Your competitors are reading your software’s source code right now, or they would be, if you hadn’t protected it with the proper licensing strategy. When Adobe transitioned from perpetual licenses to Creative Cloud subscriptions in 2013, its subscription revenue exploded from approximately $1.2 billion in annualized recurring revenue to $18.3 billion in annual subscription revenue by 2023: a fifteenfold increase driven almost entirely by licensing strategy. Yet 37% of PC software globally remains unlicensed, representing $46.3 billion in lost revenue according to BSA’s Global Software Survey.

The gap between effective and ineffective licensing isn’t just about preventing piracy: it’s about aligning legal protection with business models, integrating patent portfolios with license terms, and understanding how enforcement mechanisms shape customer behavior. This guide explains how proprietary software licenses work, how to structure them for maximum protection, and what both vendors and users need to know to avoid costly mistakes.

Key Takeaways

Closed-Source Control: A proprietary software license is a legally binding contract that controls how users can install, use, and share closed-source software. Unlike open-source licenses that grant broad freedoms, proprietary licenses restrict access to source code and limit what users can do with software they purchase or subscribe to. When you obtain proprietary software, you acquire a non-exclusive right to use it under specific conditions; you do not own the underlying code or IP. As Micron’s EULA explicitly states, “no ownership is transferred to the user.”

Proprietary software provides critical competitive advantages for SaaS founders: dedicated vendor support, enhanced security through controlled access, and the ability to monetize innovations through carefully structured license terms. However, licensing alone isn’t enough; you need layered IP protection combining licenses with patents and trade secrets.

Monetization and Compliance: Proprietary licensing is essential for monetization, compliance, and long-term control over commercial software. High rates of unlicensed software use create both revenue loss and security risks: organizations face a 1-in-3 chance of malware from unlicensed software, with each infection costing approximately $2.4 million and taking 50 days to resolve on average. Robust licenses, combined with activation technology and patent protection, have helped reduce piracy rates, with Adobe’s cloud licensing significantly reducing casual copying and converting pirates into paying customers. But remember: licenses control user behavior, while patents prevent competitors from copying your core innovations.

Layered IP Protection: Beyond copyright protection, companies should actively secure patents for critical algorithms, user-interface workflows, and technical implementations. Patents provide broad protection of novel functionality and deter competitors from copying innovations. Google’s early dominance in search was bolstered by its PageRank algorithm patent, which gave it exclusive rights to that ranking method, demonstrating how patents provide the competitive moat that licenses alone cannot. In 2023, roughly 63% of all new utility patent applications in the U.S. were software-related, and startups with patents are over 6× more likely to secure venture funding.

EULA Terms Matter: The End User License Agreement defines usage limits, permitted devices/users, and prohibitions on reverse engineering, redistribution, and other activities. Understanding these terms is crucial for both vendors and customers. Many standard EULAs explicitly prohibit reverse engineering or modifying software; Oracle’s license even bans disclosing software benchmark results without consent. Vendors often reserve audit rights to verify compliance.

Modern Licensing Models: Proprietary software licenses come in various forms (perpetual, subscription, named user, floating, device-tied, feature-tiered), each supporting different business models and use cases. The software industry has shifted heavily toward subscriptions: Adobe’s revenue quintupled after switching from perpetual licenses to subscriptions because recurring revenue provides steadier cash flow and ensures users stay on the latest version.

What Is a Proprietary Software License?

A proprietary software license is a legal agreement that permits the use of computer software under strict terms while keeping the source code closed and inaccessible to users. Proprietary software is typically distributed under specific licensing agreements that govern its use, distribution, and modification, a core aspect of the proprietary software model. It serves as a permission contract between the software owner (developer or publisher) and the end user, establishing clear boundaries for permitted and prohibited activities.

Ownership remains with the vendor. Proprietary software is owned by a specific company or organization and is distributed under licensing terms that restrict users’ rights to modify, distribute, or access its underlying source code. When you purchase or subscribe to proprietary software, you obtain a license to use it under certain conditions; you do not own the software code itself. All rights, title, and intellectual property remain with the developer. Standard license clauses make this explicit: “All patent, copyright, trademark, and proprietary rights shall at all times remain with the vendor; no ownership interest is transferred.”

In modern practice, proprietary licensing works hand in hand with broader intellectual property strategy, and understanding this integration is critical for SaaS founders. Software companies don’t rely on EULAs alone: they also register copyrights (which arise automatically for code), trademarks (for brand names/logos), and file patents for novel software features or core algorithms. The license agreement governs user behavior and monetization, while copyrights and patents provide legal grounds to prevent unauthorized copying or competitive infringement. For venture-backed startups, this layered approach directly impacts valuation and fundability.

