional applications. There are multiple ways the patent prosecution timeline can be affected by the quality of the initial filing, including delays, rejections, or loss of rights.

This guide breaks down the provisional patent timeline with specifics you won’t find in USPTO guidance: the actual conversion rates by technology sector, the real pendency times based on 2024 data, and the strategic decisions that separate successful provisional filers from those who waste their $300 filing fee. The data and strategies discussed are particularly relevant for those planning to file utility patent applications and seeking to secure utility patents.

What a Provisional Patent Actually Does (And Doesn’t Do)

A provisional patent application is an initial, temporary patent filing that lets you lock in an early filing date without the formalities of a full patent application. Unlike a standard (non-provisional) application, a provisional application does not require any patent claims, oath/declaration, or prior art disclosures. It is also never examined by the patent office on its merits.

The objective function: A provisional application is a 12-month option on patent rights. You’re essentially buying time to develop your invention, test the market, and prepare a stronger non-provisional application, all while holding an official USPTO filing date that can block later filers from claiming the same invention. For software developers and AI innovators, this year is invaluable for refining algorithms, gathering user data, and demonstrating product-market fit to investors.

What it absolutely doesn’t do:

- Grant any enforceable rights. A provisional application will never become an issued patent; it simply expires after one year. During that year, you can mark your product “patent pending,” but you can’t sue anyone for infringement because you don’t have a patent yet.

- Chain to other applications for an extended time. Provisional applications cannot claim the benefit of any prior-filed application, whether foreign or another provisional. Each provisional stands alone on its 12-month clock.

- Automatically protects you. The “patent pending” label carries no legal teeth; it’s a psychological deterrent only. Competitors can copy your invention during the provisional period, and you’ll have no recourse unless you eventually obtain an issued patent with claims covering their product.

The U.S. introduced provisional applications in 1995 under the GATT Uruguay Round Agreements to provide a lower-cost first filing and give U.S. inventors parity with foreign applicants who had a one-year “priority year” under the Paris Convention. Before this, U.S. inventors filing abroad faced a strategic disadvantage: they had to file expensive applications in every country simultaneously or risk losing foreign rights.

The provisional changed the game: File once in the U.S. for $300 (or as little as $60 for micro-entities), get “patent pending” status immediately, and preserve the right to file internationally for 12 months while still claiming your original U.S. date.

Why Half of All Provisionals Die After 12 Months

Research analyzing provisional filings from 2005 to 2020 found that approximately 50-52% were converted into regular applications, meaning roughly half were abandoned. But this statistic masks significant variations by technology sector.

Higher conversion rates occur in computers/communications and chemical/medical sectors, where filing date sensitivity matters most. In fast-moving software and pharmaceutical fields, being first to file can determine whether you get patent protection or find yourself blocked by someone who filed days earlier. For AI and machine learning innovations, where competitors are racing to patent similar algorithmic approaches, this timing advantage becomes absolutely critical.

The reasons provisionals go abandoned fall into three categories:

1. Strategic abandonment (the good kind). The inventor used the 12-month window to determine that the invention wasn’t commercially viable, that the market was already saturated, or that pursuing a trade secret strategy made more sense. In these cases, the provisional served its purpose; it bought time to make an informed decision without an expensive commitment.

2. Insufficient disclosure (the costly mistake). The provisional was filed hastily with incomplete details. When drafting the non-provisional 11 months later, the inventor realized they couldn’t claim what they actually built because the provisional only vaguely described the concept. Rather than file a non-provisional with a later effective date for key claims, they abandoned everything.

3. Resource constraints. The $10,000–$20,000 required for a properly drafted non-provisional utility patent application simply wasn’t available. Many independent inventors file provisional applications optimistically, only to find they can’t secure funding or justify the expense when the deadline arrives.

About 15–18% of U.S. provisionals are used as priority for European Patent Office filings, indicating that international strategy plays a significant role in conversion decisions.

The First-to-File Reality: Why Filing Date Determines Everything

Since 2013, the USPTO has operated under a first-to-file system, in which patents are awarded to the first inventor to file, not necessarily the first to invent. This fundamentally changed patent strategy.

Real-world scenario: You develop a novel software algorithm in January 2025. You spend six months perfecting it before filing a provisional in July 2025. Meanwhile, a competitor independently develops something similar and files their provisional in May 2025. When you both file non-provisional applications and the patent office discovers the overlap, the competitor wins priority—even if you can prove you invented first.

