Most inventors lose their patent rights before they ever apply, and they don’t even realize it. A single tweet, one Product Hunt launch, or a demo day presentation can permanently destroy your ability to patent an invention worth millions. At Rapacke Law Group, we work exclusively with SaaS founders and tech innovators to navigate these pitfalls through transparent, fixed-fee patent services. Unlike traditional $500-800/hour BigLaw firms, we understand that your runway is precious and your budget needs predictability.

In 2023 alone, the USPTO received over 418,000 patent applications but granted only 312,000 patents, meaning roughly 25% failed to clear the patentability hurdles. Understanding which conditions your invention must satisfy isn’t just academic; it’s the difference between securing a 20-year monopoly and watching competitors freely copy your breakthrough, especially critical for software and AI innovators, where the patentability landscape has shifted dramatically since the Alice decision.

Why This “Which Are the Conditions of Patentability“ Guide Matters for Tech Founders

If you’re like most SaaS founders we work with, you’ve probably encountered one of these frustrating scenarios:

The BigLaw Problem: You contacted a traditional patent firm and received a quote for $25,000-35,000 for patent preparation, with vague timelines and hourly billing at $500-800/hour. When you asked for a fixed quote, they couldn’t provide one because “every case is different.” You can’t get board approval for an open-ended expense, and you’re not even sure if your invention is patentable.

The Generalist Problem: You worked with a general IP attorney who handles trademarks, contracts, and occasionally patents. When the USPTO issued an Alice rejection on your software patent, they seemed uncertain how to respond. You realized too late that software patent eligibility requires specialized expertise, not general IP knowledge.

The DIY Problem: You considered using an online patent service to save money, but quickly realized that filling out forms isn’t the same as building a defensible patent strategy. Without claim drafting expertise, you’d likely end up with a granted patent that’s too narrow to block competitors or too broad to withstand validity challenges.

The Rapacke Law Group Difference: We built our practice specifically to solve these problems for tech innovators. Every attorney on our team specializes in patents and trademarks for software, AI, and SaaS companies, not dabbling in patents alongside corporate law or litigation. We offer completely transparent, fixed-fee pricing with no hourly billing surprises, so you know precisely what patent protection will cost before we start. And we back our patentability searches with a guarantee that no other firm provides.

This is especially critical for software and AI innovators, where the patentability landscape has shifted dramatically in recent years. If you’re building a SaaS platform, developing machine learning algorithms, or creating AI-powered tools, understanding these requirements and working with attorneys who specialize in software patent strategy can mean the difference between a defensible competitive moat and an expensive application that goes nowhere.

This guide breaks down the exact legal requirements patent offices worldwide use to separate genuine innovations from ideas that don’t qualify for protection. These aren’t arbitrary standards; they’re grounded in statutes, treaties, and decades of case law designed to balance inventors’ rights with the public interest. Keep in mind that patent law is largely harmonized globally. International agreements like TRIPS (Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights) obligate nearly all countries to follow the same basic criteria: inventions must be new, involve an inventive step, and be capable of industrial application.

Which Are the Conditions of Patentability? Quick Answer: The Four Core Conditions of Patentability

Every modern patent law imposes four classic patentability criteria. If you remember nothing else, remember these four hurdles that an invention must clear to be patentable:

- Patentable subject matter: The invention must fall within the statutory categories of process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter (as defined in Section 101 of the Patent Act) and avoid excluded categories like abstract ideas or purely natural phenomena.

- Novelty: The invention must be new. It cannot have been publicly disclosed anywhere in the world before the relevant filing date.

- Inventive step / Non-obviousness: The invention must represent more than a trivial or obvious modification over what was already known. It needs to be a non-obvious advance to a person having ordinary skill in the art.

- Industrial applicability / Utility: The invention must actually work and have a specific, real-world use (it can’t be just a theory or a useless concept).

Meeting all four conditions is necessary for patentability. If any of these criteria is not met, the patent will not be granted (or, if granted, may be invalidated later). In fact, statistics from U.S. patent examination show that rejections for lack of novelty (§102) or obviousness (§103) are very common: together with clarity issues, they account for over 70% of all examiner rejections. Only genuine innovations that clear each hurdle earn the 20-year monopoly that a patent confers.

Did you know? The global adoption of these criteria was cemented by the TRIPS Agreement in 1994, which requires WTO member countries to grant patents for inventions that are new, involve an inventive step, and are capable of industrial application (with “inventive step” and “industrial application” being deemed synonymous with non-obviousness and utility in U.S. parlance). This international baseline helps ensure inventors face similar hurdles in all significant markets.

Legal Framework: Where Do the Conditions of Patentability Come From?

The conditions of patentability aren’t arbitrary; they’re codified in national statutes and reinforced by international treaties that harmonize patent requirements across borders. Understanding the legal basis can help you see why these rules exist and how they’re interpreted.

In the U.S., patent law (35 U.S.C. § 101) also specifies that the subject matter must be “useful,” and enablement is a fifth key requirement under U.S. law (i.e., the patent application must describe the invention in sufficient detail that a person skilled in the art can make and use it). In the U.S., the five key criteria are: patentable subject matter, utility, novelty, non-obviousness, and enablement.

These core requirements appear in virtually every jurisdiction’s patent laws, from the United States (35 U.S.C. §§ 101–103) to Europe (Articles 52–57 of the European Patent Convention), to patent systems across Asia and beyond. The numbering and terminology differ (e.g., the U.S. uses “utility” while Europe uses “industrial applicability”), but the substantive inquiry is remarkably consistent.

United States: The Patent Act

The Patent Act (Title 35, U.S. Code) sets out the core requirements:

- 35 U.S.C. § 101 defines patentable subject matter and the utility requirement, covering “any new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof.”

- 35 U.S.C. § 102 establishes the novelty requirement and defines what counts as prior art (all the public information that predates your filing).

- 35 U.S.C. § 103 governs non-obviousness (inventive step).

- 35 U.S.C. § 112 (not listed above but critically important) requires a clear and enabling disclosure.

The America Invents Act (AIA) of 2011 overhauled U.S. patent law and transitioned the U.S. to a first-inventor-to-file system (effective March 16, 2013), aligning it more closely with Europe and other countries. This means that in the U.S. today, patent rights generally go to the first inventor to apply, not the first to invent. For SaaS founders and tech startups racing to establish a market position, filing speed and strategic timing are absolutely critical; hesitation can mean losing your patent rights to a competitor who files first.

Europe: The European Patent Convention

The European Patent Convention (EPC) defines patentable inventions in Articles 52–57:

- Article 52 EPC mirrors the broad categories of patentable subject matter (inventions that are industrially applicable, new, and involve an inventive step), while explicitly excluding things like discoveries, scientific theories, mathematical methods, aesthetic creations, schemes or rules for doing business, and presentations of information “as such”

- Articles 54–56 EPC cover novelty (54), inventive step (56), and also mention the state of the art for prior art

- Article 57 EPC addresses industrial applicability (utility)

- Additionally, Article 83 requires a sufficient disclosure of the invention

Additionally, national laws in EPC member states generally align with the EPC in terms of substantive conditions.

International Treaties

The TRIPS Agreement (1994), Article 27, requires that patents be available for inventions in all fields of technology, provided they are new, involve an inventive step, and are capable of industrial application. TRIPS allows members to interpret “inventive step” and “industrial application” as synonymous with non-obviousness and utility. Practically speaking, this treaty harmonized the three main requirements (novelty, inventive step, utility) among all WTO members.

The Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) provides a process for international patent applications. While the PCT doesn’t itself grant patents, it includes a global search and preliminary examination for novelty, inventive step, and industrial applicability. The substantive examination is ultimately conducted in each chosen country/region during the national phase, in accordance with its laws (which, under TRIPS, share common criteria).