Users receive limited rights. These rights typically include installing and running the software for specific purposes (personal or business use) and making backup copies. Crucially, you cannot access the source code, modify the software, or redistribute it unless the license explicitly grants such rights. The software is provided either as compiled object code or as a service, with its internal workings kept confidential as trade secrets, one of three critical IP protection layers that work together with licensing and patents to create comprehensive protection for SaaS companies. Proprietary software is often called closed-source software because the source code is kept confidential and proprietary to the company that created it.

Source code is closed. Unlike open-source or free software under licenses such as the GNU GPL or MIT, which make the source code openly available, proprietary licenses keep the software’s source code closed-source. This protects the vendor’s innovations and prevents users from creating derivative works without permission. The development and maintenance of proprietary software are solely controlled by software companies, giving them complete authority over its features, updates, and distribution.

Proprietary licenses dominate commercially available software products. Most mainstream software runs on proprietary operating systems: Microsoft Windows and Apple macOS are closed-source and governed by strict EULAs. Apple’s macOS license explicitly prohibits installing the OS on non-Apple hardware, making “Hackintosh” setups a breach of the license. Other examples include Adobe Photoshop, Oracle Database, AutoCAD, and Salesforce CRM. Proprietary software vendors, such as Microsoft and Apple, require users to accept distribution restrictions and proprietary terms as part of the license agreement.

Proprietary desktop operating systems hold significant market share: in 2023, Windows accounted for approximately 71-74% of the global desktop OS market, and macOS approximately 15-16%, according to StatCounter Global Stats. That ubiquity underscores how most consumer software runs under proprietary licenses. This proprietary software model is contrasted with open-source models promoted by organizations like the Free Software Foundation, which advocate for user freedoms and open access to source code.

Software developers at proprietary software companies are responsible for development, maintenance, and support, and proprietary software is subject to restrictions not found in open-source alternatives.

Historical Context and Legal Foundations

The proprietary software licensing model evolved significantly from computing’s early days, when software was often bundled “free” with hardware and not treated as a separate product.

1969: IBM “unbundles” software: IBM’s decision in 1969 to start selling software separately from hardware was pivotal. Previously, buying an IBM mainframe included all software that came with it, with no separate license fees. Under pressure from an antitrust case, IBM changed course and began charging for software apart from machines. This created the independent software industry: companies could now develop software as a product with its own price and license. Historically, this software was often installed as software bundled with hardware, but the shift to separate licensing introduced new legal issues and clarified the legal status of software products.

Software gains copyright protection: The landmark Apple Computer, Inc. v. Franklin Computer Corp. (1983) case established that software, including machine-readable object code or burned into ROM chips, is protected by U.S. copyright law. This case established the application of copyright laws to software, confirming its legal status as intellectual property. This was the first appellate decision to explicitly recognize that an operating system or object code is a protectable literary work. That ruling gave legal teeth to proprietary licenses: if someone violates the license by copying or distributing code without permission, the software owner can sue for copyright infringement.

Rise of commercial software licensing (1970s–1990s): Once unbundled, software licensing took off. Companies like Microsoft, Oracle, and Adobe built massive businesses in the late 1970s through the 1990s by selling software licenses. They formalized shrink-wrap and click-wrap EULAs, started using product keys and activation to enforce them, and lobbied for stronger IP laws.

2000s: SaaS and new license models: The 2000s brought Internet distribution and Software-as-a-Service. Proprietary licenses evolved to cover cloud-based access and subscription models. Terms for uptime, data protection, and service availability began to appear. Vendors began including data privacy clauses that comply with laws such as the European Union’s GDPR (2018).

2010s: Open source challenges and hybrid models: While open source gained tremendous traction (as of 2024, an estimated 96% of applications contain some open-source code, with open components making up roughly 77% of the average codebase), proprietary software didn’t disappear. Instead, many companies adopted hybrid approaches, offering a core open-source project while selling proprietary add-ons or cloud services.

