Most business owners think trademarks only protect logos and brand names. They’re missing roughly 90% of what’s protectable and leaving their most valuable assets exposed.

The numbers prove it: as of Q3 2025, over 3.4 million trademarks are registered in the U.S. alone, yet countless businesses operate without protecting distinctive elements such as their product’s signature sound, unique packaging shape, or even recognizable scent. These are known as distinguishing features, and they play a crucial role in trademark protection by setting your brand apart from others. Trademarks can also protect non-visible signs such as sounds, scents, or colors, which serve as distinguishing features for brands. Meanwhile, trademark-intensive industries contributed nearly $7.0 trillion to U.S. GDP in 2019, underscoring the critical role of these protections in modern business value.

Here’s what most miss: trademarks and other IP assets now account for an estimated 90% of the market value of S&P 500 companies—a dramatic shift from just 17% in 1975. Your brand identifiers aren’t just legal protections; they’re likely your company’s most valuable assets, safeguarded by intellectual property rights that grant exclusive use and help maintain your competitive edge.

This guide reveals exactly what what does trademark cover, from traditional elements to surprising non-traditional marks most competitors overlook. A trademark must be a sign capable of distinguishing the goods or services of one business from another to qualify for protection. You’ll learn which elements qualify for protection, how to navigate the registration process with confidence, and why global trademark filings surged from 3.4 million to 11.6 million annually over the past decade, making early protection more critical than ever.

What Does Trademark Cover: Beyond Logos and Names

A trademark is a sign that distinguishes your goods or services from those of your competitors. It identifies the source of a particular good or service, ensuring consumers can associate your brand with specific offerings. It functions as a badge of origin—a unique identifier that builds consumer recognition and trust. But trademark protection extends far beyond what most business owners realize.

Studies show that consumers rely on trademarks as signals of quality and consistency, forming an emotional trust in brands. This trust translates directly into competitive advantage. When you secure trademark protection, you’re not just preventing copycats—you’re preserving the consumer confidence that drives revenue.

Trademark ownership confers the exclusive right to use the mark for registered goods or services, giving you legal recourse against unauthorized use. This exclusive right is a legal privilege that reinforces your control and legal standing. This exclusivity is crucial for establishing market position and protecting the reputation you’ve built. Through enforcement mechanisms such as cease-and-desist letters or, when necessary, lawsuits, you prevent marketplace confusion and safeguard your brand’s integrity.

The Expanding Scope of Trademark Protection

Global trademark applications worldwide surged from 3.4 million in 2009 to 11.6 million in 2023, reflecting growing recognition that brand protection is an essential business strategy. Even more striking: intangible assets, such as trademarks, rose from 68% of S&P 500 companies’ value in 1995 to approximately 90% by 2020.

This shift means your brand identifiers have become your primary business assets—making comprehensive trademark protection not optional, but essential for long-term viability. A strong trademark not only safeguards your brand but also significantly enhances brand recognition and fosters customer loyalty, giving your business a potent competitive edge.

