Your patent application has just been published. Within 48 hours, three competitors downloaded it, and their engineers are already designing around your claims. This scenario plays out daily across tech startups, yet most inventors don’t realize that their pending patent is broadcasting a roadmap for competitors to beat them faster and more cheaply. According to World Intellectual Property Organization 2023 data, only 36.2% of patents remain in force after a decade, and a mere 17.5% reach their full 20-year term. Yet those who navigate the process successfully see dramatic results: startups securing their first patent experience 55% more employment growth and 80% more sales growth over five years compared to similar companies without patents. Obtaining patents is a crucial step for protecting inventive ideas and securing a competitive advantage, as patents provide inventors with exclusive rights and incentives to innovate.

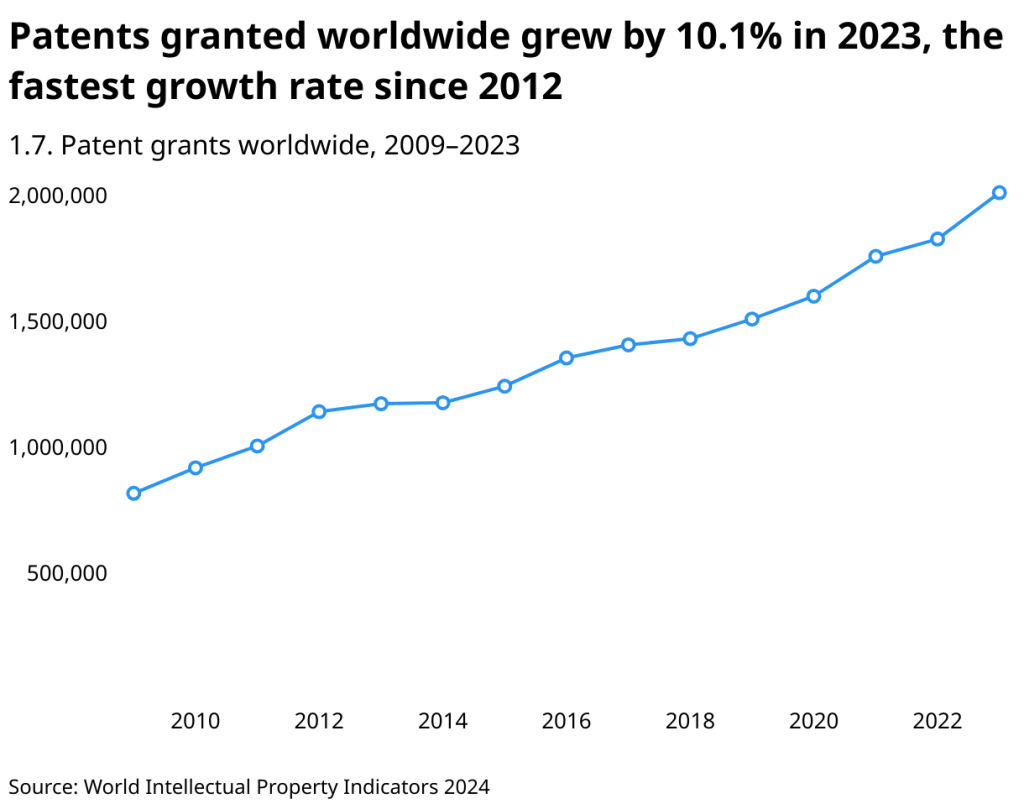

The gap between filing and grant isn’t just bureaucratic delay; it’s where most patent strategies succeed or fail. In 2023, innovators filed 3.55 million patent applications worldwide, reaching a new record high. The same year, approximately 2 million patents were granted globally, representing a 10.1% surge from the previous year and the fastest growth since 2012.

At the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office alone, approximately 63% of applications receive allowance on first examination, increasing to over 80% after subsequent rounds, including Requests for Continued Examination. During this process, patent applications are published, and published application details provide inventors with public notice and transparency, making information about inventive ideas accessible to the public. Each published application is tracked using a unique publication number, which helps identify and locate these documents.

Understanding the journey from application to grant determines whether your innovation becomes enforceable intellectual property or joins the majority of abandoned ideas. This guide walks you through the examination process, international filing strategies, enforcement mechanisms, and maintenance requirements, providing current data, expert insights, and real-world examples that focus on tech sectors, including software, SaaS, consumer electronics, AI, and manufacturing automation.

What Is a “Patent Granted”?

A granted patent represents official approval from a patent office confirming your invention meets all legal requirements, novelty, non-obviousness, and utility, thereby providing exclusive rights to your innovation. This transforms your application from a pending request into enforceable property rights, allowing you to prevent others from making, using, selling, offering to sell, or importing the patented invention without permission.

The distinction between “patent pending” and “patent granted” is fundamental. Patent pending status begins when you file, but it confers no enforceable legal rights; you cannot sue for infringement on a pending application. It establishes a priority date and deters copycats, but it serves as a temporary placeholder. Only after the patent office completes its examination. It confirms that your invention satisfies the patentability requirements; if granted, the patent becomes a powerful intellectual property asset with legal teeth.

In most jurisdictions, including the United States, a granted utility patent provides 20 years of exclusive rights from the date of filing. Design patents in the U.S. receive 15 years from the date of grant; plant patents receive 20 years from the date of filing. During this term, you effectively hold a limited monopoly on your invention.

The grant process involves a rigorous examination by patent examiners, who assess whether your invention represents a genuine advance over existing patents and prior art. In cutting-edge fields such as software and AI, examiners also evaluate patent eligibility. For instance, the USPTO issued updated guidance in 2023–2024, clarifying how AI-related inventions meet subject-matter eligibility requirements. A granted patent means your invention cleared all hurdles and is recognized as a unique, patentable contribution.