The lesson: In high-competition technology areas, speed matters enormously. The provisional patent’s key value is establishing that filing date as quickly as possible, then using the 12-month window to strengthen the application rather than delay initial filing. For more insights on protecting software innovations, see our SaaS Patent Guide 2.0.

The U.S. does maintain a 12-month grace period: if you (the inventor) publicly disclose your invention, you have one year to file a patent application without that disclosure counting as prior art against you. But relying on this is dangerous for two reasons:

- International rights evaporate. Most foreign countries have absolute novelty requirements; any public disclosure before filing destroys patentability abroad, grace period or not.

- Competitor disclosures don’t wait. If someone else publishes or files a patent application about the same invention during your grace period, that can still block your patent.

The smarter strategy: File a provisional before any public disclosure, then present/publish during the 12-month pendency, knowing you’re already protected for both U.S. and international rights (assuming you file internationally within 12 months).

What $300 Actually Buys You: Cost Analysis

The USPTO filing fee for a provisional application is $300 for large entities, $150 for small entities, and $75 for micro-entities. Compare this to non-provisional utility applications: filing, search, and examination fees total over $1,500 for large entities alone, plus legal fees that typically run $8,000–$15,000 for professional preparation.

But here’s what many inventors miss: the provisional filing fee is only a tiny fraction of the real cost.

If you’re preparing the provisional properly, with sufficient detail to support future claims, you’ll likely spend several thousand dollars on attorney time. A well-drafted provisional can cost $3,000–$8,000 in legal fees, depending on technical complexity. The alternative is filing a bare-bones provisional yourself for just the government fee, then discovering 11 months later that it can’t support your actual invention.

At Rapacke Law Group, we approach this differently with our fixed-fee model. You know precisely what you’re investing upfront, no surprise hourly bills, no meter running while we research your technology. This transparent pricing lets you budget confidently and make strategic decisions without worrying about escalating legal costs.

The strategic calculus:

- Option 1: Spend $5,000 now on a thorough provisional that fully describes your invention. If you proceed, this will serve as the foundation for your non-provisional. If you don’t proceed, you’re out $5,000 but avoided a much larger commitment.

- Option 2: Spend $300 on a minimal provisional. You’ve saved money upfront, but if the invention proves valuable, you’ll likely need to file the non-provisional with a later effective date for claims not supported by the provisional, potentially losing priority to competitors who filed in the interim.

- Option 3: Skip the provisional and file a complete non-provisional immediately for $10,000–$15,000. Your application will be examined more quickly, and you’ve saved on filing the provisional.

Data shows that higher provisional usage in chemical/medical sectors correlates with patent term value concerns—in fields where patent term matters commercially (like pharmaceuticals with long development cycles), maximizing the patent term by using the full provisional year makes financial sense.

The 12-Month Countdown: Critical Deadlines You Cannot Miss

The 12-month deadline to file a non-provisional application is absolute and cannot be extended. Miss it, and your provisional becomes worthless. This is not like copyright or trademark deadlines that sometimes offer wiggle room—the USPTO is strictly bound by statute.