In short, the four conditions of patentability are embedded in law. Court decisions further refine these standards. For example, U.S. Supreme Court rulings like KSR v. Teleflex (2007) clarified the non-obviousness test, and Mayo (2012) and Alice (2014) explained the bounds of abstract ideas and natural laws under §101. Similarly, in Europe, decisions of the EPO’s Boards of Appeal (and national courts) continuously shape how these requirements apply in emerging fields.

Patentable Subject Matter: What Kinds of Inventions Qualify?

Not every idea is eligible for a patent, no matter how novel or non-obvious it might be. Patent laws first ask “Is this the kind of thing we even patent?” before delving into novelty or inventive merit. This is the subject matter eligibility inquiry. Each jurisdiction defines what categories of inventions are patent-eligible and which are excluded on policy grounds.

This is where many SaaS founders and AI innovators hit their first roadblock. The line between an unpatentable ‘abstract idea’ and a patentable ‘technical innovation’ can feel frustratingly arbitrary, but understanding the nuances can save you months of wasted effort. For comprehensive guidance on navigating these challenges, see our AI Patent Mastery guide.

Under U.S. law, 35 U.S.C. § 101 defines patent-eligible subject matter extremely broadly as “any new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof.” This wide net can cover everything from chemical compounds to manufacturing methods to electronic devices and software-implemented processes. However, the U.S. Supreme Court has carved out judicial exceptions: concepts that are not patentable even if they fit those broad categories, because allowing patents on them would hinder, not promote, innovation. The three key exclusions are:

- Abstract ideas: e.g., pure mathematical formulas or fundamental economic practices. (If your claim boils down to a disembodied idea or algorithm without a practical application, it’s likely considered abstract.)

- Laws of nature: e.g., natural relationships or scientific truths like E = mc², or the correlation between a biomarker and a disease.

- Natural phenomena (products of nature): e.g., a naturally occurring gene or pure natural substance discovered in the wild.

These exclusions reflect the principle that no one should monopolize “the basic tools of scientific and technological work.” In practice, many borderline inventions (especially in software, business methods, and biotech) live in a gray area between an unpatentable abstract idea/natural law and a patentable application of that idea/law. U.S. examiners apply the Alice/Mayo test (from Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank (2014) and Mayo v. Prometheus (2012)) to such cases: first determining if the claim is directed to a judicial exception, and if so, then checking if it contains an “inventive concept” that transforms it into a patent-eligible application.

Concrete Examples of What Cannot Be Patented

What typically cannot be patented in the U.S.:

- A pure mathematical formula in isolation (e.g., an equation for calculating prime numbers): that’s an abstract idea.

- A method of organizing human activity or fundamental business practice done in the abstract (e.g., a process for hedging risk in trading, as in the Bilski case).

- Scientific theories or natural phenomena themselves (you can’t patent gravity or the fact that blood oxygen correlates to X, although you might patent a device or method applying that discovery).

- A naturally occurring substance or gene as it exists in nature. For instance, the Supreme Court’s Myriad Genetics decision (2013) held that isolating a naturally occurring human gene (BRCA1) was not patentable subject matter. In contrast, a synthetic DNA (cDNA) sequence, which is not naturally occurring, is potentially patentable because it results from human intervention.

What can often be patented with proper claim drafting:

- A specific data-processing method implemented on a machine that improves computer functionality (for example, a cybersecurity algorithm that significantly reduces network latency or a machine learning technique that achieves a concrete technical improvement). The key is that it’s tied to a technical solution, not just an abstract result.

- A new chemical or biotech product that humans created (even if inspired by nature). E.g., a non-naturally occurring recombinant DNA or a modified protein with new properties

- A software application that, for instance, improves the operation of a device or processes data in a novel way to achieve a tangible result (e.g., image processing yielding more accurate diagnostics). Many software inventions are patentable if claimed from the angle of technical innovation (and if they meet the other criteria)

Software and AI Patents: The Real-World Challenge

For SaaS founders and AI developers, this is where theory meets reality. Your natural language processing algorithm, your recommendation engine, or your data analytics platform might feel incredibly innovative. Still, the USPTO may see it as an “abstract idea” unless you frame it correctly.

The key is demonstrating how your software solves a technical problem technically. For example:

- Won’t pass: “A method for matching job seekers with employers using AI.”

- Might pass: “A system that reduces server load by 40% through distributed machine learning preprocessing, enabling real-time job matching at scale.”

The difference? The second emphasizes the technical challenge (server load and scalability) and the technical solution (a distributed preprocessing architecture), not just the business outcome.

At Rapacke Law Group, we’ve developed proprietary strategies for framing software and AI inventions to emphasize technical solutions rather than abstract business outcomes. Our fixed-fee approach means you know precisely what strategic patent preparation costs upfront, with no hourly billing surprises.

For a deeper dive into software and AI patent strategies, including specific claim drafting techniques that have successfully overcome §101 rejections, check out our AI Patent Mastery guide and SaaS Patent Guide 2.0.

The European Approach: Technical Character

In Europe, Article 52 EPC similarly excludes “discoveries, scientific theories, mathematical methods, aesthetic creations, schemes, rules and methods for performing mental acts, playing games or doing business, and programs for computers as such”. The crucial phrase “as such” means that these things are not patentable when claimed purely in that abstract form. However, Europe will allow patents on, say, computer-implemented inventions or business-oriented processes if they provide a novel technical solution. The European Patent Office (EPO) looks for a technical character or technical contribution. For example, a straightforward banking app that calculates interest likely fails (it’s just a business scheme). Still, a fintech software that solves a technical problem in network security or database efficiency could qualify because it has technical merit beyond the business idea.

Patent attorneys often devote considerable effort to drafting claims to emphasize the invention’s technical effects and practical applications, thereby ensuring it clears the subject-matter hurdle. This might involve framing a software invention in terms of improved computer functionality (memory management, speed, security, etc.) rather than simply as an “idea” for doing business.

Judicial and Statutory Exclusions to Patentability

Even if an invention is technically oriented, it may still be excluded from patentability for policy reasons. These exclusions vary by jurisdiction and are often explicitly codified:

Medical methods: Many jurisdictions exclude diagnostic, surgical, or therapeutic methods applied to the human (or animal) body. In Europe, EPC Article 53(c) bars patents on methods of treatment or diagnosis practiced on the body (the idea being that doctors and veterinarians should not be impeded by patents when saving lives). The U.S. doesn’t categorically exclude these methods in its statute, but it offers a defense for medical practitioners against infringement of medical procedure patents.

Plant and animal varieties; essentially biological processes: EPC Article 53(b) excludes patents on plant or animal varieties and on biological processes for producing them (like cross-breeding methods). The U.S. addresses plant innovation via separate pathways: e.g., Plant Patents for asexually reproduced plants, and allows utility patents on genetically engineered organisms, but not on a distinct plant variety that could be protected under the Plant Patent Act or plant breeders’ rights.

Inventions contrary to public order or morality: This clause appears in many laws (including EPC Art. 53(a)) and allows the refusal of patents for inventions that are illicit or immoral. It’s rarely invoked, but it has come up in contexts like human cloning processes or unduly cruel animal testing methods.

“Software as such” and “business methods as such” in Europe: As noted, the exclusion concerns the “as such.” Europe has developed extensive case law (e.g., EPO decisions such as COMVIK and Hitachi) to determine when a software or business-method claim has a technical character. If you draft it right (focusing on a technical problem and solution), you can often avoid the “as such” trap.

Abstract ideas in the U.S.: Post-Alice, the USPTO saw a surge in §101 rejections for software and business-method applications. By one account, after the Supreme Court’s Alice decision, the likelihood of receiving a §101 rejection in affected tech areas spiked dramatically, creating significant uncertainty. The USPTO issued revised guidance in 2019 that clarified the analysis, and indeed, the incidence of first-office-action §101 rejections dropped by 25% in the year after the guidance. However, patent eligibility in the U.S. remains a hot topic: as of 2025, Congress has considered legislation to reform §101.