Different Forms of Trademarks: What You Can Actually Protect

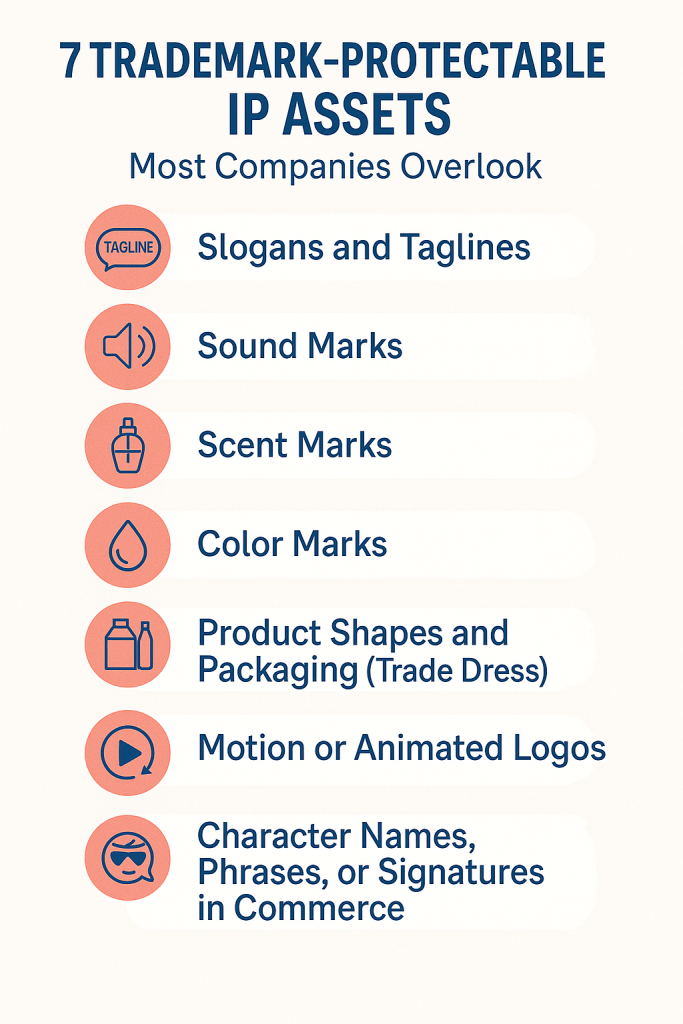

Trademarks encompass far more than logos and brand names. Understanding the full range of protectable trademark elements gives you strategic advantages that competitors often miss. Various types of signs or elements can constitute a trademark if they serve as effective brand identifiers.

Traditional Trademarks

These include brand names (words), logos, and slogans, the foundation of most trademark portfolios. Word marks are the most commonly registered type, since distinctive names and phrases serve as powerful brand assets. Examples include Nike’s name and swoosh logo, or McDonald’s “I’m Lovin’ It” tagline.

Sound Marks

Unique sounds or jingles associated with your brand can receive trademark protection if they signify your products or services. Sound marks are examples of non-visible signs that can function as trademarks. The NBC three-note chime is a registered sound trademark, as is the MGM lion’s roar. While less common than visual trademarks, hundreds of sound marks have been successfully registered worldwide, providing robust brand recognition in audio contexts.

Scent Marks

Yes, even distinctive smells qualify for trademark protection—though they’re rare. Hasbro trademarked the scent of Play-Doh modeling compound in 2018, described as a sweet, musky vanilla fragrance.

Only a limited number of scent trademarks exist in the U.S.—13 as of 2025. The bar is high: the scent must be non-functional (not essential to the product’s use) and consumers must link it to a single source. Play-Doh’s nostalgically linked smell cleared this hurdle precisely because of its strong brand association.

Colors and Shapes

Signature colors or product shapes can function as trademarks when strongly associated with your brand. Examples include Owens-Corning’s pink insulation material (the first color trademark registered in the U.S.) and the distinctive Coca-Cola bottle shape. The red soles of Christian Louboutin shoes represent another example of trademarked color plus product design.

These non-traditional marks require proving that consumers recognize the color or design as indicating your brand—what’s legally termed ‘acquired distinctiveness.’

Other Non-Traditional Elements

Trademark protection extends to motion marks (animated logos), holograms, textures, and theoretically even tastes. In entertainment, stage names and band names receive protection. Album titles or unique fictional character names can function as trademarks on merchandise or services.

The phrase “Let’s get ready to rumble!”—famously spoken by boxing announcer Michael Buffer—is a trademarked phrase, with its owner reportedly earning over $400 million by licensing it for games, merchandise, and promotions.

The key principle: Almost any distinctive brand signifier can potentially be protected, provided it identifies the source and isn’t functional.

What Qualifies for Trademark Protection

The range of protectable elements is broad, but distinctiveness and non-functionality remain crucial criteria.

Symbols and logos that consumers associate with your company (like Apple’s silhouette or Starbucks’ mermaid) are classic trademarks. Phrases and taglines can be trademarked if they’re unique, not common descriptive phrases. Apple successfully trademarked “There’s an app for that.”

Product shapes or packaging (trade dress) can be trademarked when distinctive. The Coca-Cola bottle’s curvy design is instantly recognizable and protected. The Zippo lighter’s shape and even building designs, like the Transamerica Pyramid’s silhouette, have received trademark protection.

Critical Limitations

You cannot trademark:

- Generic terms for product categories (like “Computer” for computers).