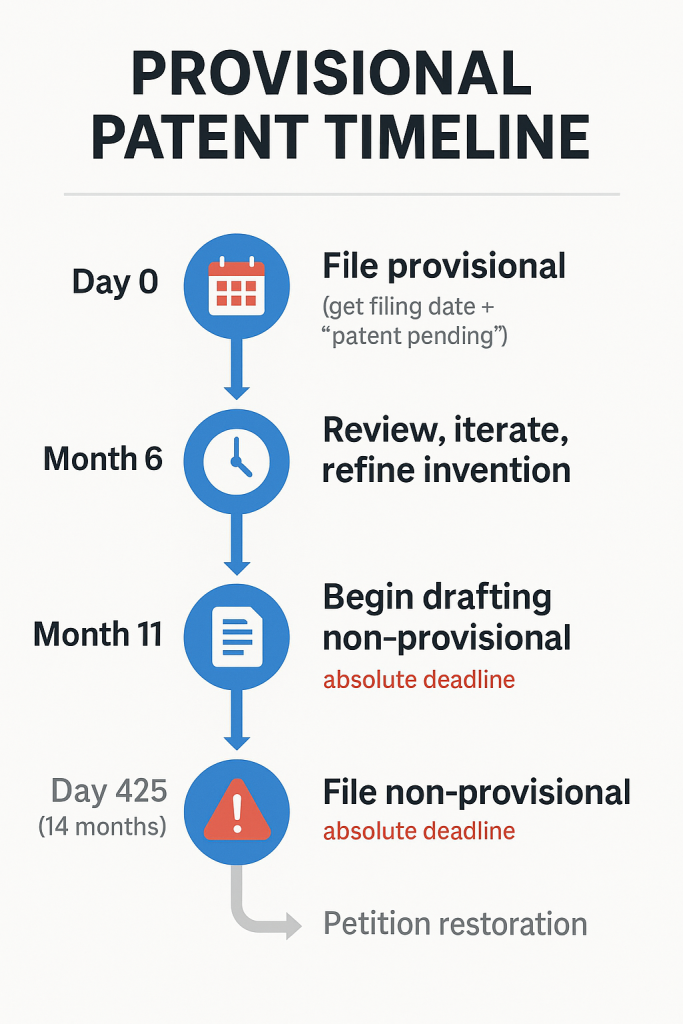

The critical date math:

- Day 0: Provisional filed (filing date established).

- Day 365 (12 months): Absolute deadline for filing a non-provisional claiming priority.

- Day 425 (14 months): Final deadline to petition for unintentional delay restoration.

Figure 1: The Provisional Patent Timeline illustrates the critical 12-month window inventors have between filing a provisional application and submitting a non-provisional patent. Each milestone —filing, refining, drafting, and final submission —is clearly mapped, with red alerts marking absolute deadlines and a gray grace period for restoration petitions—source: USPTO.

There is a narrow safety valve: if you file the non-provisional between 12 and 14 months, you can petition for restoration of priority by proving the delay was unintentional and paying a fee. But this is expensive, discretionary, and intended only for genuine emergencies, not a planning tool.

Real deadline management strategy: Most experienced patent attorneys aim to file the non-provisional by month 11, not month 12. This buffer accounts for:

- Unexpected delays in drafting or client review.

- Last-minute technical questions requiring inventor input.

- USPTO electronic filing system issues (yes, they happen).

- Business disruptions (illness, key employee departure, funding crises).

The provisional year sounds generous until you factor in year-end holidays, the time required actually to draft comprehensive claims and specifications, and the reality that most businesses move more slowly than anticipated.

What happens at 12 months if you don’t file: The provisional automatically becomes abandoned by operation of law. The USPTO won’t send reminders. The application simply expires. Suppose you had publicly disclosed your invention during the provisional period (relying on the pending status). In that case, you may have forfeited the ability to get a patent at all—that public disclosure becomes prior art against any later filing.

How to Prepare a Provisional That Actually Works

The single most significant mistake inventors make is treating the provisional as a rough sketch. The USPTO emphasizes that “the disclosure of the invention in the provisional application should be as complete as possible” to ensure adequate support for later claims.

For AI and software inventions, this means documenting not just what your code does, but how it achieves novel results. Describe your training data structures, algorithmic approaches, optimization techniques, and system architecture. Include pseudocode or flowcharts. The more technical detail you provide now, the broader your claim scope options later. For comprehensive guidance on protecting AI innovations, check out our AI Patent Mastery resource.

What “complete disclosure” actually means:

- Describe every component and variation you might claim. If your invention is a mechanical device, describe the materials, dimensions, connections, and operating principles. If it’s a software method, describe the algorithm, data structures, and implementation details. If it’s a chemical composition, explain the ingredients, their proportions, the synthesis methods, and the properties. If your invention involves a new material, be sure to describe its composition, properties, and methods of making it in detail.

- Include alternatives and embodiments. Don’t just describe the single version you’ve built. Describe variations: alternative materials, different configurations, and optional features. When you later draft claims, you’ll want flexibility to claim broadly. Each variation described in the provisional gives you claim options.

- Explain the problem and solution clearly. Patent examiners need to understand what makes your invention novel. Describe the prior art problem you’re solving and how your invention solves it differently or better. This context supports your claims during the examination.

- Provide examples and data. Concrete examples make your invention easier to understand and help establish enablement (that someone skilled in the art could make and use it). If you have test results, prototypes, or working models, document them in the provisional.