It’s important to note that these exclusions are frequently litigated and evolve. For instance, what’s considered patentable subject matter in the realm of artificial intelligence or medical diagnostics has shifted over the past decade. U.S. courts and the USPTO have struggled with AI-related inventions: Is a purely AI-generated invention patentable? (As of now, the inventor must be human, per USPTO and EPO policy.) In medical diagnostics, the Mayo case (2012) made it harder to patent diagnostic correlations (viewed as natural law). Still, applicants now draft claims that emphasize laboratory techniques or specific applications to meet eligibility requirements.

Trend Alert: There is ongoing debate and reform efforts around patent eligibility. In the U.S., dissatisfaction with the unpredictable Alice/Mayo framework led to bipartisan bills, such as the Patent Eligibility Restoration Act of 2023. That proposal aims to roll back some judicial exclusions and define eligible subject matter more clearly (for example, ensuring that medical diagnostics and specific biotech innovations are patent-eligible, which courts have sometimes invalidated under the current rules). As of 2025, this legislation has not been enacted, but it highlights a push to “restore clarity” in this area. Similarly, all 12 judges of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit have at some point expressed frustration with the state of §101 law, indicating that change may eventually come either from Congress or from the Supreme Court revisiting the doctrine.

In summary, before worrying about whether your invention is new or non-obvious, make sure it passes this threshold test: Is it the type of thing the patent system is designed to protect? If you’ve invented a new practical device, system, or material, you’re likely fine. If it’s more of a discovery, an idea, or a scheme, you may need to work with a patent attorney to frame it appropriately, or accept that it falls in an excluded category.

Novelty: The Invention Must Be New

Novelty is the most intuitive patentability condition: your invention must be new, meaning it was not publicly disclosed before you filed your patent application. If all features of your claimed invention are found in a single patent or prior art reference (often called a ‘single patent’ anticipation), your invention is not considered novel. If someone else already described or used the same invention publicly, you generally cannot get a valid patent on it. The patent system is meant to reward genuine innovations, not allow latecomers to claim what’s already known.

For founders presenting at demo days, posting on Product Hunt, or showcasing at tech conferences, this requirement demands your immediate attention. One careless tweet about your ‘revolutionary new algorithm’ can torpedo your patent rights in most of the world. The solution? If we file a provisional patent application before any public disclosure, we can prepare and file a provisional in days, not weeks, when timing is critical.

What Counts as “Public Disclosure” or Prior Art?

Anything available to the public before your effective filing date (or priority date) can constitute prior art. This includes:

- Published patents and patent applications (worldwide).

- Articles in scientific journals, conference papers, and technical whitepapers.

- Books, websites, blogs, and other online content.

- Public demonstrations or use of the product (e.g., showcasing it at a trade show)

- Sales or offers to sell the product.

- YouTube videos, social media posts: yes, even a video or tweet can be prior art if it enables someone to recreate the invention.

A single enabling disclosure is enough to ruin novelty. For example, if an obscure blog post in 2022 (anywhere in the world, any language) described your invention in enough detail, and you file in 2024, that blog post is prior art that can anticipate (invalidate) your claim. Novelty is an absolute, binary test: either a single reference shows every feature of your claim (thus anticipating it), or not. If yes, your claim is not new.

Global Perspective on Novelty

Most countries operate under an absolute novelty standard: any public disclosure before filing is a bar to patentability. Europe, China, and many others have no general grace period: even your own disclosure can count against you if it was before filing.

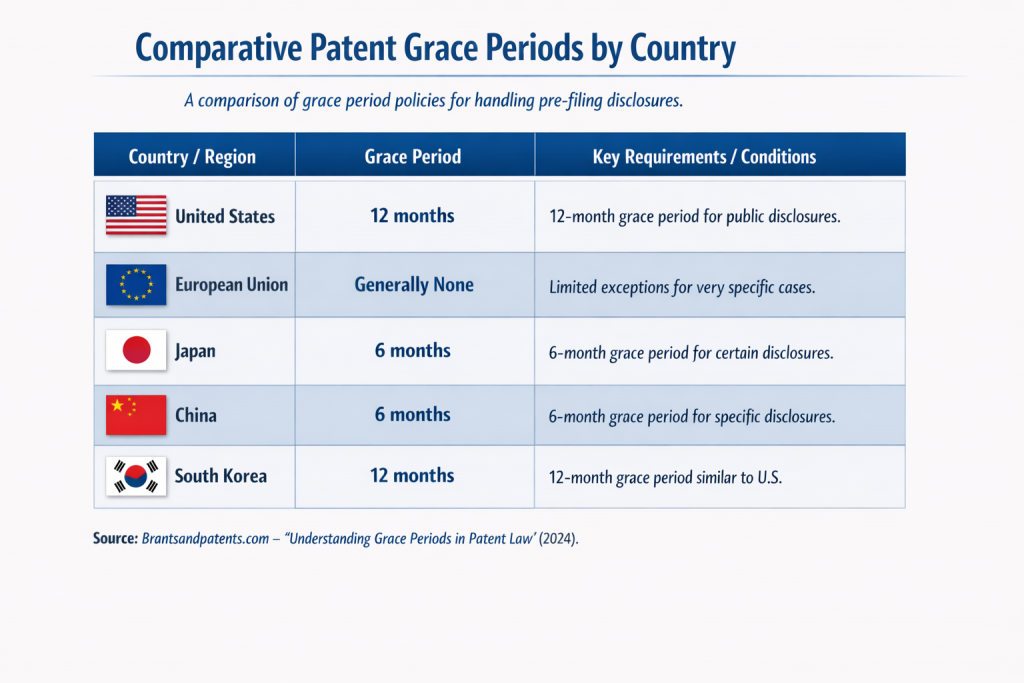

Figure 1: Patent grace periods vary widely by jurisdiction. While the United States and South Korea allow a 12-month grace period after public disclosure, Europe applies strict absolute novelty, and Japan and China provide only limited 6-month exceptions. Relying on a grace period can permanently bar patent rights outside the U.S.

U.S. Grace Period

If you (or your team/inventor) publicly disclose the invention, you have up to 12 months from that disclosure to file a U.S. patent application, and your own disclosure won’t count as prior art against you. This is a safety net unique to U.S. law. For example, if you gave a talk at a university on your invention in October 2024, you could still file a U.S. application by October 2025. However, be cautious: this grace period only shields your own disclosures (and those ‘obtained’ from you), not independent disclosures by others. And critically, outside the U.S., public disclosure would likely permanently destroy your patent rights: Europe, Japan, and most other countries don’t excuse public disclosures. The safest global strategy: file first, publish second.

Europe and Others: Absolute Novelty

Europe requires absolute novelty. There is no 12-month grace period for your own publication (except for a few narrow cases, such as disclosures at officially recognized exhibitions or disclosures due to abuse, which allow a 6-month window). In practice, this means that if you plan to file in Europe, do not publicly disclose the invention before filing. Japan and China offer a 6-month grace period in limited cases (often for an inventor’s disclosure), but these come with specific rules (e.g., you usually must declare the disclosure when filing). The safest strategy globally is to file first, then publish.

Prior Art Searches and Examination

When you file a patent application, the patent office will perform a prior art search to check novelty (and inventive step). For instance, U.S. examiners search the USPTO databases, international (PCT) publications, technical literature, and even internet sources for anything that matches your claims. The patent examiner will compare each claim of your application against prior art references. If they find a single reference that contains all elements of a claim, they will reject that claim for lack of novelty (often called an “anticipation” rejection under §102).

Insight: The vast majority of patent applications initially receive some form of prior art rejection. Novelty rejections are common, though they can often be overcome by amending the claims to include more detail or by arguing that the reference lacks a key element. An analysis of USPTO data (2014–2018) found that §102 (novelty) and §103 (obviousness) rejections together were by far the most prevalent, together comprising over 60% of all rejections. This underscores that patent examiners are rigorous in their review of the literature; you need to have something genuinely new and non-trivial.