- Purely functional features (like a smartphone’s touchscreen).

- Elements not used in commerce as brand identifiers.

This flexibility means businesses can protect virtually any distinctive aspect of their brand identity—but only when it truly functions as a source identifier.

Service Marks: Protection Beyond Physical Products

A service is identical to a trademark, except it identifies services rather than physical goods. While “trademark” is often used broadly, service marks technically refer to marks for services, though legal protections are identical.

FedEx is known for shipping services, so FedEx functions as a service mark. Similarly, Google is a service mark for providing search engine services, and Netflix is a service mark for streaming entertainment.

Service businesses of all kinds—from consulting firms to airlines—rely on service marks to protect brand names and logos. You might see “SM” used to denote unregistered service marks, but in the U.S., “™” is commonly used for both until registration, after which “®” is used.

Service marks underscore that trademark law isn’t just about products on shelves—it equally covers businesses selling intangibles like financial services, legal services, entertainment, and hospitality. The test remains the same: is the name or logo distinctive for those services?

Examples of well-known service marks include UPS (delivery services), Visa (financial services), and Spotify (music streaming). Securing a service mark protects the provider’s reputation and goodwill, helping customers identify the service source and trust quality.

Collective Marks and Certification Marks

Beyond individual business trademarks, two special types serve collaborative or standardized contexts:

Collective Marks

Members of a group or organization use a collective mark to indicate membership or origin. The mark is owned by a collective organization (such as an association, cooperative, or union), and members are authorized to use it.

“Realtor” is a registered collective mark owned by the National Association of Realtors and used by its members, licensed real estate professionals. No individual owns “Realtor”—it signifies membership in that professional association and adherence to its standards.

Another example: the CPA designation (Certified Public Accountant), which is protected as a collective mark for members of the accounting profession in some countries. Collective marks are badges worn by groups that enhance members’ goods or services by conveying collective reputation or standards.

Certification Marks

A certification mark indicates that products or services meet specific standards or possess particular characteristics. The owner isn’t the producer of goods, but an authoritative body that sets standards.

The Woolmark logo is a certification mark indicating a product is made of 100% pure wool and meets quality standards set by The Woolmark Company. “USDA Organic” is a certification mark (administered by the USDA) for food/products produced according to organic farming standards.

Certification marks provide consumer assurance—when you see the mark, you know the product’s quality or characteristics have been independently verified. Other examples include the ENERGY STAR logo (certifying energy-efficient appliances) and the Fair Trade label (certifying ethical sourcing).

Critical distinction: Certification mark owners must allow anyone meeting the standard to use the mark—they cannot refuse qualified users. The owner typically doesn’t use the mark on their own goods or services (to avoid a conflict of interest as a neutral certifier).

Limitations and Exclusions: What You Cannot Trademark

Despite a broad trademark scope, significant limitations prevent overreach:

Trademark law cannot protect functional aspects—that’s what patent law is for. Functional features of a product, such as how it works or operates, are protected under patent law, not trademark law. This ensures that trademark law does not interfere with the domain of patent law, which is specifically designed to protect inventions and functional innovations.

Generic Terms

If a word is the generic name of goods, no one can own it as a trademark—doing so would prevent competitors from naming their products. You cannot trademark “Laptop” for computers or “Coffee” for coffee beans.

The term “Aspirin” was once a Bayer trademark but became generic for the drug; in the U.S., Bayer lost trademark rights to “Aspirin” as early as 1917, when it was deemed generic.

“Escalator” was originally a trademark of Otis Elevator Co., but a court ruled in 1950 that “escalator” had become generic for moving stairways, allowing others to use it.

Once a term is generic, anyone can use it—trademark law won’t create monopolies on words the public understands as product categories.

Descriptive Terms (Without Distinctiveness)

Words merely describing a quality, ingredient, function, or characteristic are not registrable unless they have acquired distinctiveness (secondary meaning) in consumers’ minds. For example, “Cold and Creamy” for ice cream would be purely descriptive and not inherently protectable.

Over time, if a descriptive term becomes uniquely associated with a single source, it can be registered with proof of secondary meaning. Many famous marks started descriptive but gained distinctiveness—Coca-Cola literally referred to two ingredients (coca leaves and cola nuts), but today consumers recognize it as a brand name. Apple (for computers) has a primary meaning (the fruit), yet, over decades of use, it has a strong secondary meaning as a tech brand.