While formal patent drawings aren’t required for provisionals (you can include hand sketches, CAD drawings, or photographs), clarity is essential. Good figures can convey technical details more efficiently than text. Label components and reference them in the description.

Time investment for proper preparation:

Prior art research can take anywhere from two weeks to three months, depending on the complexity of your invention and existing art. Don’t skip this step—understanding what’s already out there helps you describe what’s actually new about your invention.

Detailed description drafting can take 2–6 weeks. This isn’t something to bang out in an afternoon—plan for multiple drafts, technical review by the inventor, and refinement to ensure completeness.

The preparation phase typically spans several weeks to a few months. Yes, this feels slow when you’re excited about your invention. But remember: a provisional filed with insufficient detail is worse than waiting an extra month to file it properly. The additional month of preparation time is negligible compared to the 12-month priority date you’re securing.

The Non-Provisional Transition: Where Most Mistakes Happen

When filing the non-provisional, you must identify the provisional application so the USPTO knows to accord the priority date. This is done in the Application Data Sheet (ADS) by listing the provisional application number and filing date.

The reference must be added within the latter of 4 months of filing or 16 months of the provisional date. While this sounds forgiving, it’s a better practice to include the priority claim at the time of filing rather than adding it later.

- Inventorship continuity. The non-provisional must have at least one inventor in common with the provisional to claim priority. If you added a co-inventor during the year who contributed to improvements, you can still claim priority as long as at least one inventor appears on both applications.

- Don’t “convert” the provisional. While there’s a procedure to convert a provisional into a non-provisional by petition, this is rarely recommended because it shortens your patent term by up to 12 months. Always file a fresh non-provisional that claims priority to the provisional rather than converting the provisional.

- Ensure claim support. The provisional’s description must support every claim element in the non-provisional to get the benefit of the provisional date. If you add new matter in the non-provisional that wasn’t disclosed in the provisional, those claims will have the later filing date.

Critical filing considerations: For founders and companies developing AI or machine learning solutions, understanding machine learning intellectual property protection is essential to maintain a competitive advantage and avoid unauthorized use

Example of a support problem: Your provisional describes a smartphone app with features A, B, and C. During the year, you develop feature D. You can certainly include feature D in the non-provisional specification and claims. But claims covering feature D will have the non-provisional filing date, not the provisional date. If a competitor filed something covering feature D during your provisional year, you can’t claim priority over them for those claims.

This is why thorough provisional disclosure matters so much; the more you describe initially, the more claim scope you can support with the early filing date.