For software and SaaS innovators navigating these complex eligibility requirements, our comprehensive SaaS Patent Guide 2.0 breaks down exactly how to position your invention for USPTO approval.

Legal Rights and Protections of Granted Patents

When a patent is granted, the patent owner receives comprehensive exclusive rights providing significant commercial and legal advantages:

Exclusive Making, Using, and Selling: The primary right is authority to exclude others from making, using, selling, offering for sale, or importing the patented invention in the jurisdiction where the patent is granted. This temporary monopoly (20 years for utility patents from filing) enables premium pricing and market share capture without direct competition. A patented pharmaceutical drug or software algorithm can be sold without competitors legally producing the same solution.

Licensing Rights: As a patent holder, you can license the invention to others, generating revenue streams while retaining ownership of the invention. Licenses can be exclusive (giving rights to just one company) or non-exclusive (allowing multiple companies to use the technology), involving upfront payments, ongoing royalties, or cross-licensing agreements. Many tech companies leverage licensing, with holders of standard-essential patents in 5G technology licensing their patents to phone manufacturers for royalties.

Enforcement and Litigation: A granted patent provides legal standing to enforce rights through litigation. If an unauthorized party infringes, you can file patent infringement lawsuits in federal court seeking monetary damages and injunctive relief. Damages include lost profits or reasonable royalties, and courts can award up to treble (3×) damages for willful infringement. In 2024, U.S. patent cases resulted in $4.3 billion in total damages awarded, the highest annual sum in over a decade, with individual jury verdicts reaching hundreds of millions of dollars.

Retroactive Enforcement: After patent grant, you may pursue damages dating back to the publication date (typically 18 months after filing) if your application was published and issued claims are substantially identical to published claims. This means the clock for potential damages starts ticking at publication, extending the damages period once the patent issues.

Injunctive Power: The ability to seek injunctions stopping others from using the invention represents perhaps the most significant power. While U.S. courts made injunctive relief harder to obtain after eBay v. MercExchange (2006), patent owners can also approach the U.S. International Trade Commission (ITC) to block infringing imports. The ITC can issue exclusion orders, enforced by Customs, which prevent products infringing U.S. patents from entering the country—often more quickly and effectively than other measures against foreign manufacturers.

Damages and Legal Remedies: If you succeed in infringement litigation, courts award damages adequate to compensate for infringement—minimally a royalty, possibly lost profits if the infringer’s sales diverted your sales. For businesses developing innovative products, such as a SaaS MVP, egregious or willful infringement may result in enhanced damages of up to three times the proven amount under 35 U.S.C. § 284. The stakes are enormous: a 2024 jury verdict in Texas initially awarded $847 million on two patents before post-trial motions, while another case saw $525 million awarded to Kove against AWS.

Patent Examination and Grant Process

The journey from filing to grant involves multiple examination stages and interaction with the patent office, where a patent examiner reviews your application, assesses prior art, and determines patentability. Understanding this process helps maximize success chances, particularly when working with experienced patent counsel who know how to navigate examiner objections, craft persuasive responses, and position applications for first-action allowance rather than multiple costly Office Action rounds. During the examination process, a patent examiner is responsible for reviewing the application, assessing prior art, and determining whether the invention meets the requirements for patentability. Understanding this process helps maximize success chances—particularly when working with experienced patent counsel who know how to navigate examiner objections and craft persuasive responses.

Filing and Formal Examination

The process begins when you file a patent application (provisional, non-provisional, or international). The patent office conducts an initial formalities examination to ensure your application is complete and properly formatted. Examiners verify the presence of all required elements: a written specification (description), one or more claims that particularly point out the invention, necessary drawings, an abstract, and the required filing fees. Missing critical elements trigger notices requiring corrections—an incomplete application can lose its filing date.

Application Publishing

In most jurisdictions, patent applications are published 18 months after the earliest priority date (unless you opt out in the U.S. by not filing foreign applications). Publication makes your application publicly viewable but maintains “patent pending” status. Publication significance: After your patent grants, you can potentially obtain damages for infringement occurring post-publication. It also allows competitors to monitor what you’re seeking to patent.

Substantive Examination

After passing formalities, applications enter substantive examination. Patent examiners—typically technical specialists in the relevant field—review whether claimed inventions meet core patentability criteria: novelty (is it new?), non-obviousness (is it an inventive step over what was known?), and utility/industrial applicability (does it have a useful purpose?).

Examiners perform prior art searches, scouring patent databases, technical journals, and publications for relevant references. They utilize classification systems, such as the Cooperative Patent Classification, and keywords to identify prior patents and non-patent literature. For a drone navigation system, examiners search prior patents on drone guidance, GPS systems, obstacle avoidance algorithms, and related technologies.

Examiners also check adequate disclosure (sufficient detail?), clarity of claims, and patentable subject matter. In software or business methods, examiners scrutinize whether claims are directed to abstract ideas or include technical innovation—part of the subject-matter eligibility analysis.

In July 2024, the USPTO issued a Guidance Update on Patent Subject Matter Eligibility, including on Artificial Intelligence, along with AI-focused examples, to help examiners and applicants evaluate how AI-related inventions satisfy subject-matter eligibility requirements under 35 U.S.C. § 101.

For AI innovators facing these complex eligibility challenges, our AI Patent Mastery resource provides detailed strategies for crafting claims that satisfy both technical innovation requirements and patent eligibility standards.

Office Actions and Responses

The first substantive communication is typically an Office Action—an official letter detailing objections or rejections. Most applications receive initial rejections. Common issues include:

- Novelty rejections: Citing prior art showing each element of your claim.

- Obviousness rejections: Asserting your invention would be obvious to someone skilled in the art, given prior references.

- Clarity or formality objections: Ambiguous claim wording, improper drawings, and lack of support.