Rule of thumb: You can’t trademark descriptive terms immediately; you must first use them and build recognition.

Geographic Terms and Personal Names

You generally cannot trademark geographic names simply describing where products come from (like “California Wines” for wine) because that would be descriptive of origin. Others in that location need to use the term.

Surnames or full names typically can’t be trademarked unless they acquire a distinctive brand association. McDonald’s is a trademark, but only because it has distinctiveness as a brand—McDonald’s was a surname, but now points to a particular fast-food chain. Trademark offices often reject last-name trademarks unless proof of secondary meaning is provided.

Deceptive, Misleading, or Functional Features

Any mark deceptively misdescriptive of products is barred. If a product feature or design is primarily functional (useful), it cannot be monopolized via trademark.

You couldn’t trademark a guitar body shape for acoustics because that would hinder competition by locking up a functional design. A company tried to trademark a peppermint scent added to a nitroglycerin spray (to mask its bitterness); it was deemed functional (making the medicine more palatable) and thus not registrable as a mark.

These limitations ensure trademark law doesn’t overreach—you can’t claim basic words everyone needs, nor inhibit fair competition by locking up useful product features.

Navigating Jurisdictional Differences

Trademark rights are generally territorial, meaning they apply only within the specific country or jurisdiction where the mark is used or registered. There’s no all-encompassing “global trademark”—you typically must secure protection country by country. For this reason, it is vital to apply for national trademarks to secure protection within specific countries before pursuing broader regional or international registrations.

First-to-Use vs. First-to-File Systems

The United States (and a few others, such as Canada and Australia) follow a first-to-use system—the first party to use a mark in commerce gains rights, even without registration. In contrast, most of the world (including the European Union, China, and Japan) follows a first-to-file system, in which registration is mandatory to obtain rights, and priority goes to the first filer.

Critical implication: In first-to-file countries, even if you’ve used a mark earlier, someone who registers it before you might secure the rights. U.S. businesses expanding abroad must be careful—others could claim unregistered marks in first-to-file countries.

Use Requirements and Protection Scope

In first-to-use countries like the U.S., you must have actual use in commerce to complete registration (or at least bona fide intent to use, followed by proof of use). In first-to-file countries, you often don’t need prior use to register—you can register and start using immediately.

However, many jurisdictions require trademarks not to lie entirely idle. After typically 3-5 years, unused trademarks can be challenged and removed for non-use.

Classification and Fee Systems

Nearly all countries use the Nice Classification (45 classes of goods/services) to organize trademark registrations. But some have single-class application systems (one class per application), while others allow multi-class filings (one application covering many courses), which affects strategy and costs.

Real-world example: Burger King couldn’t use its name in Australia at first because an Australian shop had trademarked it, so it operates as “Hungry Jack’s” there. Such scenarios highlight that having a trademark in one country doesn’t automatically grant rights in other countries—you must check and secure each critical market.

The Trademark Registration Process: Step-by-Step

The trademark registration process in the United States takes around 8-12 months (or more) from start to finish. Here’s what to expect:

1. Pre-Filing Clearance and Decision

Before filing, determine if registration is appropriate and check availability. The USPTO received over 767,000 applications in 2024, so thorough clearance searches (often done by trademark attorneys) can save you from filing marks that get rejected or infringe existing rights.

2. Submitting the Application

File your trademark application with the USPTO (or relevant national office). You’ll need to:

- Specify the mark (name/logo/etc).

- Identify goods/services covered (classified under Nice classes).

- State your basis (actual use or intent-to-use).

- Pay filing fees ($250-$350 per class in the U.S.).

Once filed, you receive a filing date, and the application is assigned to an examining attorney.

3. Examination by the Trademark Office

After several months, an examining attorney reviews your application for compliance with trademark law. They check for conflicts with existing marks (likelihood-of-confusion analysis) and statutory bars (descriptiveness, surnames, etc.).

Approximately 70% of U.S. applications receive some form of initial refusal or office action—commonly citing likelihood of confusion with existing marks or descriptiveness issues.