Current USPTO Timelines: What to Actually Expect

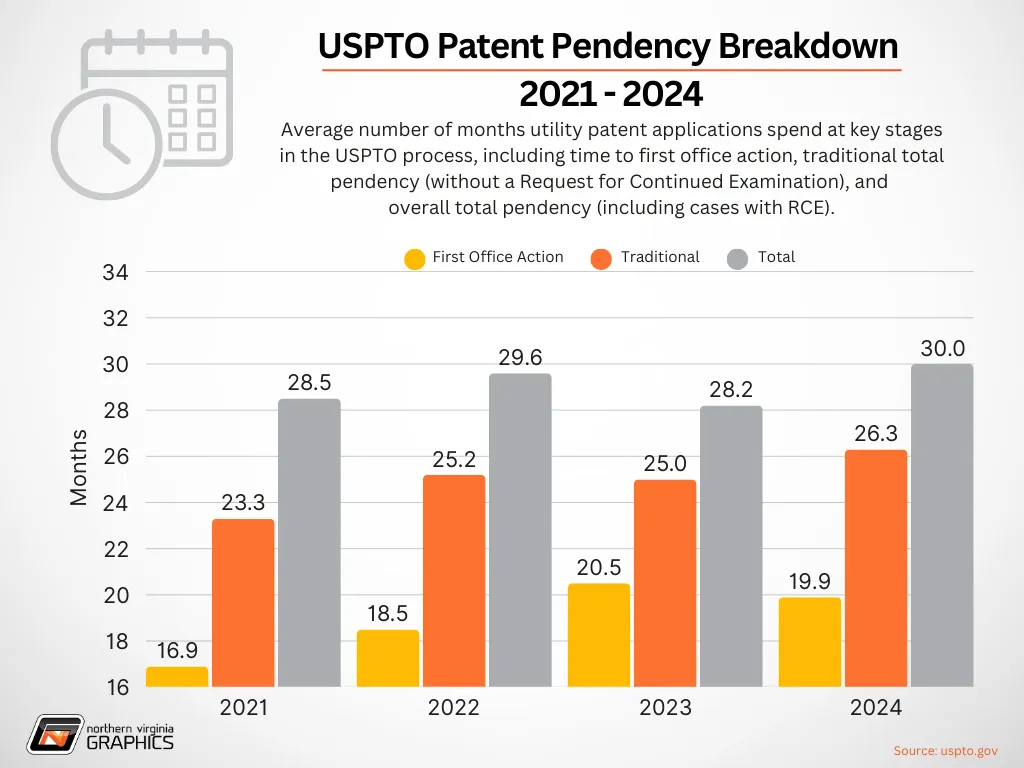

Patent pendency has been increasing. The average time to first Office Action increased from approximately 16.9 months in fiscal year 2021 to 20.5 months in 2023, then improved to 19.9 months in 2024. These statistics specifically refer to utility patent applications.

Total pendency from filing to final disposition averaged 26.3 months in 2024 for applications without a Request for Continued Examination (RCE), and approximately 30 months for applications that required an RCE.

What this means for your timeline:

From the day you file your provisional to receiving an issued patent, you’re typically looking at 3–4 years minimum:

- Year 1: Provisional pendency (12 months).

- Year 2: File non-provisional, wait for first Office Action (~20 months from non-provisional filing).

- Year 3: Respond to Office Action(s), examiner reviews response (~4–6 months per cycle).

- Year 4: Final disposition and issuance (if all goes well).

Certain technology areas, like software, have longer waits, often exceeding 20 months to first action, due to higher application volumes in those fields.

The USPTO’s backlog has grown to approximately 1.19 million pending applications by 2024, with unexamined applications up about 23.5% from 2021. This backlog directly impacts wait times.

The publication timeline: Non-provisional applications are typically published 18 months from the earliest priority date. If you filed a provisional, that means your non-provisional might publish just 6 months after you file it (since 18 months from the provisional date could be only half a year after the non-provisional filing).

Provisional applications themselves are not published or publicly accessible. They remain confidential unless you proceed to a non-provisional. This creates an interesting option: if you file a provisional, then decide not to pursue a patent, the invention stays secret. You could pivot to trade secret protection instead, and the abandoned provisional will never surface publicly.

Accelerated Examination: When You Need Speed

Sometimes waiting 3–4 years for a patent is untenable. You might need an issued patent to enforce against an infringer, to satisfy investor requirements, or to complete a business transaction. The USPTO offers expedited options.

Track One Prioritized Examination: This program guarantees final disposition within 12 months of filing the request, with a final decision (allowance or final rejection) issued within that timeframe. Many Track One applications receive a first Office Action within a few months and reach allowance in 6–12 months.

The cost is substantial—several thousand dollars in addition to standard fees—but the time savings can be worth it. The program has limits on the number of claims and requires that you are seeking a utility patent. Track One is only available for utility patents, not for design or plant patents.

When to use Track One:

- You need an issued patent to enforce against a known infringer.

- An investor or acquirer requires issued patent(s) as a deal condition.

- You’re in a race with competitors and need patent rights quickly.

- The commercial window for your product is narrow.

When not to bother:

- Your invention is still under development (no urgency for the patent).

- You’re using the “patent pending” period for market testing.

- The standard timeline aligns fine with your business plans.

You can file Track One when submitting your non-provisional or shortly after. The key requirement: you must respond quickly to any Office Actions to maintain the fast track. If you take the standard 3-month response time, you’ll defeat the purpose of expedited examination.

What Happens If You Do Nothing: Strategic Abandonment

If you don’t file any non-provisional by the 12-month deadline, the provisional application expires and is abandoned by operation of law. It’s as if it never existed for patent rights purposes.

Abandonment might be the right choice when:

- Market validation failed. You filed the provisional optimistically, but customer research during the year revealed insufficient market demand. Better to spend $300–$5,000 on a provisional and learn this than $50,000 on a full patent prosecution.

- The technology evolved. What you invented 12 months ago is already obsolete. Rather than patenting old technology, you’d prefer to file a new provisional (or non-provisional) covering the current version.