- Subject matter rejections: Claims not directed to patent-eligible subject matter.

- Insufficient disclosure: Description doesn’t enable making and using the invention.

Initial rejection is normal—not alarming. You typically have 3 months to respond (extendable to 6 months, subject to additional fees). Responses may include claim amendments (clarifying or narrowing over prior art) and arguments explaining why the examiner is wrong or why the invention is patentable.

This ping-pong can go through multiple iterations. Examiners may issue final Office Actions after at least two rounds if unconvinced. A “final” rejection doesn’t end the road—you can file a Request for Continued Examination (RCE) to reopen prosecution with new amendments, or appeal to the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB). Many applications, especially in complex fields, require two to three Office Action rounds before allowance is granted. Missing deadlines leads to abandonment (sometimes revivable with additional fees).

Examiner interviews—whether conducted by phone, video, or in-person meetings—often help clarify paths to allowance. Examiners may suggest acceptable claim wording, making interviews particularly valuable for complex cases. At Rapacke Law Group, we strategically use examiner interviews to accelerate allowances and strengthen claim scope—often resolving issues that might otherwise require multiple Office Action rounds, saving clients both time and prosecution costs

Allowance and Grant

If the examiner concludes your application meets all requirements, you receive a Notice of Allowance. This signals the examiner has decided to grant the patent. The notice lists allowed claims and requests payment of the issue fee. In the U.S., you have three months to make the payment. Upon payment, the patent office issues the patent.

An official grant occurs when the patent is published in the official gazette, accompanied by an assigned patent number. In the U.S., patents are issued weekly on Tuesdays with sequential numbers. The USPTO issued 324,000+ patents in 2024, meaning hundreds or thousands are granted each week.

You receive a patent certificate (physical and/or electronic) as proof. The granted patent is published in public databases with full details, including specification, claims, citations, and prosecution history. Your application is no longer confidentially pending; it has been issued as a patent, and anyone can review it. Critically, now you can enforce it.

Examination Timeline Expectations

Time from filing to grant varies widely. The average pendency typically spans 1 to 3 years, depending on the complexity and volume of the backlog. As of late 2024, USPTO’s average total pendency exceeded 20 months (approximately 1.7 years), with a substantial backlog of over 800,000 pending applications. Simpler mechanical inventions might clear in a year, whereas highly complex fields like AI or biotechnology often take longer, sometimes 3-5 years with appeals.

Illustrative timeline:

- Filing to First Office Action: ~12–18 months (current USPTO average ~18–20 months)

- Office Action Response Period: ~3–6 months (applicant time)

- Final Office Action: ~18–24 months (if issues persist)

- Notice of Allowance: ~24–36 months (for many applications)

- Patent Grant: ~27–39 months (after paying issue fee, typically 2–3 months post-allowance)

These timelines represent standard examination. For innovations requiring faster protection—such as when competitors enter your space or investors need patent security—experienced counsel can effectively leverage accelerated examination programs. At Rapacke Law Group, we guide clients through Track One prioritized examination and other acceleration options when timing is critical for business strategy.

Fast-Track Options: If time is critical, most patent offices offer accelerated examination. In the U.S., Track One prioritized examination dramatically reduces time, often to 6–12 months. In fiscal year 2023, the average time from the grant of a Track One petition to final disposition was 5.4 months, with the first Office Action issued approximately 1.9 months after the petition was granted. You could file and receive a patent grant within 9 months in the best cases—extremely useful for attracting investors or enforcing against infringers.

Another acceleration: Patent Prosecution Highway (PPH)—if one patent office (say, European Patent Office) allows your claims, you can request accelerated processing in another office (like USPTO) based on that favorable result. PPH significantly speeds examination in the second office.

Responding to Office Actions: Strategy and Execution

Responding to Office Actions determines whether applications ultimately succeed. When receiving an Office Action, carefully analyze examiner citations and arguments. The document lists prior art references and explains how they relate to your claims.

Strong response strategies:

Amendments to Claims: If the examiner’s prior art is close to your claims, amend the claims to distinguish your invention. Add technical features described initially but not included in claims—if those features aren’t in cited art. All amendments should be carefully considered—adding limitations overcomes prior art but narrows the scope of protection. Find the sweet spot: narrow enough to be novel and non-obvious, yet broad enough for commercial value.

Argumentation: Whether or not amending includes arguments related to technology patents. Argue that the examiner’s interpretation of prior art is incorrect, or the combination of references is improper (perhaps references are from very different fields, making the combination non-obvious). Back arguments with evidence or sound reasoning—cite technical details from prior art showing they don’t teach what the examiner thinks, or submit declarations with experimental data showing unexpected results (supporting non-obviousness).

Interview with Examiner: Request examiner interviews to facilitate direct case discussion. These informal exchanges provide insight into acceptable claim wording. Examiners often hint at allowable approaches. Following the interview, you have clearer plans for amendments that will lead to approval.

Timing and Extensions: Respond within 3 months to avoid abandonment, though you can buy extensions to 6 months (with increasing fees). Responding sooner keeps the process moving and demonstrates cooperation. Sometimes, strategically taking extra time makes sense if awaiting results from another patent office or gathering data.

Missing deadlines causes abandonment. Revival procedures exist (if delay was unintentional) but are costly and not guaranteed—so carefully docket deadlines, especially when navigating the AI patent application process.

After Final Office Actions

After receiving Final Office Actions, options include:

Request for Continued Examination (RCE): Very common—pay a fee essentially resetting prosecution, allowing new amendments and arguments. The case becomes “active” again, and the examiner issues another (non-final) Office Action. RCEs give continued examiner dialogue. Allowance rates have historically been high for those who persist; most ultimately allowed U.S. patents have gone through at least one RCE. The overall eventual grant rate at the USPTO (including RCEs and continuations) exceeds 80%, indicating that persistence often steers applications toward allowance.