4. Response and Office Action Cycle

You have an opportunity to respond to any Office Action. The response deadline for pre-registration Office Actions is now 3 months (with an optional extension), not 6 months as previously. You might argue against cited conflicts, submit evidence of acquired distinctiveness, disclaim generic portions, or make required amendments. About 10% of refused applications are appealed to the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (TTAB).

5. Publication for Opposition

Once a USPTO examining attorney approves your application for publication, your mark is listed in the Trademark Official Gazette (TMOG) — a weekly USPTO publication that gives public notice of pending registrations. From the publication date, any party who believes the registration may harm them has 30 days to file a Notice of Opposition or request an extension of time to oppose.

Formal oppositions are relatively uncommon compared to total publications — practitioner estimates suggest that only a small percentage (roughly 2–3 %) of published marks face opposition. However, oppositions do arise, particularly with high-profile brands or in industries with active trademark enforcement.

Monster Energy Company is frequently active in TTAB opposition proceedings, particularly against marks featuring ‘Monster’, ‘Beast’, or claw-style designs, to protect its brand. While it does not always prevail, its litigation record shows a pattern of aggressive trademark enforcement.

6. Registration (or Notice of Allowance)

If no opposition is filed (or opposition is resolved in your favor), the USPTO issues a Registration Certificate for use-based applications. For “intent-to-use” applications, the USPTO issues a Notice of Allowance, giving you a window (6 months, extendable) actually to use the mark and submit proof before registration issues.

Registration benefits include: nationwide notice and presumed rights dating to your filing, ability to use the ® symbol, potential statutory damages in counterfeiting cases, and a basis for foreign filings.

Maintaining and Enforcing Trademark Rights

Once registered, trademarks can last indefinitely—but only with proper upkeep and vigilant enforcement. Trademark registration terms are 10 years, renewable every 10 years indefinitely. This means that trademark registrations can be renewed indefinitely as long as all renewal requirements are met.

Duration and Renewals

In many jurisdictions (including the U.S.), trademark registrations are valid for 10 years, renewable every 10 years indefinitely. The U.S. also requires a mid-term filing between the 5th and 6th year after registration to confirm the mark is still in use. While some registrations lapse due to business changes or discontinued brands, maintaining your registration is straightforward with proper calendar management. Many trademark registrations are not maintained through their first ten-year renewal. While the USPTO does not publish exact renewal-rate statistics, practitioners note that a significant portion of registrations—often estimated at around half—lapse at the ten-year mark because owners fail to file the required maintenance and renewal documents.

This reflects normal business turnover and the fact that many marks are discontinued, rebranded, or no longer in use over time.

Action step: Docket these deadlines. Missing a renewal means your registration lapses, and someone else could swoop in.

Continuous Use

Trademark rights (especially in common law countries) hinge on use. A mark that isn’t used can be vulnerable to cancellation for abandonment. Most countries allow others to petition for cancellation after a few years of non-use (typically 3 years). Maintaining rights means actively using the mark in commerce on registered goods/services.

Monitoring and Policing

Registering your mark is only part of the protection—you also need to monitor for unauthorized use and infringement. Trademark owners often set up watch services or alerts to catch when others use similar names or logos.

Several thousand trademark lawsuits are filed in U.S. federal courts each year (about 3,700 in recent statistics), often by brand owners seeking to protect their marks. If you find an infringer, a cease-and-desist letter is the typical first step. Many disputes end here with the infringer voluntarily rebranding.

Strategic enforcement protects your brand value and market position.

The federal court plays a crucial role in adjudicating these trademark disputes and establishing important legal precedents that shape trademark law. If you find an infringer, a cease-and-desist letter is the typical first step. Many disputes end here with the infringer voluntarily rebranding.

Preventing Dilution and Genericide

High-profile companies are known to be especially aggressive in litigating to protect their brand names. Enforcement isn’t only about stopping direct competitors—if you own a famous mark, you also want to prevent dilution (uses that blur or tarnish brand distinctiveness, even in unrelated fields).

Some companies run ad campaigns or usage guides to preserve brand identity—Xerox famously urged people to say “photocopy” instead of “xerox” as a verb. This prevents marks from becoming generic like “aspirin” or “thermos.”