First-Inventor-to-File vs. First-to-Invent

It’s worth noting that since the AIA, the U.S. has switched to a system in which, in patent contests, the filing date, not the date of invention, counts. In the pre-2013 era, if two inventors came up with the same idea, the one who could prove an earlier date of invention might win (a “first-to-invent” system), but that’s essentially history now. Today, if two people independently invent the same thing, the one who files a patent application first will get the patent (assuming all else is equal). There is a limited exception for derivation (if someone stole the idea from the true inventor), but generally it’s a race to the Patent Office. So being prompt in filing can be critical.

Public Disclosure Pitfalls and the On-Sale Bar

Timing matters enormously. Some key practical points:

In the U.S., there’s a concept of a “statutory bar” for certain events more than 1 year before filing:

- If your invention was on sale more than one year before your U.S. filing date (even if the sale was not public, under the current interpretation), you are barred from patenting it. For example, if you started selling a gadget in January 2024 and only in March 2025 tried to file a patent, it’s too late: the sale (even a secret sale) in Jan 2024 would bar the patent.

- If your invention was in public use (with no secrecy obligation) more than one year before filing, likewise, you’re barred.

- The AIA slightly tweaked these bars, but fundamentally, they prevent people from commercially exploiting an invention for a long time and then later seeking a patent.

In Europe and elsewhere, any public use or sale before filing is disqualifying (no one-year grace at all). Many startups have been dismayed to learn that their public crowdfunding campaign or product launch, conducted before filing, has cost them foreign patent rights. For instance, demonstrating your prototype at CES or listing it on Kickstarter before securing a filing date can be fatal to patent prospects outside the U.S.

Best Practices to Preserve Novelty

File early: Ideally, file a provisional patent application before any public disclosure (pitch, presentation, launch, publication). A provisional is relatively low-cost and establishes a filing date.

Use NDAs for non-public discussions: If you need to discuss your invention with manufacturers, investors, or partners, have them sign a Non-Disclosure Agreement. A disclosure under NDA is generally not “public,” so it won’t count as prior art. (Be careful, though: in some countries, any disclosure outside the patent office can be risky. But NDAs are a good standard practice.)

Beware of third-party disclosures: Even if you stay quiet, someone else might publish something similar. Keep an eye on your field. If you see others getting close, that’s a signal to file quickly. Also, if you’ve disclosed under NDA to a company, and they leak it or file their own application, it can complicate things, so choose trusted partners.

Consider foreign filing strategies: If you do accidentally disclose publicly, the U.S. grace period might save you domestically, but you may have zero protection in Europe and Asia unless you file within days of disclosure. In some industries, losing foreign patent rights might be acceptable; in others, it’s a significant loss. At Rapacke Law Group, we help you strategize international filing under the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) to maximize global protection while managing costs strategically. If novelty is compromised but the invention isn’t easily reverse-engineered, we can also advise on pivoting to trade secret protection.

Key point: If your invention has been publicly disclosed before you filed, you’re generally too late to patent it in most of the world. And if someone else independently invented and published it first, you cannot get a patent on it either. Do your homework with prior art searches and act swiftly to secure a filing date. The patent system rewards the vigilant and the first to file.

Inventive Step / Non-Obviousness: More Than a Trivial Change

So your invention is new: no one has done it before. That’s great, but it’s not enough. The next filter is inventive step (as it’s called outside the U.S.) or non-obviousness (the U.S. term). This criterion asks: Would the invention have been evident to a skilled person in light of the prior art? If the answer is yes (even if no single reference shows it, it was an obvious next step), then a patent should not be granted.

In everyday terms, the patent office doesn’t want to give monopolies for “garden-variety improvements” that any competent person in the field could deduce. The invention has to reflect some ingenuity that wasn’t readily apparent.

The U.S. Standard

Under 35 U.S.C. § 103 (U.S.), an invention is not patentable “if the differences between the claimed invention and the prior art are such that the claimed invention as a whole would have been obvious to a person having ordinary skill in the art at the time of the invention.” All those words are essential:

- “differences… are such that it would have been obvious”: This means examiners can combine multiple prior art references to piece together your invention. Maybe no single earlier patent had all your features, but Patent A had most of them, and Patent B suggested the rest; if so, the examiner might argue it’s obvious to combine A and B.

- “as a whole”: You look at the invention as a complete package, not just individual differences in isolation.

- “person having ordinary skill in the art” (often abbreviated PHOSA or PHOSITA): This hypothetical person is central to the test. They are not the Einstein or Nobel laureate of the field, but they are not a newbie either. They have normal skills and knowledge of a typical practitioner in that technical area. Obviousness is judged from their viewpoint at the time of filing (or time of invention, pre-AIA). If this skilled person had considered the invention obvious, there would be no patent.

Examiner Tactics: Combining References

Patent examiners almost always handle obviousness by citing multiple prior art references. For example: “Reference A teaches a widget with elements X, Y, Z. Reference B teaches adding element W to similar widgets to improve efficiency. Therefore, claim 1 (which has X, Y, Z, W) is rejected as obvious in view of A + B.” The idea is that someone skilled in the art would naturally combine A and B to get your invention.

Since 2007, examiners have had greater flexibility due to the Supreme Court’s decision in KSR v. Teleflex. Before KSR, they often had to identify a specific “teaching, suggestion, or motivation” (TSM) in the prior art to combine references. KSR said, ” Don’t be so rigid: common sense and general knowledge can suffice. The Court noted that “a combination of familiar elements according to known methods is likely to be obvious when it does no more than yield predictable results.” In practice, if your invention is just combining two known elements and nothing unexpected happens, it’s likely obvious (making it essential to consider a Freedom to Operate strategy before pursuing commercialization). Examiners can argue that even if prior art documents don’t explicitly suggest the combination, if the field of technology trends that way, or it’s a logical improvement, that’s enough.

The European Approach: Problem/Solution

The European Patent Office uses a very structured method:

- Identify the “closest prior art”: the single reference most similar to your invention

- Determine the “objective technical problem” that your invention is solving, in view of the prior art

- Ask: Given that problem, would the solution (your claimed invention) have been obvious to the skilled person? If yes, no patent; if no (i.e., it wasn’t obvious to solve that problem in that way), then it involves an inventive step

This approach tries to minimize hindsight bias. It’s essentially a more formulaic way to assess obviousness, aiming to ensure the examiner doesn’t use your invention as a roadmap to cherry-pick pieces of prior art unless it’s truly logical to do so.

The Prevalence of Obviousness Rejections

Obviousness is where most patent applications struggle. In fact, statistics bear this out: Historically, obviousness (§103) is the single most common ground for rejection. One study of USPTO data (2005–2014) found that §103 was cited in about 66% of all first-office-action rejections, far more often than novelty or any other issue. This makes sense: it’s relatively rare to find a single prior art reference that identically anticipates a new invention (especially if the inventor and their attorney did a good job distinguishing it), but it’s very common for examiners to find a couple of references that, in combination, cover the elements.

Concrete Examples

Obvious combination: Suppose that smartphones were known to have a fingerprint sensor (prior art A) and that facial recognition unlock was known separately (prior art B). If you claim a phone with both fingerprint and face unlock working in tandem, an examiner might say it’s obvious to combine these two known security features, unless you can point to a surprising synergy or a technical hurdle overcome.

Non-obvious advance: Now imagine a new wireless communication protocol that achieves 10× the range of existing ones by a clever modulation technique. If nothing in prior art suggested that technique or the improvement, and it was not straightforward to achieve, that could be a non-obvious (inventive) step. Even if someone skilled might imagine boosting range, the specific way you did it yields unexpected results or overcomes a prejudice, making it non-obvious.