Appeal to PTAB: If you believe your arguments are strong and the examiner is wrong, appeal to the Patent Trial and Appeal Board. Appeals involve writing legal briefs to argue examiner errors, which may also include oral hearings. Appeals can take several years, further adding to the delay. Often, applicants file appeals while also filing RCEs in parallel, thereby keeping prosecution ongoing and potentially leading examiners to reconsider rather than contest the appeals. For expert guidance with patent appeals, consider consulting with Andrew Rapacke, an experienced patent attorney.

After Final Consideration: Programs like the After Final Consideration Pilot (AFCP) allow limited amendments after final, trying to get allowance without RCE. Examiners consider after-final responses only if changes aren’t extensive and allowability is quickly determinable.

Responding to Office Actions is a negotiation where experienced patent attorneys bring substantial value—knowing how to navigate rules, frame persuasive arguments, and determine when to concede versus stand firm. At Rapacke Law Group, we handle Office Action responses under our transparent fixed-fee model, eliminating the uncertainty of hourly billing that can make prosecution costs unpredictable. Research indicates that collaborating with experienced patent professionals yields better outcomes, and each response builds a record (the ‘prosecution history’), which can be crucial if patents are litigated—statements made can be interpreted as claims later.

Notice of Allowance and Patent Grant

Receiving Notice of Allowance is a milestone—the examiner has determined your application is in condition for allowance, with all pending claims considered patentable.

What happens next:

Notice of Allowance: Official document stating your application has been allowed, listing allowed claims and informing you of issue fees (and publication fees if applicable). For U.S. utility patents, issue fees for large entities currently range from $1,200 to $1,500 (with discounts for small/micro entities). You generally have 3 months from the Notice of Allowance to pay. Failing to pay on time leads to abandonment, despite being allowed—obviously undesirable after such effort (though limited windows exist to petition for revival if payments are missed by mistake).

Issue Fee Payment: Once you pay the issue fee, the patent office schedules your patent for issuance. Between payment and actual grant, if serious errors are realized or there is reason to withdraw (e.g., new prior art has surfaced), options exist, such as filing continuation applications or petitions to withdraw from issue—exceptional cases. Typically, applicants await a grant.

Patent Number and Issuance: On the issuance date, the patent office publishes patent details and assigns a patent number. USPTO issues patents every Tuesday with sequentially assigned numbers. You can often find assigned patent numbers a week before issue dates via public databases or the USPTO’s Patent Center. Patent numbers are unique identifiers (e.g., US 11,000,000+) used to identify patents henceforth.

Patent Certificate: The patent office issues certificates (either electronic or paper copies, depending on the jurisdiction and preference). This certificate is essentially your title deed—formal proof of patent grant. The USPTO provides printed ribbon copies (nice for framing) unless you opt for electronic certificates only.

Publication and Public Record: Entire file histories (correspondence, applications, drawings, claims) typically become public upon grant (if not already public from earlier publication). Granted patent specifications are published—in the U.S., granted patents are published in full text on the USPTO website and databases like Google Patents on issuance day. Technical details of your invention are now part of the public domain knowledge (not rights). In exchange, you have legal rights. Published documents reveal final, legally enforceable claim sets, often citing prior art considered during examination on the front pages.

Patent Term: For utility patents, the term is generally 20 years from the earliest effective U.S. filing date (excluding provisional filings). Actual expiration dates can be affected by patent term adjustments (PTA) and extensions. PTA is standard—if patent offices cause undue examination delays (beyond specific timelines), extra days may be added to the terms. Notices of Allowance in the U.S. often include PTA calculations (e.g., “Patent Term Adjustment: 182 days”), which are added to the 20-year terms. Extensions are more specific (like pharmaceutical patents undergoing FDA regulatory delays). Patent terms are set at grant—diarize when they’ll expire.

After Grant – Marking and Notice: Once patents are granted, mark products with patent numbers (e.g., “U.S. Patent No. X, XXX, XXX”). Under U.S. law, you can only collect damages for infringement if infringers had notice—marking products with patent numbers gives constructive notice to the world. Modern virtual marking options exist (listing web pages associating products with patent numbers). Marking patented products is a best practice, as it maximizes the ability to recover damages later if someone infringes on the patent.

At the grant moment, inventions go from applications (essentially pending approval requests) to enforceable property rights. With patents in hand, you can license, sell, enforce, or simply enjoy peace of mind, having secured intellectual property.

Geographic Scope and Jurisdictional Considerations

Patent rights are territorial—patents are only valid in the countries or regions where they are granted. No “worldwide patent” exists. Inventors need strategies for which countries to seek protection in, balancing costs and potential benefits. When developing an international patent strategy, it’s essential to consider foreign patents to ensure the security of your intellectual property across multiple jurisdictions and to align with international patent systems.

USPTO (United States): Patents granted by USPTO provide rights within the United States and territories. They won’t stop competitors from making products in China or selling in Europe. If those are concerns, you need patents in those jurisdictions. Many U.S. inventors initially focus on U.S. patents (large market, familiar legal system), then consider expanding abroad.

Major International Patents: Other major players include the European Patent Office (EPO), which examines and grants patents validatable in multiple European countries (currently 39 member states), as well as national offices such as China’s CNIPA, Japan’s Patent Office (JPO), and Korea’s IP Office (KIPO). EPO patents aren’t single Europe-wide patents; once EPO grants, you “validate” in each country of interest (paying fees and fulfilling translation requirements), essentially turning into bundles of national patents subject to each country’s enforcement and maintenance rules.

Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT): For a global strategy, PCT is popular. The PCT is an international treaty with over 150 contracting states (as of 2025), allowing you to file one “international application” then later enter national phases in each country of interest (by 30 months from priority dates in most cases). PCT itself doesn’t grant patents, but streamlines the filing process and provides preliminary examinations and searches. Think of it as buying time and global placeholders—you can defer significant multi-country filing expenses for up to 2.5 years while gauging commercial viability in different markets.

Strategic Considerations for Geographic Coverage:

Market Size & Potential: Identify where your product or technology has significant markets. For automotive software inventions, target the U.S., Europe (EPO), China, Japan, and South Korea—all major hubs in the automotive industry. In 2023, Asia accounted for about 68.7% of global patent applications (and 69.7% of patent grants), underscoring Asia’s (especially China, Japan, and Korea) massive patent activity. Many companies ensure filings in China, not just for manufacturing, but because Chinese companies patent heavily. China issued over 920,797 patents in 2023, nearly triple the U.S. output.

Manufacturing Locations: Even if countries aren’t major consumer markets, obtain patents where competitors might manufacture infringing products. Many high-tech products are manufactured in China or Taiwan; having patents in those jurisdictions allows for stopping production at the source or negotiating licenses.

Competitor Presence: Where are the main competitors located or selling? If big competitors are based in Germany, German (or EPO) patents could be valuable for blocking them or leveraging cross-licenses. If competitors are emerging in India, consider Indian patents—notably, India granted 149% more patents in 2023 than in 2022, indicating that emerging markets are strengthening their IP regimes.

Costs and Budget: Filing and maintaining patents is expensive. Each country has its own fees, attorney costs, and translation costs (significant for languages like Japanese, Chinese, and Korean). Rough estimate: U.S. patents from start to grant might cost $10k–$20k in legal and office fees. European patents are similar, plus validation fees. Japan, China, and others are also in that ballpark or higher. Maintaining them over the years adds more costs. Small entities often choose 2-5 key countries. Larger companies might file in a broader range (20, 30+ countries, if inventions are core). Prioritize based on ROI—where will patents give the most protection or licensing opportunities for the money?

At Rapacke Law Group, we use transparent, fixed-fee pricing for patent applications—you know the total investment upfront, unlike traditional hourly billing, which can unpredictably increase during prosecution. This allows you to budget strategically for international filings and make informed decisions about geographic coverage.

Enforcement & Legal System: Consider the enforcement strength in countries. Patents in some jurisdictions are harder to enforce (due to slow courts or weak remedies). The U.S. and Germany are known for relatively effective patent enforcement (Germany offers quick injunctions, the U.S. offers big damages in some cases). China’s enforcement has improved with the establishment of specialized IP courts and significant damages awards, reflecting China’s push to foster innovation.

In practice, many tech startups initially file in the U.S. and then file a PCT to maintain options internationally. At 30-month PCT deadlines, they decide which countries to enter based on business plans or the interest of foreign partners. For tech and SaaS, key jurisdictions often include the U.S., EPO, China, and Japan/Korea. For consumer electronics, add China, Japan, Korea, maybe Taiwan (many electronics companies file there due to manufacturing). For AI and software, note that Europe has stricter software patent rules, while China and the U.S. grant lots of AI patents—China leads in AI patent volume with almost 13,000 AI-related patents granted in 2024 vs ~8,600 in the U.S. AI innovators might ensure filings in both the U.S. and China to cover key innovation centers.

Jurisdictional strategy maximizes coverage where it counts without wasting resources where patents won’t serve interests. It requires examining invention markets, manufacturing chains, and competitors globally. At Rapacke Law Group, we coordinate international filings through our network of trusted foreign associates, helping clients develop cost-effective global protection strategies using transparent, fixed-fee pricing for U.S. filings that allows strategic budgeting for international expansion.

Enforcement and Commercial Benefits

Granted, patents aren’t wall decorations—they’re pivotal business tools. Enforcing patents and leveraging them commercially is where the rubber meets the road in extracting value from inventions.

Market Exclusivity and Competitive Advantage

The most direct benefit is the exclusive market positioning that patents can grant. If patents cover features or products that consumers want, you can be the sole provider (legally) during the patent term. This market exclusivity allows charging higher prices (competitors can’t undercut with copycats) and building market share. For many companies, particularly those in the pharmaceutical and biotech industries, patents are a lifeblood, allowing for the recoupment of R&D investments—without patents, generic competitors would drive prices down rapidly.

In tech fields, advantages may be shorter-lived (technology moves quickly, and patents often cover specific implementations), but having patents on key technologies keeps competitors at bay. Studies show a correlation between patent protection and higher company valuations. Investors and acquirers often view patents as signs of defensible businesses. According to the USPTO and academic research, startups that secure patents tend to grow faster. After receiving the first patent grants, companies experienced 55% more employment growth and 80% more sales growth over five years compared to similar companies without patents. Additionally, utilizing patents as collateral can increase venture capital funding by an average of 76% over a three-year period. This is concrete evidence that patents translate into tangible business benefits, including easier fundraising, faster growth, and stronger competitive positions.

Licensing and Revenue Generation

If you don’t want to (or can’t) exclusively make and sell inventions yourself, license rights to others. Licensing can be highly lucrative and is a big part of many companies’ IP strategies. Small R&D companies might patent new semiconductor designs and then license them to big chip manufacturers for royalties on each unit produced. Many universities license patents arising from academic research to industry (technology transfer). License deals are structured in many ways—lump sum payments, running royalties (e.g., 5% of sales), milestone payments, or cross-licenses (where you and another company exchange rights to each other’s patents, which is useful if each has blocking patents that the other needs).

A notable example is IBM, which has historically earned large sums (well over a billion dollars annually in some years) from licensing its extensive patent portfolios. Cross-licensing is common in sectors such as smartphones, where companies like Samsung, Apple, and Nokia often have agreements that allow each other to use certain patented technologies, thereby avoiding constant litigation and ensuring freedom to operate. Well-managed patent portfolios can become revenue streams in their own right. Even if you do not produce products, you might find someone interested in your patented tech willing to pay for access. This can be a core business model for inventors and small entities—develop and patent technology, then license it to bigger players with manufacturing and distribution capabilities.