Quality Control for Licensing

If you license your trademark to others (franchises, manufacturers making branded merchandise), you must maintain quality control. Trademark law requires owners to control the nature and quality of goods/services under the mark—failing to do so (“naked licensing”) can jeopardize your rights.

In U.S. law, after 5 years of registration and continuous use, you can file for incontestable status, which limits particular challenges to your mark. But incontestability can be lost if the mark becomes generic or if you don’t enforce against specific uses.

Bottom line: Trademark registration isn’t “set it and forget it.” You must renew on schedule, use consistently, and guard against misuse. The relatively low cost of a cease-and-desist letter can save you from bigger problems down the road.

International Trademark Protection: The Madrid System

For businesses operating internationally, the Madrid System, administered by WIPO (World Intellectual Property Organization), allows trademark owners to seek protection in multiple countries by filing a single “international” application. As of 2025, the Madrid Union comprises 115 member countries, representing a total of 131 countries.

How Madrid Works

You file an international application through your home country’s trademark office and designate other member countries where you want protection. Rather than hiring local lawyers in multiple countries and filing separate applications, you can file one application (in one language, with one set of fees in Swiss francs) to cover those countries.

Cost advantage: This significantly reduces costs and administrative burden compared to filing country-by-country.

National Examination Still Applies

Importantly, an international registration under the Madrid Protocol doesn’t guarantee automatic approval in all countries. Each designated country will examine the trademark under its own laws (over roughly 12-18 months). If a local office refuses protection, that particular designation will fail unless you overcome the refusal.

Madrid is a filing mechanism, not substantive harmonization—you still must comply with local laws, but you avoid multiple separate filings.

Central Management

Once you have an international registration, it’s easier to manage changes. Suppose you need to record ownership changes, address changes, or renew Madrid registrations (which are due every 10 years). In that case, you can do so centrally through WIPO for all designated countries at once.

Practical Example

Suppose you register a trademark in the U.S., then want protection in Europe, Japan, Canada, and Australia. Using Madrid, you file one international application (based on your U.S. registration) and designate EU, JP, CA, and AU. Each office examines the application. The EU and Japan may approve without issue; Canada issues an office action on descriptiveness, and Australia approves. You respond via a Canadian agent and succeed. Now you have protection in all four jurisdictions under one international registration.

Important note: Your home (“basic”) application/registration must remain in force for at least 5 years. If canceled within 5 years, the international registration is canceled in all countries (preventing gaming the system). After 5 years, the international registration becomes independent.

More than 80% of world trade is represented by Madrid member countries, making this system invaluable for managing trademarks internationally in today’s globalized market, where brands transcend borders more than ever.

Common Issues and Challenges Trademark Owners Face

Remember that approximately 70% of trademark applications receive initial refusals, often due to conflicts with other trademarks. As a brand owner, you need to watch not only for blatant counterfeits but also sound-alike or look-alike names that could erode your brand.

Monster Energy has become notorious for opposing even remotely similar “Monster” formative marks to prevent brand dilution. The challenge is striking a balance—you must enforce to keep your mark strong, but avoid appearing as a bully by overreaching.

Trademark Dilution for Famous Marks

Famous trademarks (Nike, Coca-Cola, Google) face dilution—unauthorized uses that don’t necessarily confuse consumers about source but blur or tarnish the mark’s uniqueness. Many jurisdictions provide legal remedies specifically for the dilution of well-known marks.

Famous brand owners also contend with marks being used as generic terms (like “Google” as a verb). Companies actively monitor how their brands are used in the media and sometimes engage in public education to avoid genericide.

Counterfeiting and Piracy

In specific industries (fashion, luxury goods, electronics), counterfeit products are a massive problem. Trademark owners must work with law enforcement and customs agencies, or use civil enforcement, to stop counterfeit goods from directly copying their trademarks—an ongoing global battle.

Cybersquatting and Online Infringement

In the digital age, challenges include domain name squatters (people registering domains containing trademarks to ransom or divert traffic) and unauthorized use on e-commerce or social platforms. Specific processes, such as the UDRP (Uniform Domain-Name Dispute-Resolution Policy), exist to recover domains from cybersquatters.