Secondary Considerations (Objective Indicia of Non-Obviousness)

When it’s a close call, U.S. law allows inventors to use real-world evidence to tip the scales toward non-obviousness. These are things that happened after the invention that imply it wasn’t obvious at the time:

- Commercial success: If the invention achieved significant market success, and importantly, that success is due to the merits of the invention (not just heavy marketing or a famous brand), it suggests the invention filled a need others couldn’t, implying non-obviousness

- Long-felt but unsolved need: Industry wanted a solution for years, and only this invention provided it

- Failure of others: Others tried and failed to solve the problem. The fact that it wasn’t solved until this invention hints that it wasn’t obvious

- Unexpected results: The invention works dramatically better than expected. For instance, a new drug formulation that everyone thought would be too unstable, but you found a way, and it’s unexpectedly effective with low side effects.

- Skepticism or “teaching away” in prior art: If experts or prior literature taught that your approach wouldn’t work or advised against it, then doing it and succeeding is strong evidence of non-obviousness (you went against conventional wisdom)

These factors often come into play in litigation (when someone is trying to invalidate a patent in court) because they require evidence. During initial patent examination, you typically rely mostly on arguments and experimental data in your application. But a savvy patent applicant can preemptively bolster the record: for example, by including data in the application that shows an unexpected improvement over prior art, or by noting in the background how prior attempts failed, thereby creating a narrative of non-obviousness.

A notable recent example is in the software field: patents on machine learning optimization techniques often hinge on unexpected performance improvements. If a new neural network architecture achieves 10x faster training time or 50% higher accuracy than standard approaches, and this wasn’t predictable from prior art, the patent is more likely to withstand obviousness challenges. The EPO and USPTO have both been especially stringent on obviousness in software patents, requiring clear evidence that the improvement wasn’t an obvious next step.

Bottom line: Inventive step/non-obviousness is somewhat subjective and can be the most challenging hurdle. Always ask yourself: If someone had all the pertinent prior art on their desk, would my invention be an obvious next move? If so, either the invention might not be patent-worthy, or you need to identify and emphasize what is counterintuitive or special about it. At Rapacke Law Group, we specialize in overcoming §101 and §103 rejections through strategic claim drafting and evidence-based arguments. We document any surprising effects or technical challenges you overcame during development. These details often become key to arguing non-obviousness successfully and securing strong patent protection.

Utility / Industrial Applicability: The Invention Must Work and Be Useful

The final core condition is often the easiest to satisfy. Still, it’s essential, especially in specific fields: your invention must have real-world use and actually perform as described. This requirement is called utility in the U.S. and industrial applicability in Europe and many other regions.

In plain terms, you can’t patent something that’s purely speculative, inoperable, or pointless. Patents are intended for useful inventions.

The U.S. Utility Standard

Under 35 U.S.C. § 101 (U.S.), the invention must be “useful,” which courts have interpreted to mean it has to have specific, substantial, and credible utility:

- Specific: The utility you claim for the invention must be particular to the invention, not a vague general utility that could apply to almost anything. (For example, saying “this chemical compound might be useful as a fertilizer, or a detergent, or maybe in treating diseases” is too broad; you need a particular use.)

- Substantial: There must be a real-world benefit that is not trivial. A toy or a novel game can be significant (entertainment is a legitimate utility). Still, something like “this compound changes color at a certain pH, which is interesting, but we don’t know any application for that” might be considered not substantial unless tied to a use.

- Credible: The asserted use must be believable to a person skilled in the art. You can’t claim a perpetual motion machine or a cure for all cancer without evidence. If it violates known scientific principles or is wildly implausible, the patent office will reject it for lack of credible utility.

For mechanical, electrical, or software inventions, utility is rarely a problem. If you invented a smartphone app for organizing photos, that would be useful on its face. Typically, examiners don’t question utility unless it’s not self-evident or there’s reason to suspect the invention doesn’t work.

The Trickier Cases in Chemistry and Biotechnology

New chemical or biological material: If you isolate a new chemical or biological material, you must identify a specific use for it. You can’t just say,y “we found a new protein, it probably has some role in cellular function.” Patent offices will ask: What exactly can you do with it? If you don’t know, you may fail the utility. A classic example is the case of Expressed Sequence Tags (ESTs) in biotech. In In re Fisher (Fed. Cir. 2005), scientists sought patents on snippets of gene sequences (ESTs) without knowing what the genes do, merely stating that the ESTs could be used as research probes. The court found no specific and substantial utility: the ESTs were simply a starting point for research, not an achieved invention with a known use. The patent was denied because, without knowing the gene’s function, the EST was like a mystery tool, maybe useful someday, but not yet shown to provide a concrete benefit.

New drug or biomedical invention: If you claim a new drug or biomedical invention, you typically need to show it has a real therapeutic or diagnostic use. For example, you synthesized a new compound. Great, but does it treat a disease or have some pharmacological activity? If you have in vitro data or animal study results indicating a specific effect (e.g., lowering blood glucose or killing cancer cells), that is often enough to establish utility. But if you just speculated “compound X might be useful to treat cancer” with no data or rationale, the examiner can object that it’s not “credible” or not “specific.” (One can’t just guess; there should be some scientific basis or experimental evidence.)

Inoperable inventions: If an invention as claimed would violate the laws of physics (like an actual perpetual motion machine claiming infinite energy), the USPTO will reject for lack of credible utility (and often also as not enabled). Another example: a time machine or a psychic wave communicator. Extraordinary claims require proof. Patent offices can require evidence that an invention works if it’s not something a skilled person would consider obviously workable.

Europe: Industrial Applicability

Under Article 57 EPC, an invention is industrially applicable if it “can be made or used in any kind of industry, including agriculture.” This is interpreted similarly: your invention must be capable of being made or used in practice. The EPO also requires that the application explicitly disclose the invention’s industrial applicability; otherwise, it will object to a lack of industrial applicability. This has caught some biotech applications off guard. For instance, the EPO famously objected to early gene-sequence patent applications that didn’t clearly state how the gene’s protein product was used.

Special Issues in Life Sciences

The utility requirement plays a gatekeeping role for things like genomics and pharmaceuticals:

Biomolecules: If you discover a new biomolecule (gene, protein, etc.), you should at least hypothesize a function and use, backed by some evidence if possible. E.g., “We identified a receptor protein and have data suggesting it’s involved in insulin signaling, so that it could be a drug target for diabetes.” That gives it a credible and specific utility.

Drug patents: You typically have some biological data. If you claim a new chemical compound, you might include experimental results showing it binds to a particular enzyme or has a specific effect in cell assays. Without that, both USPTO and EPO might say it’s just a chemical with no demonstrated use. (They might even say the invention isn’t fully enabled if no use is disclosed, since a person skilled in the art wouldn’t know how to apply it.)

Timing is essential: Utility is assessed as of the filing date. This means you cannot use data you generated after filing to post-rationalize utility. It has to be either in the application as filed or at least implicitly credible at that time. This came up during the COVID-19 pandemic, when companies filed patents on vaccine or drug candidates: they needed to include preliminary data (such as antibody responses in animal studies) to show credible utility in preventing or treating COVID-19, rather than just saying “this might work, trust us.”

The consequence of an invention lacking utility/industrial applicability is that it won’t get a patent (or, if it slips through the grant process, it could be invalidated later). This is somewhat rare compared to novelty or obviousness rejections, but it happens in fields like:

- Pharmaceuticals (where a broad claim might be invalidated if the patent doesn’t demonstrate that all claimed compounds have the promised utility; a recent Supreme Court case, Amgen v. Sanofi (2023), though technically about enablement, illustrated this by invalidating broad antibody claims where only a few examples were shown to work)

- Biotech research tools (like ESTs, or claiming a receptor without a known ligand or function)

- Theoretical physics devices (e.g., a claim for a warp drive; you’d have a hard time proving utility)

In summary, meeting the utility requirement is straightforward: make sure you explicitly state at least one useful purpose of the invention and that it’s plausible. If you have working examples or data, even better; include them. For most gadgets and software, the use is self-evident (examiners aren’t going to argue that a new machine or a computer process has no use if it clearly does something). But in cutting-edge fields, take care to explain why someone would want this invention and to demonstrate that it actually works for that purpose.