Attracting Investment and Partnerships

Patents serve as signals of innovation and bargaining chips in collaborations. Strong patent portfolios impress venture capitalists and corporate investors, suggesting that companies possess unique technology that is not easily copied. Government and academic perspectives often emphasize the importance of IP for economic growth—the USPTO reported that IP-intensive industries contribute over $7 trillion to the US GDP. If you’re a startup, having patents (or at least patent applications) significantly increases your chances of securing funding. European studies have found that start-ups with patents are up to 10 times more likely to secure early-stage funding compared to those without IP. Investors often ask, “Do you have a patent for this?” as the first question.

Patents also facilitate partnerships and joint ventures—larger companies might partner with startups if startups bring patented tech to the table (which bigger companies can utilize without fear). Patents can be used as collateral for loans (some banks and funds specialize in IP-backed lending).

Patent Portfolio Development – Offensive and Defensive

As businesses grow, they shift from thinking about one patent to managing entire portfolios. Portfolios can be used offensively (to sue others or license for revenue) and defensively (to deter lawsuits by others). Large tech companies often file hundreds or thousands of patents not only on core products but also on alternative implementations, improvements, and even things they don’t intend to use—partly to block competitors from getting those patents (defensive publishing strategy) and partly to have stacks of chips for courtroom poker games (if competitors sue you, counter-sue with your patents).

For example, Samsung in 2024 obtained 6,377 U.S. patents—more than any other company that year—reinforcing its positions in electronics, semiconductors, and other areas. IBM, known for massive patent troves, in recent years trimmed filings but focused on key areas like AI and quantum computing (still getting 2,465 U.S. patents in 2024, ranking top 10). IBM’s shift is strategic: rather than maximizing quantity, focus on patents aligning with future business. This illustrates that portfolios don’t need to be big to be strong—they need to be relevant. Targeted portfolios create patent thickets around products (making it hard for competitors to design around) and ensure you have leverage if confronted by others’ patents.

Patent Infringement and Legal Remedies

Identifying infringement involves comparing allegedly infringing products or processes to patent claims. Each claim is like a checklist of features—if a product has all the features of a claim, those claims are infringed. (Conversely, if even one element is missing, claims aren’t infringed—why claim drafting is critical.) Patent owners often conduct product analyses or hire experts to reverse-engineer devices to determine if they meet the claim limitations.

When identifying likely infringement, first consult patent counsel to verify that the patents are indeed being used and are enforceable (i.e., not expired or invalidated). Then you have routes:

Cease and Desist / Licensing Approach: Approach infringers with patent notifications and attempt to negotiate licenses. This is a softer approach, sometimes involving the maintenance of business relationships. However, be aware that in some jurisdictions (like the U.S.), once you accuse someone of infringement (even via letters), they might file declaratory judgment actions against you in courts of their choosing, seeking to invalidate patents or get non-infringement rulings. So communications need careful handling.

Litigation in Court: The primary avenues are suing in the appropriate courts. In the U.S., patent infringement cases are federal cases (filed in U.S. District Courts). There has been a concentration in certain courts known for their expertise in patent cases, such as the Eastern District of Texas or the District of Delaware. However, recent Supreme Court cases have somewhat curbed the practice of “forum shopping.” As of 2024, the Western District of Texas and the Eastern District of Texas were the most popular venues for patentees, with the Eastern District of Texas again being the top venue. Litigation can be expensive (ranging from $1 to $ 4 million through trials for complex cases) and lengthy (2-3 years is common for trials, although some “rocket docket” courts can complete trials faster).

If winning, remedies include:

- Damages: Compensating for past infringement. U.S. law sets damages as at least “reasonable royalties,” but if proving lost profits (lost sales because of infringement), you can get those. In addition to actual damages, if infringement was willful (i.e., the infringers were aware of the patents and still infringed egregiously), courts may award up to three times the damages as a penalty. In 2024, as mentioned, damages awards reached record levels, with over 90 patent cases resulting in damages, totaling a record $ 4.3 billion.

- Injunctive Relief: Courts can issue injunctions preventing future infringement. Post-eBay (2006), injunctions aren’t automatic even if winning—you must show irreparable harm, and money isn’t sufficient. Practicing entities (those selling products) have a better chance of obtaining injunctions than patent licensors under current case law. However, injunctions are still obtainable, especially if patents pertain to features driving sales or are challenging to design around.

- Attorneys’ Fees: In exceptional cases (like if infringers’ defenses were frivolous or they litigated in bad faith, or conversely if lawsuits were baseless), courts can order losing parties to pay winners’ attorney fees. Not routine, but a factor deterring completely meritless assertions or stubbornly unjustified defenses.

International Trade Commission (ITC) Proceedings: In the U.S., the ITC is a popular venue for patent owners, particularly when accused products are imported (which is often the case nowadays). ITC can investigate under Section 337 of the Tariff Act. ITC cases tend to move quickly—usually within 12-18 months—and if infringement is found, the ITC can issue exclusion orders (essentially import bans on infringing goods). U.S. Customs and Border Protection enforces exclusion orders. ITC can also issue cease-and-desist orders stopping domestic stockpiling or sales of already imported goods. ITC cannot award money damages, only injunctive relief (but potent relief). Another twist: ITC requires showing complainants have domestic industries related to patents (preventing purely foreign patent owners with no U.S. presence from using it arbitrarily).

Given all this, many companies prefer settling disputes via licensing rather than protracted court fights. Patent litigation is often a high-stakes poker game ending in negotiated licenses or cross-licenses. However, mere facts that could be litigated and potentially shut down someone’s products give leverage to achieve settlements.