Companies must police online marketplaces for trademark infringement—often requiring dedicated teams or external services due to the internet’s scale.

Industry-Specific Challenges

Some sectors have particular trademark dynamics. In entertainment and sports, trademarks are crucial for merchandising and sponsorships.

The global licensed sports merchandise market is estimated at $36-37 billion in 2024 and is growing steadily. Sports teams trademark their names, logos, and even colors—not just to protect their brands but because licensing merchandise is a massive source of revenue. Teams vigilantly enforce their marks against unlicensed fan gear.

In tourism, regions use trademark slogans to promote tourism and control their use. “I ❤ NY” (I Love New York) is a trademarked slogan/logo owned by New York’s tourism department since 1977, and unauthorized use on merchandise is legally pursued.

Global Consistency vs. Local Adaptation

Brands expanding globally face the challenge of whether to use a single trademark worldwide or adapt to local languages/cultures. Some brand names don’t travel well due to meaning or pronunciation issues, or because someone local already has a similar mark—forcing rebranding in specific markets (like Burger King as Hungry Jack’s in Australia).

Your Next Steps to Trademark Protection Success

Understanding what trademarks can protect is the first step. Taking action to secure those protections is what separates thriving brands from those that lose market share to competitors or copycats.

The bottom line: A weak trademark strategy helps your competitors. A strong one deters them. When you fail to register and enforce your trademarks properly, you’re inviting others to dilute your brand value, confuse your customers, and chip away at the goodwill you’ve worked hard to build.

The stakes are real: Every day without proper trademark protection puts you at risk. In first-to-file countries (most of the world), someone could register your brand name before you do, locking you out of entire markets. In the U.S., common law rights exist but provide limited protection compared to federal registration. Your competitors are watching—and opportunistic trademark squatters are watching, too. Delay means lost revenue, diminished market control, and expensive legal battles to reclaim what should have been yours from the start.

Here’s what to do right now:

- Schedule a Free Trademark Strategy Call with our trademark concierge team. We’ll evaluate your brand’s protectability, identify potential conflicts, and develop a comprehensive protection plan tailored to your business goals—whether you’re protecting a product name, logo, slogan, or non-traditional mark like a signature sound or color.

- Conduct a comprehensive trademark clearance search before investing in branding, product launches, or marketing campaigns. Discovering conflicts early saves you from costly rebranding and potential infringement liability down the road.

- File strategically across all relevant trademark classes for your current products/services and reasonably foreseeable expansions. The Nice Classification system’s 45 classes mean many businesses need multi-class protection to safeguard their brands fully.

- Develop an international filing strategy if you operate globally or plan to expand. With 80% of world trade represented by Madrid System member countries, coordinating international protection early prevents foreign trademark squatting and preserves your global brand consistency.

Why partner with Rapacke Law Group? Unlike hourly billing that incentivizes delays, our fixed-fee model aligns our success with yours. You know precisely what you’ll invest upfront, with no surprise bills. Plus, our industry-leading guarantee means you get your trademark approved or pay nothing—we’re that confident in our process and expertise.

Your trademark is a living asset that grows in value as your business succeeds—but only if properly protected and enforced. Companies with comprehensive trademark strategies enjoy stronger market positions, higher brand valuations, and greater competitive leverage—the investment you make today in securing your trademark rights compounds exponentially as your brand recognition grows.

Don’t let uncertainty or delay cost you your most valuable business asset. Schedule your free strategy call now and protect what you’ve built.

The RLG Guarantee for Trademark Registration

At Rapacke Law Group, we stand behind our work with an industry-leading RLG Guarantee:

Get your trademark approved or pay nothing. We guarantee it.

**We’re so confident we’ll get your mark approved that if your trademark gets rejected, we’ll issue a 100% refund. No questions asked.

What’s included:

- FREE strategy call with our trademark concierge team to evaluate your brand and develop a protection plan.

- Experienced U.S. attorneys lead your registration from start to finish—no paralegals, no outsourcing.

- One transparent flat-fee covering the entire trademark application process, including office action responses.

- Unlimited office action responses to overcome USPTO objections and secure approval.

- Full refund if the USPTO ultimately denies your trademark application*.

- Complete refund or additional searches if your brand has registerability issues—your choice*.