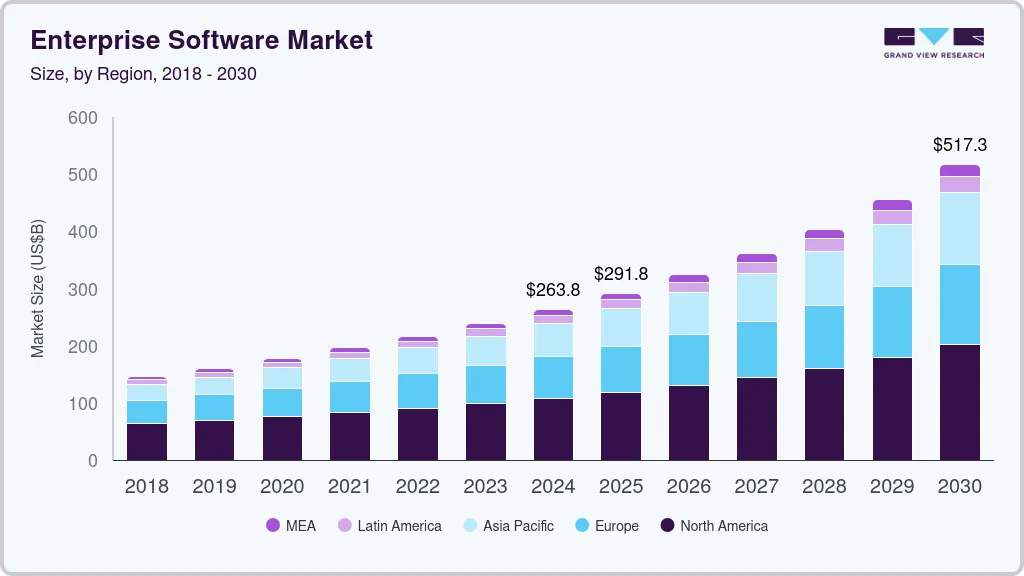

By the 2020s, the proprietary model will remain the foundation of the commercial software industry. The global enterprise software market was valued at approximately $264 billion in 2024, primarily driven by proprietary licensing.

The legal framework provided by a proprietary license enables software creators to enforce their rights and monetize their products. Modern EULAs are the product of 50+ years of legal and business developments: from IBM’s unbundling to court decisions cementing software IP rights to the advent of SaaS and international data laws. Understanding the legal status of software is crucial to avoiding legal issues related to unlicensed or abandoned software.

Core Elements of a Proprietary Software License Agreement

Every proprietary EULA contains standard components that define rights and restrictions. Proprietary software licenses often include limitations, such as distribution restrictions, that govern how the software can be used, copied, modified, or redistributed. These various restrictions are a defining feature of proprietary software licenses.

Grant of License

This section defines the fundamental scope of usage rights:

Permitted User/Entity: The license specifies if it’s granted to an individual, a company, or a specific number of users. A personal license may be limited to a single named individual; an enterprise license may allow use by the company’s employees. For organizations that require multiple installations, volume licenses are available, offering cost-effectiveness and centralized management.

Scope of Use: This clarifies permitted purposes, including personal, non-commercial use; business use; academic use; and related uses. Apple’s macOS license grants an individual user the right to install one copy on each Mac they own for personal use. For business use, it allows one copy per employee on their Macs.

Duration: Is it a perpetual license (you can use the version you bought) or a term license (a 1-year subscription after which rights expire unless renewed)? Many EULAs for purchased software are perpetual for that version with optional support periods, whereas SaaS agreements are typically term-based.

Ownership and Intellectual Property

Proprietary licenses explicitly state that all rights, title, and interest in the software and related materials remain with the vendor. A typical clause: “The Software is copyrighted and proprietary to ABC Corp. ABC retains all ownership and intellectual property rights in and to the Software and any copies. The licensee is not acquiring any ownership interest.”

This section may also reserve rights not expressly granted: “All rights not explicitly granted to you are reserved by the vendor.”

Restrictions on Use

EULAs typically contain a list of prohibited actions crucial to protect the vendor’s IP and business model:

Reverse engineering: You may not analyze the software to determine its source code or design (unless legally permitted for interoperability).

Decompilation: You may not convert compiled code back into human-readable form.

Modification: You may not alter, adapt, or create derivative works based on the software.

Resale or rental: You may not sell, rent, or lease your copy or license rights to anyone else.

Hosting for others: You may not use the software to provide services to third parties (e.g., in a data center for clients) without permission.

Some proprietary software licenses permit users to make copies of the software only for backup or archival purposes. Any other copying or distribution, except for backup or archival purposes, is strictly prohibited.

Oracle’s standard license prohibits “(i) making the Programs available to any third party, (ii) reverse engineering, disassembly or decompilation, and (iii) disclosing results of any benchmark tests without Oracle’s prior consent.” These EULA restrictions govern licensee behavior, but note that they cannot prevent a competitor from independently developing similar functionality. That’s where patents become essential for SaaS companies.

Installation and Usage Limits

Proprietary licenses often impose technical limits on how software can be installed or used. Proprietary software is frequently distributed as installed software, either pre-installed on hardware or as licensed installations, with strict controls on the number of permitted installations:

Device or Seat Limits: The EULA may specify that you may install or use the software on X number of devices or by Y number of users. For example, “one license = one installation on one computer” or a named-user license means only that the named person can use it.

Concurrent Use: If it’s a floating or network license, it may allow, say, 10 simultaneous users out of 100 in a company. License servers or online checks enforce this by denying the 11th user access until someone else logs out.