Other Important Conditions: Disclosure, Clarity, and Formal Requirements

Beyond the “big four” conditions (patentability criteria) (subject matter, novelty, inventive step, utility), patent laws impose additional requirements to ensure that the public receives a complete teaching of the invention in exchange for the patent monopoly. These often fall under the umbrella of patent quality or validity requirements, and they can be just as crucial. The two main ones are enablement (sufficiency of disclosure) and clarity (definiteness of claims). Failing these can doom a patent application or invalidate an issued patent, just as surely as lacking novelty or non-obviousness.

Enabling Disclosure & Written Description

In the U.S., 35 U.S.C. § 112(a) requires that the patent specification describe the invention in enough detail that a person of ordinary skill in the art can make and use the invention without undue experimentation. This is called enablement. It means “give a how-to guide for your invention. You don’t need to include step-by-step instructions for every variant, but you do need to provide sufficient information and examples so others can carry it out.

Section 112(a) also includes the written description requirement: the inventor must demonstrably possess the invention at the time of filing, which in practice means the specification must clearly describe the invention (particularly each claim) in a way that shows you had actually invented what’s being claimed, not just guessed or wished for it.

Key points:

- Enablement: Think of it as completeness. Did you disclose at least one way to perform the invention for each claim? If someone skilled reads your patent, can they implement it without having to invent something significant themselves? If they have to do extensive research or solve substantial problems to use your invention, then your patent may not be enabling.

- Written Description: This often comes up when claims are broad or amended. You must have support in the original filing for the full scope of what you claim. You can’t add new matter later. For instance, if you filed a patent on a species but then claim a genus, you must have indicated in your original filing that you contemplated that broader genus.

A famous modern case highlighting these requirements is Amgen Inc. v. Sanofi (2023) at the Supreme Court. Amgen had patents on a broad class of antibodies targeting a specific protein (PCSK9) to lower cholesterol. Still, they disclosed only a few example antibodies and essentially told scientists, “We have a method to generate more antibodies of this class; trust that it works.” The Supreme Court unanimously held the patents invalid for lack of enablement: the claims covered potentially millions of antibodies, but the patent didn’t enable making and using all of them except by undue experimentation (basically a trial-and-error fishing expedition). This case underscored that if you claim a broad territory, your disclosure must be commensurate with that breadth; a handful of examples can’t support sweeping claims if the field is unpredictable.

In Europe, similar concepts exist; for a U.S. perspective, see Andrew Rapacke, intellectual property attorney.

- Article 83 EPC: sufficiency of disclosure (analogous to enablement)

- Article 84 EPC: claims must beexplicitr and supported by the description (support by description is somewhat akin to the written description requirement)

Europe can be even stricter on some of these; for example, they often require that if you claim something broadly, the description should either have enough examples or reasoning to make it plausible across the scope.

Clarity and Definiteness of Claims

The claims of a patent define the legal scope of protection. They need to be clear and specific. In the U.S., §112(b) requires claims to “particularly point out and distinctly claim” the subject matter of the invention. If a claim is indefinite (meaning a skilled person cannot reasonably ascertain what it covers), the claim is invalid.

Examples of clarity issues:

- Using relative terms without a standard (e.g., “a readily portable device”: how portable is readily portable?). Unless the spec provides guidance (e.g., weight or size parameters), it’s unclear.

- Ambiguous phrasing or internal inconsistency in claims

- Functional claiming without sufficient structure (especially in software or means-plus-function claims; these can run afoul of definiteness if not properly supported)

During prosecution, examiners may issue §112 rejections if the claims are vague or overly broad, such that it isn’t clear what falls inside or outside the claim. For instance, claiming a range “between about 50 and 100 °C” could be questioned: what does “about” 50 mean? ±5? ±10? If it matters, it should be clearer.

Europe’s Article 84 is often invoked for a lack of clarity or support. If your claims include features not explained in the description, or if terms are not defined, the EPO may object.

Clarity is not usually a reason an invention fails to meet patentability requirements (you can often fix claim language during prosecution). Still, in litigation, indefiniteness can be a defense: a U.S. patent can be found invalid if a court deems a claim too ambiguous (after the Supreme Court’s Nautilus decision in 2014, the standard is that a claim must inform with “reasonable certainty” what is covered). In Europe, unclear claims cannot be granted or can be revoked in opposition.

Other Formal Requirements

There are various formalities:

- Unity of invention: You can’t claim unrelated inventions in one patent application. If you do, the office will ask you to restrict or split into divisional applications.

- Best mode (U.S.): The U.S. used to enforce that you disclose the best way you know to practice the invention. Post-AIA, failing to disclose the best mode is no longer grounds to invalidate a patent, but you are still supposed to include it if there is one.

- Drawings, format, etc.: Patent offices have rules about including drawings when necessary for understanding, and formatting the application in specific ways. For example, biotech patents often require sequence listings in a specific electronic format for gene or protein sequences.

These don’t usually impact patentability judgments, but you must comply to get a grant.

Why These Requirements Matter

They ensure the patent system’s bargain is fulfilled: the public gets access to the new technology (so others can build on it or design around it), in exchange for the inventor receiving limited exclusivity. A patent that hides the ball (insufficient disclosure) or has fuzzy boundaries (unclear claims) fails that bargain.

Indeed, a high percentage of patent litigation cases involve invalidity arguments based on lack of enablement or written description, especially in biotech/pharma, where these issues are rigorously examined. For example, an internal EPO audit found that about 4.6% of reviewed grants had issues with added matter (a related concept to written description). In opposition proceedings, nearly half of the challenged European patents are revoked in full (often because the claims are found not novel or not supported by the original disclosure). Those numbers show that getting a patent granted is not the end; it must also withstand scrutiny later, which is why solid disclosure and precise claims from the start are crucial.

Practical example: Let’s say you created a software algorithm that matches buyers and sellers more efficiently. If your patent application just states a high-level goal (“match buyers and sellers using a computer network”) but doesn’t detail how (the algorithm, the technical implementation), it could be rejected for lack of enablement or written description: you haven’t actually taught the invention, just stated a wish. This happened in some early “Internet patents” that filed broad claims without technical substance; many were later invalidated. Always ensure you include concrete embodiments and implementation details for your inventions, especially for broad concepts.

How to Assess Whether Your Idea Meets the Conditions of Patentability

Before investing significant time and money into a patent application, it’s wise to conduct a realistic assessment of your invention against these conditions. At Rapacke Law Group, we offer comprehensive patentability searches at a transparent fixed fee, and if our search finds your invention isn’t novel, we provide a 100% refund, no questions asked. This early investment (typically far less than full application costs) can help you avoid pursuing a hopeless case or identify areas to strengthen before filing. Consider this a patentability feasibility study that de-risks your entire IP strategy.

A Practical Pre-Filing Checklist

1. Patent-Eligible Subject Matter Check:

- Does your invention fall into a statutory category (process, machine, manufacture, composition of matter)? For most inventions, yes.

- If it’s a process, is it tied to a machine or a transformation, or is it otherwise technical? If it’s purely an abstract process (e.g., a mental exercise or a business transaction), consider how to give it concrete form.

- Does it risk being labeled a mere abstract idea or natural phenomenon? If so, brainstorm ways to emphasize a technical application. (For software, that might mean focusing on system architecture or technical performance gains. For a biotech discovery, frame it as a specific application, like a drug or a diagnostic test, not just a discovery of a biological correlation.)

- Red flag: If you’ve essentially got a scientific principle or a creative concept with no implementation, you likely need to do more development or at least consult on claim strategy.

2. Novelty Check (Prior Art Search):

- Search, at least a basic one. Use Google Patents, the USPTO database, or hire a professional search firm to see what’s out there similar to your invention.

- Look at both patent literature and non-patent literature. Sometimes the most significant threat is not another patent but an academic paper or a product manual from a few years ago.

- Try different keywords and think internationally: prior art isn’t limited to English or to your industry’s journals.

- If you find something identical to your idea, that’s a big problem (novelty killer). If you see something very close, note the differences.