Maintaining Your Granted Patent

Securing patents is a significant achievement, but owning patents is an ongoing responsibility. Patents require maintenance to remain in force and strategic management to ensure continued value delivery throughout their lives. If maintenance fees are not paid, the patent will expire, and the invention will enter the public domain, making it freely available for anyone to use or build upon.

Maintenance Fees (Annuities)

Most patent offices require periodic fees after a patent is granted to keep it alive. In the United States, these are maintenance fees due 3.5, 7.5, and 11.5 years after grant dates (with 6-month grace periods each time, albeit with late surcharges). These fees increase at each stage. According to the latest fee schedule, for large entities (e.g., large companies), USPTO maintenance fees are as follows: $2,000 at 3.5 years, $3,760 at 7.5 years, and $7,700 at 11.5 years. Small entities (companies with < 500 employees, independent inventors, nonprofits) pay 40% of hefty entity fees, and micro entities (very small businesses or individual inventors meeting certain income and application criteria) pay only 20%. The Unleashing American Innovators Act enhanced those discounts in 2022, with small entities receiving a 60% discount (up from 50%) and micro entities an 80% discount (up from 75%). The rationale is to ease the burdens on small patent owners, allowing them to afford to maintain their patents.

If maintenance fee deadlines are not met, patents will expire (lapse) as of the due dates. There’s a 6-month grace period during which you can still pay (with late fees) and not lose your rights, but after that, the patent goes abandoned. Safety valve exists: if patents unintentionally expire (e.g., genuinely missed by accident), you can petition for reinstatement by paying fees and showing lapses were unintentional—but this isn’t something to rely on; it can be costly and not guaranteed. Many companies use docketing software or services to track maintenance fee deadlines globally.

Why have maintenance fees at all? One reason is to encourage inventions that are not economically viable to be released into the public domain, rather than owners holding them for the full term without use. It’s a way to “weed out” patents that owners don’t value enough to pay for. Indeed, many patents are allowed to lapse. According to WIPO statistics, approximately 36% of patents remain in force 10 years after filing, and only 17.5% reach their full 20-year term. In other words, the majority of patents expire early because owners decide not to pay further fees (often due to lack of commercial relevance or financial constraints).

Monitoring and Enforcement

Maintenance isn’t just about paying fees—it also involves monitoring markets for potential infringements. Keep an eye on competitors and new products in technology spaces. Some companies establish internal IP watch teams or utilize external services to notify them if, for example, competitors release products that potentially utilize their patented technologies. Also monitor published patent applications and grants of competitors. Suppose someone is seeking patents very similar to yours. In that case, you might intervene (by submitting prior art for examiners to consider via pre-issuance submissions, or opposing in certain jurisdictions after grant).

Portfolio Management

If you have multiple patents, periodically conduct portfolio reviews. Large companies do this annually, examining each patent family to determine whether it remains useful. Should we abandon some to save costs? Should we sell or license out some we’re not using, but others might value? Should we file continuation applications to broaden or update some patents? Portfolio management aligns patents with current business strategies. For example, if companies pivoted from manufacturing hardware to focusing on SaaS software, hardware patents you no longer make might be candidates to license out or let lapse. In contrast, you might invest in more patent filings on the software side.

Key Maintenance Activities

Fee Tracking and Payment (Every due date): Ensure fees are paid on time. Set reminders well in advance.

Patent Portfolio Audit (Annually): Review lists of patents, remaining lives, and relations to products. Identify patents to keep, abandon, license, or sell. Evaluate if any filings (continuations, divisionals) should be made while still possible.

Competitive Monitoring (Continuously or quarterly): Watch competitors’ products and patent filings. Are they citing your patents in their applications (clues they’re aware of your IP)? Are they releasing something very similar to your claims (potential infringement)?

Legal Environment Check (Annually or with significant legal changes): Stay updated on patent law changes (e.g., new court rulings on patent subject matter, damages) potentially affecting values or enforceability of patents. Adjust strategies if needed.

Documentation and Record Keeping (Ongoing): Keep assignment records up to date (if company names change or you transfer patents, record at patent offices). Keep lab notebooks or technical documentation, which may be helpful in future enforcement.

Maintaining patents can be summarized as “Use it or lose it”—use them, either by practicing inventions, licensing, or at least keeping as strategic assets, and be willing to spend money maintaining if providing (or could provide) value. If not, it’s okay to let go; the public will benefit sooner in those cases.

How to Verify Patent Grant Status

Staying informed about patent status throughout the prosecution process and after grant requires familiarity with various patent databases and monitoring tools. These resources provide real-time information about patent applications, granted patents, and prosecution history.

USPTO Patent Center / PAIR: The United States Patent and Trademark Office provides an online system called Patent Center (replacing the older PAIR system for most uses). By entering application numbers or patent numbers, you can see the application or patent status. For pending applications, you can see if they are in examination, if Office Actions have been mailed, if allowed, etc. For granted patents, you can see if maintenance fees have been paid, if any post-grant proceedings (like reexams or IPRs) are ongoing, and if patents are still active. PAIR essentially shows file wrappers—every document in the prosecution history. Extremely useful if wanting to review how patents were obtained (say, looking at competitors’ patents, wanting to see what arguments they made to get allowed). Patent Center is available to the public for published applications and issued patents (you don’t even need an account for basic searches).

USPTO Patent Public Search: USPTO also launched a new Patent Public Search tool (web-based search interface) for searching patent literature. While primarily used for searching prior art, it also helps verify the details of granted patents. You can search by patent numbers, inventors, assignees, keywords, etc., and find out if patents exist.