- Competitive landscape shifted. You discovered during the year that competitors have strong patent positions covering similar technology, making your patent’s value questionable.

- Trade secret is better. For some inventions, keeping them secret provides better protection than a published patent. If you can maintain secrecy and the invention isn’t reverse-engineerable, trade secret protection lasts indefinitely (versus 20 years for a patent).

The confidentiality advantage: Abandoned provisionals are not published. The content remains confidential with the USPTO. This means if you decide not to pursue the patent, competitors never learn what you disclosed in the provisional.

However, there’s a critical caveat: if you publicly disclose your invention during the provisional period and then abandon it without filing a non-provisional application, you may have forfeited all patent rights. That public disclosure becomes prior art that bars you from filing a patent later, and it doesn’t create prior art against others because your provisional was never published.

The International Dimension: PCT and Foreign Filing

The provisional’s filing date marks the start of the Paris Convention priority year for foreign filings. This means you have 12 months from the provisional date to file the corresponding international applications while still claiming the U.S. date.

Most inventors use the PCT (Patent Cooperation Treaty) system for international filing. You can file a single PCT application within 12 months of your provisional, designating multiple countries. This gives you an additional 18–30 months before you must enter the national phase in each country, effectively extending your decision timeline to 30–42 months from the original provisional.

Strategic timeline for international protection:

- Month 0: File U.S. provisional.

- Month 11: File PCT application and U.S. non-provisional (both claiming priority to provisional).

- Month 30: Enter national phase in selected countries (Europe, China, Japan, etc.).

This staged approach lets you defer expensive foreign filing decisions until you’ve had 2.5 years to assess commercial prospects and raise capital.

Research shows that approximately 15–18% of U.S. provisional applications are used to claim priority for European Patent Office filings, indicating that international strategy significantly influences provisional filing decisions, particularly for technologies with global markets.

The Bottom Line: How to Use Your 12 Months Wisely

The provisional patent’s real value isn’t the government filing fee saved—it’s the strategic optionality you purchase. For $300–$5,000 (depending on DIY versus professional preparation), you buy:

- A defensible filing date in the first-to-file system.

- Twelve months to develop the invention, test markets, and seek funding.

- “Patent pending” status that signals credibility to investors and deters some competitors.

- International filing flexibility via the Paris Convention priority year.

But you only capture this value if you:

- File a complete provisional that fully describes your invention (don’t cut corners on disclosure).

- Mark your calendar for the 12-month deadline and plan to file the non-provisional by month 11.

- Use the provisional period actively for R&D, market validation, and non-provisional preparation—not as a procrastination tool.

- Decide strategically whether to proceed based on commercial prospects, not the sunk-cost fallacy.

The provisional patent gives you up to 12 months of breathing room to refine the invention, explore its market potential, and prepare a strong non-provisional application. That breathing room becomes suffocating if you ignore the deadline or file an inadequate disclosure.

The 149,000 inventors who filed provisionals in 2023 weren’t all successful. Roughly half never converted to full applications. But the ones who succeeded shared a common approach: they treated the provisional as a serious legal document deserving proper preparation, and they used the 12-month window strategically rather than passively.

Your provisional patent timeline starts the moment you file. What you do with those 12 months determines whether the $300 becomes your smartest IP investment or a wasted fee.

Your Next Steps to Provisional Patent Success

You now understand the provisional patent timeline, from the critical 12-month deadline to the strategic disclosure requirements that determine whether your filing actually protects your priority date. But understanding the process and executing it flawlessly are two different things.

The bottom line: A weak provisional application doesn’t just fail to protect your invention, it actively helps your competitors. While you’re operating under the false security of “patent pending” status, a competitor who filed a complete disclosure gains the priority date that should have been yours. By the time you discover the problem 11 months later, they’ve already locked you out of the key claim scope.

Here’s what’s at stake: Miss the 12-month conversion deadline, and you lose everything—your priority date evaporates, your provisional becomes worthless, and any public disclosures you made during that year now count as prior art against you. In the first-to-file system, that timing gap can mean the difference between owning your market and watching competitors patent the technology you developed first. For SaaS founders and tech startups, this translates directly to lost valuation, failed funding rounds, and diminished exit opportunities.

The RLG Guarantee for Provisional Patents:

When you work with Rapacke Law Group on your provisional patent application, you get:

- FREE strategy call with our experienced patent team to evaluate your invention and disclosure strategy.