Unlike hourly billing that incentivizes delays and maximizes costs, our fixed-fee model aligns our success with yours. You know precisely what you’ll invest upfront, with no surprise bills or mounting legal fees.

Contact us today to protect your brand with confidence.

*Terms and conditions apply. See our website for complete guarantee details.

Summary: Protecting Your Most Valuable Business Asset

Trademarks are vital tools for distinguishing and protecting brands in today’s competitive market. They provide not just legal exclusivity but also embody the reputation and goodwill you build with customers.

Understanding what can be trademarked—virtually any distinctive sign, from names and logos to sounds and colors—and the process for registering and maintaining trademarks is crucial for brand owners. Each step matters: from clearance searches and registration filings to renewals and enforcement.

The legal framework for trademark protection in the United States is primarily established by the Trademark Act of 1946, commonly known as the Lanham Act. This legislation marked a significant milestone in the development of trademark law, providing federal protection for registered marks. Historically, the terms “trade mark” and “trade marks” have been used in legal contexts to refer to these protected signs, reflecting the evolution of trademark law.

Jurisdictional differences add complexity (trademarks are essentially national rights, and rules vary), but mechanisms like the Madrid System help secure multi-country protection. With the right strategy, businesses can ensure trademark protection wherever they operate or plan to expand.

Trademarks not only protect brand owners by fending off imitators—they also serve consumers by acting as shortcuts for trust and quality. Trademark-intensive industries are major contributors to the economy, accounting for millions of jobs and a significant GDP.

In a world where brand recognition can make or break a business, trademarks are more important than ever. They allow businesses—from the smallest startups to the largest multinationals—to build and defend a unique market presence. By understanding and leveraging trademark laws, companies can maintain a competitive edge and ensure their brand’s long-term success.

Remember: Your brand name or logo might be one of your company’s most valuable assets—treat it with the importance it deserves by securing and enforcing your trademarks with experienced legal counsel who understands your business goals.

About the Author:

Andrew Rapacke is the Managing Partner at Rapacke Law Group and a Registered Patent Attorney specializing in intellectual property protection for tech startups and innovative businesses. With extensive experience helping founders and entrepreneurs protect their brands, Andrew provides strategic trademark guidance that aligns legal protection with business growth objectives.

Connect with Andrew on LinkedIn or follow @rapackelaw on Twitter/X and @rapackelaw on Instagram for ongoing IP insights.

To Your Success,

Andrew Rapacke, Managing Partner, Registered Patent Attorney, Rapacke Law Group

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a trademark?

A trademark is a unique identifier for a brand—a property right in your brand identity, giving you exclusive rights to use that identifier in commerce for specified goods/services. Trademarks can be words, designs, slogans, and more—essential tools for protecting brand identity and consumer recognition in the marketplace.

Can I trademark a slogan?

Yes, you can trademark a slogan if it is distinctive and used to identify the source of your goods or services. The slogan should not be a common phrase describing the product. For example, Nike’s “Just Do It” is trademarked. Making sure your slogan is unique to your brand (and not used widely in everyday language) will strengthen your trademark application.

What is the difference between a trademark and a service mark?

The difference is simply the nature of what’s being offered: a trademark refers to marks for goods (physical products), whereas a service mark refers to marks for services. In practice, legal protections are identical. Both are registered through the same process. Trademark = product identifier, service mark = service identifier, but both fall under trademark law’s umbrella.

How long does a trademark last?

Potentially forever—as long as you keep using it and meet renewal requirements. In the United States, trademark registration initially lasts 10 years from the registration date. To maintain it, you must file a renewal (and proof of continued use) at the 10-year mark, with an additional check-in around 5-6 years. Each successful renewal adds another 10-year term with no limit to renewals. Many famous trademarks are over a century old and still going strong (Coca-Cola dates to the late 1800s).

What is the Madrid System?

The Madrid System is an international trademark filing treaty that makes it easier to seek trademark protection in multiple countries. Instead of filing separate applications in each country, you can file one international application through your home trademark office and designate over 100 countries where you want your mark protected. WIPO handles the centralized application, and each designated country’s trademark office examines the request under its laws. The Madrid System significantly reduces the complexity and cost of worldwide trademark registration, which benefits businesses expanding globally.