Global Dossier: Convenient feature for those with applications in multiple jurisdictions. Global Dossier (accessible through USPTO or EPO websites) lets you see families of patent applications across different countries and examination documents from each. For instance, if filing applications via the PCT and entering the U.S., Europe, and China, Global Dossier can display status and documents from the USPTO, EPO, and CNIPA in one place. Great way to monitor corresponding applications.

WIPO PATENTSCOPE and EPO Espacenet: These are international databases. PATENTSCOPE (WIPO) is an excellent resource for searching PCT applications and also features national collections. To verify if someone has filed PCT (international) applications, you can search by name or keywords. Espacenet (by the European Patent Office) is another free search tool with global coverage of patents, often used to quickly retrieve patent PDFs or view simple legal status (via the INPADOC legal status feature).

National Registers: Each country often has online registers for patents. For example, EPO’s European Patent Register can show the status of European applications/patents (and if European patents were granted, whether validated in countries, whether any oppositions were filed). Japan has J-PlatPat (with an English interface), where you can check the status of Japanese patents.

Assignment and Ownership Records: In the U.S., you can search the USPTO Assignment Database to see who the recorded owners of patents or applications are. Keeping your own assignments recorded is vital to verify ownership (especially if needing to enforce, courts will check if you have a clear title). For others’ patents, assignment searches might reveal if patents were sold or transferred.

Regular status checking is crucial during examination phases when Office Actions and deadlines require prompt attention. Patent applicants should monitor applications monthly during active prosecution and quarterly for granted patents, ensuring awareness of maintenance requirements or potential issues.

Your Next Steps to Patent Grant Success

Understanding the journey from application to granted patent is one thing—executing a winning strategy that actually delivers enforceable IP protection is another. The statistics are clear: startups with patents grow 55% faster in employment and 80% faster in sales compared to those without IP protection. But only 36% of patents remain in force after a decade, and the gap between filing and grant is where most patent strategies either succeed or fail.

The bottom line is that weak patent applications drain resources, invite challenges, and deliver minimal competitive advantage—in fact, they help competitors more than they protect you by giving them a roadmap of your technology while providing little defensive value. Strong, strategically drafted patents deter competition, command respect in licensing negotiations, attract investor confidence, and create enforceable barriers around your innovation.

But here’s what most inventors and founders miss: the patent grant process isn’t just about getting a patent—it’s about securing the proper patent with claims that cover what matters commercially. Poor claim drafting costs market share. Missed prior art references waste time and money. Inadequate responses to Office Actions can unnecessarily narrow your protection. In the fields of AI and software, where patent eligibility challenges are intense, a single misstep can result in rejection. You’re not just competing against prior art—you’re racing competitors to market, fighting for investor attention, and building defensible technology moats. Every month of delay, every rejected claim, every missed deadline puts your competitive position at risk.

Take these immediate actions to secure your patent grant strategically:

- Schedule a Free IP Strategy Call with our team to evaluate your invention’s patentability, develop a targeted prosecution strategy, and identify potential Office Action challenges before filing—ensuring your application is positioned for the fastest, strongest possible grant.

- Review our AI Patent Mastery resource if your innovation involves artificial intelligence, machine learning, or algorithmic processes—understanding how to navigate Section 101 eligibility requirements is critical for AI patent success.

- Download our SaaS Patent Guide 2.0 for software and SaaS innovations—it provides specific strategies for claiming software inventions in ways that satisfy USPTO requirements and deliver commercial protection.

- Conduct a comprehensive prior art search before filing to identify potential rejection grounds early, allowing you to craft claims that distinguish your invention clearly from existing patents and avoid costly Office Action rounds.

- Develop a geographic filing strategy that aligns with your business plan by scheduling a strategy call to determine upfront whether PCT filing, direct national filings, or U.S.-only protection makes sense for your technology, market, and budget.

Your patent grant is the foundation of your IP strategy—whether you’re raising venture capital, licensing technology, deterring competitors, or building toward acquisition. Proper preparation during the application and examination phases determines whether you emerge with enforceable protection that drives business value or a weak patent that competitors can easily design around. The investment you make in strategic patent prosecution pays dividends for decades through market exclusivity, licensing revenue, and competitive positioning.

At Rapacke Law Group, we specialize in securing granted patents for tech innovators, SaaS companies, and AI pioneers. Our transparent, fixed-fee pricing eliminates the uncertainty of hourly billing, and our tech IP expertise ensures your application is strategically positioned from day one. Unlike traditional firms that bill by the hour and drag out prosecution, we’re incentivized to secure your grant efficiently while maximizing claim strength.

We’re so confident in our patent prosecution approach that we offer a straightforward guarantee:

- FREE strategy call with our patent team to evaluate your invention and develop a filing strategy.

- Experienced U.S. patent attorneys lead your application from start to finish—no paralegals handling critical prosecution work.

- One transparent flat-fee covering your entire patent application process (including Office Action responses).

- Full refund if USPTO denies your patent application*.

- Full refund or additional patent search if your invention has patentability issues (your choice)*.

Don’t let your innovation join the 64% of patents that fail before the 10-year mark. The window for establishing patent priority closes quickly—especially under the first-to-file system, where delays can cost you rights if competitors file first. Schedule your free IP strategy call now to secure your competitive advantage before competitors enter your space.

About the Author

Andrew Rapacke is Managing Partner and a Registered Patent Attorney at Rapacke Law Group, where he specializes in securing patent protection for tech innovators, SaaS companies, and AI pioneers. With extensive experience navigating complex USPTO examination procedures and crafting strategically valuable patent portfolios, Andrew helps founders and inventors transform innovations into enforceable intellectual property assets that drive business growth.

Connect with Andrew on LinkedIn or follow @rapackelaw on Twitter/X and @rapackelaw on Instagram.

To Your Success,

Andrew Rapacke

Managing Partner, Registered Patent Attorney

Rapacke Law Group