- Experienced US patent attorneys lead your application start to finish, not paralegals or supporting staff.

- One transparent flat-fee covering your entire provisional patent application process (no surprise hourly bills or hidden charges).

- Full refund if USPTO denies your provisional patent application*.

- Full refund or additional searches if your application has patentability issues (your choice)*.

We’re so confident in our provisional patent process that we guarantee results or return your investment.

Take these immediate actions:

- Schedule a Free IP Strategy Call to evaluate your invention’s patentability, identify the critical technical details that must be in your provisional, and develop a strategic timeline that maximizes your 12-month window while meeting your business goals.

- Document your invention thoroughly before any public disclosure. Start compiling technical specifications, flowcharts, test results, and alternative embodiments now—this preparation accelerates the drafting process and ensures nothing critical gets overlooked.

- Review your commercialization timeline to determine optimal filing and conversion dates. If you’re raising capital, consider how “patent pending” status affects your valuation and what investors need to see before committing.

- Assess international protection needs early. If you’ll need foreign patents, your provisional filing strategy should account for PCT timing and foreign filing costs from day one.

The provisional patent application is your first critical decision point in building defensible IP. Done right, it establishes an unassailable priority date while giving you strategic flexibility to refine your technology and business model. Done wrong, it’s a wasted filing fee that creates false security while competitors lock up the IP position you need.

Strong provisional applications set the foundation for robust patent portfolios that deter competitors and attract investors. At Rapacke Law Group, we specialize in helping tech startups and inventors file provisional applications that actually work—complete disclosures that support broad claim scope, fixed-fee pricing that eliminates billing surprises, and strategic guidance that aligns your IP timeline with your business objectives.

Don’t let incomplete disclosure or missed deadlines cost you your competitive advantage. The 12-month clock starts the moment you file. Make sure every day of that year builds toward a strong non-provisional application and enforceable patent rights.

About the Author:

Andrew Rapacke is Managing Partner and a Registered Patent Attorney at Rapacke Law Group, where he specializes in patent strategy for tech startups, SaaS companies, and AI innovators. Connect with Andrew on LinkedIn or follow @rapackelaw for insights on patent strategy and IP protection.

To Your Success,

Andrew Rapacke

Managing Partner, Registered Patent Attorney

Rapacke Law Group

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the main difference between a provisional and a non-provisional patent application?

The main difference is that a provisional patent application does not require formal claims or examination, and it primarily serves to establish an early filing date. In contrast, a non-provisional application must include claims and undergo examination. A provisional application never by itself turns into an issued patent—it’s a placeholder that expires after 12 months, while a non-provisional is the actual patent application that can mature into an enforceable property right.

How long does it take to prepare a provisional patent application?

It typically takes from a few weeks to several months to prepare a provisional patent application, depending on the invention’s complexity and the depth of the research and drafting involved. Prior art research can take two weeks to three months, while detailed description drafting can take 2–6 weeks. The investment in time is worth it to ensure your provisional fully supports your future patent claims.

What happens if I miss the deadline to file a non-provisional application?

Missing the 12-month deadline means you lose the benefit of your provisional application’s filing date. The provisional will expire and cannot be used to claim priority. There is a limited remedy: if you file a non-provisional a little late (within 14 months from the provisional), you can file a petition to restore priority, claiming that the delay beyond 12 months was unintentional. However, if you go beyond 14 months, even that safety net is gone.

Are there any maintenance fees for provisional patent applications?

No. Provisional patent applications do not have maintenance fees. Once you’ve filed the provisional and paid the filing fee, there are no further fees due to the USPTO for that application during its 1-year life. This lack of ongoing fees is one reason provisionals are attractive for inventors. You can hold off on incurring more costs until you decide to file the full application.

Can I publicly disclose my invention during the provisional application period?

You can, but you should be very cautious. In the U.S., you have a 12-month grace period for your own disclosures, meaning if you disclose the invention after filing the provisional, you can still file the non-provisional within 12 months without being barred by your disclosure. However, if you fail to follow up with the non-provisional in time, that public disclosure becomes prior art that can prevent you from getting a patent later. Most countries require absolute novelty—public disclosure before filing destroys patentability abroad. The safest route is to keep your invention confidential until you file the non-provisional. For a step-by-step guide on how to patent software, refer to this resource.