- Remember, your own disclosures (papers, presentations, etc.) count too (unless very recent and within the U.S. grace period). Gather those dates if applicable.

- If you identify potentially novelty-destroying art, you might pivot: Can you narrow or tweak your concept to make it more distinctive? Or consider not patenting but using trade secrets if novelty is blown, but the invention isn’t easily reverse-engineered.

3. Non-Obviousness Assessment:

- Identify the closest prior art (perhaps one reference closest to your core idea).

- List the differences between your invention and the prior art. What new features or steps are you adding?

- For each difference, ask why a skilled person wouldn’t have done that already. Look for justification of non-obviousness:

- Does your invention solve a problem that others overlooked or couldn’t solve? (State what that problem is; it frames the inventive step.)

- Are there technical hurdles you overcame? (E.g., “previous attempts to add feature X caused a system crash, but we discovered a workaround.”)

- Are the components you combined taught in different fields that a person might not readily mix? (Cross-disciplinary leaps can be non-obvious.)

- Any surprising results? (If yes, definitely highlight those in the application. E.g., “Surprisingly, adding ingredient Y not only did X, but also improved Y by 300%, contrary to expectation.”)

- Also consider: if you were an examiner, what references might you combine to reject your own invention? If you can think of some, that’s good; you’re anticipating the obviousness argument. Then you can craft your description to distinguish from those combinations or emphasize a teaching approach.

- Realistically, if your invention is simply one minor modification over the known art (like changing a component’s material from plastic to metal), you need either a good unexpected effect or else it is obvious. It doesn’t mean you abandon the patent, but you might narrow the claims to a configuration in which that change yields a new benefit, etc.

4. Specific, Credible Utility:

- Ask, “What can this invention be used for, concretely?” Write down a clear statement: “This invention [device/process] is used for [specific purpose].”

- Is that purpose substantial (not trivial or frivolous)? Usually, yes, but if it’s a scientific curiosity, you need to articulate a practical use.

- Make sure you can either demonstrate that it works (with data or a prototype) or that it’s based on sound science. If your invention involves a new principle, do you have a working example or at least calculations?

- Especially for biotech: identify at least one real-world application and, ideally, provide preliminary evidence. If you have a new compound, what does it treat, or what product could it be used in? If you have a new genetic construct, what can it produce or detect?

- If you can’t think of a specific use, you probably aren’t ready to patent it (and patent offices won’t allow a “research plan” to be patented).

5. Enablement and Documentation:

- Even before writing the application, gather your technical data, drawings, and experimental results. If something has not yet been built, consider building a prototype or running proof-of-concept tests, especially if the invention is complex or could be met with skepticism.

- Ensure you know the best way to carry out the invention (and plan to describe it). If there are alternatives, note those too.

- If your invention is software, code, or flowcharts, they can be handy for showing that you actually implemented the method (and can be described in the patent).

- For mechanical or electrical inventions, detailed CAD drawings or circuit schematics are gold for patent drafting.

- If it’s a process, run through it step by step and note any crucial conditions or ranges (temperatures, concentrations, etc.).

6. Avoid Premature Disclosure:

- This is more of a project management tip: if you haven’t yet publicly disclosed, keep it that way until filing. Use confidential channels.

- If you absolutely must disclose (for example, to pitch to investors or to show at an expo), file a provisional application first. The provisional doesn’t need to have formal claims and can often be prepared more quickly; it locks in a filing date.

- Mark materials as confidential if appropriate, and educate your team not to inadvertently publish anything (including on company websites or personal LinkedIn/blogs) before the patent filing.

7. Consider the Type of Protection:

- We’ve focused on utility patents (technical inventions). But recall, there are design patents (for ornamental designs of articles) and plant patents (for new asexually reproduced plant varieties) in the U.S., and similar design protections in other countries.

- Sometimes an innovation is primarily in how something looks rather than how it functions. For example, a unique smartphone shape or a new car grille might be within the scope of a design patent. Design patents have different criteria (novelty and non-obviousness based on visual appearance).

- Or if you developed a new variety of rose or apple tree, a plant patent or plant breeders’ rights might be the way to go.

- If your idea isn’t quite a functional/technical advance but is creative (such as a purely artistic creation, a game rule, or a presentation format), it might fall outside patentability altogether; perhaps other IP, such as copyright or trademark, is relevant. For instance, a new board game’s gameplay can’t be utility-patented (it’s more of a scheme for playing a game, which is usually not patentable subject matter on its own). Still, the artwork or brand can be protected via copyright/trademark.

After running through this checklist, you’ll have a better sense of your case’s strengths and weaknesses. You might discover that while your core concept is excellent, you have a prior publication by someone that is worryingly close (so you might focus your claims on a particular improvement to distinguish it). Or you might realize you need to gather more data to prove an aspect of the invention works (maybe delay filing until you have that, if timing allows).

Seeking Professional Advice

For high-stakes inventions, getting a professional patentability opinion from an experienced patent attorney is essential, not optional. At Rapacke Law Group, we offer transparent, fixed-fee patentability searches with a guarantee: if our comprehensive search finds your invention isn’t novel, you receive a 100% refund. We can perform thorough prior art searches across U.S. and foreign patents, published applications, and technical literature, then provide an informed analysis of whether your invention is likely to clear all patentability hurdles and how to frame it strategically. This typically represents a small upfront investment compared to the $15,000–$25,000+ cost of drafting and filing a complete utility patent application. It prevents you from spending heavily on an application that can’t succeed.

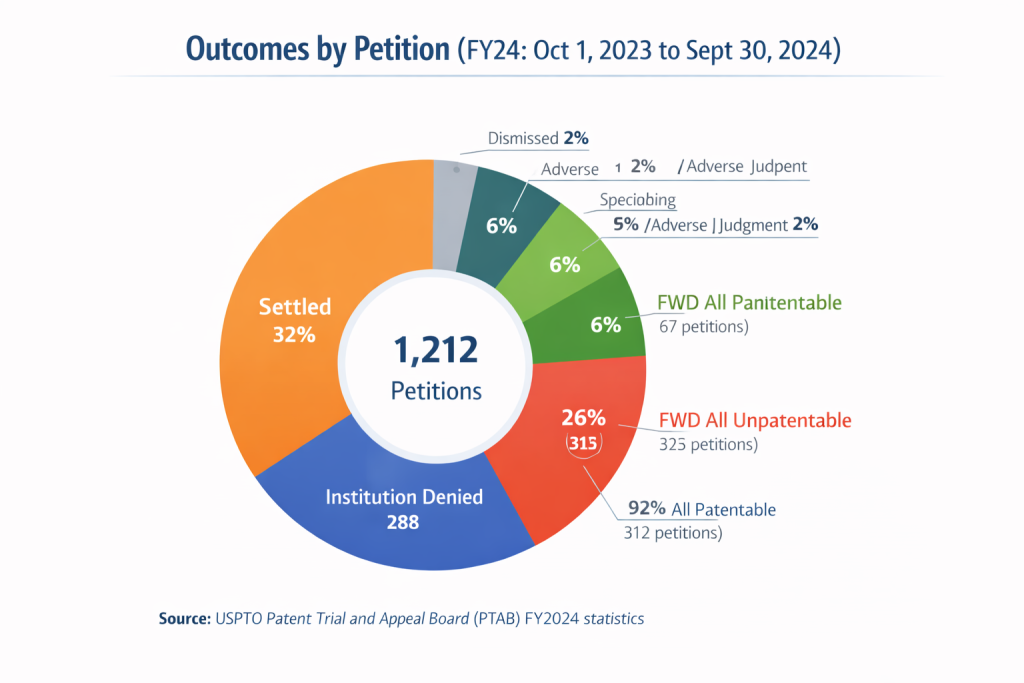

Finally, remember that even if you obtain a patent, it’s not the end of the story. Patents can be challenged in various venues (through the USPTO’s PTAB trials or in court during infringement litigation). While roughly half of patents fully adjudicated in U.S. courts have at least some claims found invalid, this statistic reflects selection bias; only the most questionable patents proceed to full litigation. Well-supported, strategically drafted patents with solid documentation rarely face these challenges.

Figure 2: Outcomes of PTAB petitions in FY2024 show that full invalidation is far from guaranteed. Only 26% of petitions resulted in all claims being found unpatentable, while many cases were denied institution, settled, or resulted in partial or no invalidation.

This is why working with experienced patent counsel from the outset is critical: proper claim drafting, comprehensive prior art analysis, and thorough documentation help ensure patents withstand scrutiny. At RLG, our approach focuses on building enforcement-ready patents from day one, not just securing grants that collapse under challenge.

Key Takeaways

- The four core conditions of patentability are: (1) patentable subject matter, (2) novelty, (3) inventive step/non-obviousness, and (4) industrial applicability/utility. These form the universal baseline for patent grants worldwide.

- These requirements are embodied in laws such as 35 U.S.C. §§ 101–103 (in the U.S.) and EPC Articles 52–57 (Europe), and are reinforced by treaties such as TRIPS, which mandate that patents be granted only for inventions that are new, inventive, and useful.

- Subject matter eligibility ensures you can’t patent abstract ideas, natural laws, or purely mental/business schemes without a technical application. Understanding the latest guidelines (e.g., the USPTO’s 2019 guidance, which reduced abstract idea rejections by ~25%) and legislative trends (such as the proposed Patent Eligibility Restoration Act) can help frame your invention for approval.

- Novelty means absolutely no public disclosure of the same invention before you file. Avoiding premature disclosure is critical: use NDAs and consider provisional applications early. The U.S. gives you a 1-year grace for your own disclosures, but most other regions don’t; a public reveal can instantly forfeit your foreign patent rights.

- Non-obviousness is often the most challenging hurdle: you must show your invention is not an obvious combination or variation of existing knowledge. Examiners will combine multiple references to argue that it would have been obvious. Emphasize unexpected results, solve long-standing problems, and highlight differences that a skilled person wouldn’t readily notice. Keep evidence of any surprising advantages; even partial success, like improved efficiency, can counter an obviousness rejection.

- Utility (or industrial applicability) requires a real-world use. Especially in biotech/pharma, clearly demonstrate specific, substantial, and credible utility, supported by data or a sound scientific rationale. Don’t claim more than you can help; patents on broad biological concepts without evidence are likely to be invalid (as seen in In re Fisher for ESTs and Amgen v. Sanofi for broad antibody genus claims).

- Enablement and clear disclosure are as vital as the invention itself. A patent is only as strong as its specification: it describes how to make and use the invention thoroughly. Broad claims demand broad support. Vague claims or insufficient detail can lead to rejection or later invalidation. Recent court decisions are enforcing this strictly (e.g., the Supreme Court in 2023 requiring that broad claims be fully enabled across their scope).

- Do your homework before filing: conduct prior art searches and analyze the differences between your invention and prior art. An internal study or a professional patentability opinion can illuminate risks (like close prior art or obviousness concerns) early on. With patents costing tens of thousands to obtain and maintain, a sanity check is worth it.

- Work with an experienced patent attorney who specializes in your technology area to navigate nuances such as claim wording, jurisdictional differences (U.S. vs. Europe), and strategic decisions (continuing applications, international filings under the PCT). At Rapacke Law Group, we focus exclusively on patents and trademarks for tech innovators, particularly in software, SaaS, and AI. Each field has its own wrinkles in patent law; our specialized expertise helps tailor your application to avoid common pitfalls while maximizing the scope of protection and enforceability.

- Patenting is a marathon, not a sprint. Even after you file, expect back-and-forth with examiners. Roughly 90% of applications get at least one rejection; persistence (with reasoned arguments or claim amendments) often pays off. But also know when to fold: if an examiner has substantial grounds (like a knockout prior art reference), it might be wise to narrow claims or abandon if the invention isn’t distinguishable.

- Keep an eye on post-filing requirements: To actually get the patent and keep it, you’ll need to respond to office actions, pay issue fees, and later pay maintenance fees (in the U.S., at 3.5, 7.5, and 11.5 years after grant). Ensure you budget for these and docket the deadlines.

Your Next Steps to Patentability Success

You now understand the four core conditions every patent must meet, but understanding requirements and successfully navigating them are two different challenges. The difference between a strong patent application that clears all hurdles and a weak one that gets rejected often comes down to strategic framing, thorough documentation, and expert claim drafting from the start. Weak patents invite challenges from competitors who see opportunities to invalidate your protection. Strong patents (properly researched, strategically drafted, and thoroughly documented) create genuine deterrence because the cost and risk of challenging a well-constructed patent far outweigh the benefit of trying to design around it.

Here’s the urgency you’re facing: every day that passes without filing protection is a day your competitors could be developing similar solutions. In the first-to-file system, the race goes to the swift, not the inventor who waits until everything is ‘perfect.’ And if you’ve already publicly disclosed your invention at a conference, in a blog post, or at a demo day, you may have just weeks left to file before losing international patent rights permanently. Many founders discover this too late, after their crowdfunding campaign or Product Hunt launch has destroyed their ability to secure protection in key markets.

Here’s what you should do right now:

- Schedule a Free IP Strategy Call with the Rapacke Law Group team to evaluate your invention’s patentability against all four core conditions and develop a strategic protection plan tailored to your specific technology and business goals.

- Conduct a comprehensive prior art search before investing in a complete application. At RLG, we offer this as a fixed-fee service with a guarantee: if our search finds your invention isn’t novel, we refund 100% of your investment, no questions asked.

- Document your invention thoroughly right now: technical specifications, prototypes, test results, competitive advantages, everything that demonstrates why your solution is new, non-obvious, and useful.

- If you’ve already disclosed publicly, calculate your deadline immediately. You likely have 12 months (U.S. only) or 0 months (international) remaining to file a provisional application.

- Review your SaaS legal documentation if you’re a software founder. Check out our SaaS Agreement Checklist to ensure your broader IP strategy is covered while you pursue patent protection.

The path from innovative idea to enforceable patent requires clearing each of these hurdles with precision. Strong patent protection isn’t just about getting a grant; it’s about building intellectual property that withstands challenges, deters competitors, and increases your company’s valuation when raising funds or positioning for acquisition. Every dollar invested in a proper patent strategy early returns multiples in competitive advantage and business leverage later. At Rapacke Law Group, our fixed-fee model means you know precisely what strategic patent preparation costs upfront, and our patentability search guarantee means you risk nothing if we determine your invention isn’t novel.

At Rapacke Law Group, we specialize in helping SaaS founders and tech innovators navigate the complex patentability landscape with our fixed-fee, transparent pricing model. Here’s what sets our patentability assessment services apart:

- FREE strategy call with our patent team to assess your invention’s patentability against all four core conditions.

- Comprehensive patentability search covering U.S. and foreign patents, published applications, and technical literature.

- Experienced U.S. patent attorneys who specialize in software, AI, and tech patents, not generalists or offshore contractors.

- One transparent flat fee covering the entire patentability search process, including detailed analysis and strategy consultation.

- 100% refund guarantee if our search finds your invention is not novel, we risk our fee, so you don’t risk yours.

- Your choice: full refund OR another complimentary search if patentability issues emerge.

- Strategic guidance on how to frame your invention to maximize allowance probability if the search is favorable.

Don’t let competitors copy your innovation or watch your patent rights evaporate due to premature disclosure. The cost of inaction far exceeds the investment in proper protection.

About the Author

This article was written by Andrew Rapacke, Managing Partner and Registered Patent Attorney at Rapacke Law Group. Andrew specializes in software patents, AI innovation protection, and IP strategy for SaaS startups and tech companies.

Connect with Andrew on LinkedIn or follow RLG on Twitter/X (@rapackelaw) and Instagram (@rapackelaw).

To Your Success,

Andrew Rapacke

Managing Partner | Registered Patent Attorney

Rapacke Law Group