Virtualization or VM restrictions: Licenses increasingly address whether you can run software on virtual machines or in the cloud. Some licenses count each VM or cloud instance as a separate installation.

Geographic limits: The license might be valid only in certain countries or regions.

Audit Rights: To enforce these limits, vendors often reserve the right to audit customer usage: “Vendor may, upon X days’ notice, audit your books and systems to verify compliance with license limits.” A Flexera study found that 56% of enterprises surveyed in 2022 had been audited in the past year.

Updates, Maintenance, and Support

Software licenses address whether purchasing the license includes updates or support, or if those are separate:

Updates/Patches: Some perpetual licenses include one year of free updates (minor version updates or security patches). Subscription licenses inherently include updates as long as you subscribe: Microsoft 365 and Adobe Creative Cloud constantly deliver new features and security fixes to subscribers. However, once the vendor no longer supports a proprietary software product, users may face security risks and lack updates, making continued use problematic.

Maintenance Terms: If the license fee includes maintenance, the terms specify service levels.

Technical Support: EULAs or accompanying Support Agreements outline what support the user gets. Enterprise licenses often include an addendum that outlines email/phone support during business hours.

Termination

Proprietary licenses always include terms on how the license can end:

Termination for Breach: If the user materially breaches the license (e.g., by using it beyond the scope of the license or pirating it), the vendor may terminate the license upon notice. After termination, you must cease using the software and uninstall or destroy all copies.

Termination of Subscription: A subscription ends when you stop paying or at the end of the term if not renewed.

Effect of Termination: The license clarifies the consequences of termination. Typically: “Upon termination, you must immediately cease all use of the Software and delete or return all copies.”

Surviving Clauses: Certain provisions survive termination, including confidentiality, liability limits, and, in some cases, audit rights.

The termination clause reminds users that the license is conditional. Vendors use it as leverage to enforce terms. In cases of software piracy or unauthorized distribution, the vendor can terminate licenses and then pursue legal remedies.

Types of Proprietary Software Licenses

Proprietary licenses come in several standard structures tailored to different pricing and deployment strategies. For SaaS founders, choosing the right licensing model isn’t just about revenue; it affects how you protect IP, how investors value your company, and how you scale. Each license type offers distinct advantages and disadvantages, including differences in cost, flexibility, and support.

A perpetual license typically involves a one-time payment, granting the user indefinite use of the software without recurring fees. In contrast, subscription-based licenses require ongoing payments for continued access.

Proprietary software often includes licensing fees, subscription models, or additional charges for advanced features and support.

Perpetual License

A perpetual license is typically acquired through a one-time payment, allowing the customer to use a specific version of the software indefinitely. This was the traditional model for desktop and on-premise software for decades.

Example: Microsoft Office 2016 was sold for a one-time fee; users could use it indefinitely. However, they wouldn’t receive new features or major upgrades unless they purchased a new version later.

Support limitations: A perpetual license typically includes a limited period of support/updates (e.g., 1 year of patches). After that, you can still use the software, but the vendor may not provide fixes or support unless you purchase an extended support contract.

Upsides/Downsides: For customers, perpetual licenses can be cost-effective over the long term if you don’t need frequent upgrades, but they carry high upfront costs and the risk of running outdated software. For vendors, perpetual sales generate immediate revenue but can lead to “lumpy” cash flow.

Subscription (Term) License

A subscription license grants access to the software for a fixed term (monthly, yearly, or multi-year), typically tied to recurring payments. If you stop paying, your right to use the software ends. Subscription models often provide access to additional features and continuous updates as part of the service package.

Examples: Microsoft 365 is sold as a monthly/yearly subscription: if you cancel, Office eventually goes into read-only mode. Adobe Creative Cloud switched entirely to a subscription model in 2013: users pay monthly to access Photoshop, Illustrator, and related applications, and receive continuous updates.

Benefits: For vendors, subscriptions provide steady, predictable revenue and higher lifetime value when customers remain engaged. It also nearly eliminates piracy for cloud-based software. After moving to subscriptions, Adobe’s annual revenue skyrocketed from approximately $4 billion in 2011 to $21.5 billion in 2024, with 95% of Adobe’s revenue coming from subscriptions as of 2024.

For users, subscriptions mean lower upfront costs and always having the latest version, but over the long term, software can cost more.

The software industry has overwhelmingly embraced subscriptions. In 2023, Microsoft reported over 345 million paid Microsoft 365 seats globally: a testament to how even traditional software has moved to subscription at scale.

Named User (Per-User) License

A named user license allows one specific individual (the “named user”) to use the software, typically on multiple devices if needed, but only by that person. The license follows the person, not the machine.

Common: Enterprise applications such as CRM and ERP often use named-user licensing. For instance, a Salesforce CRM license is sold per named user: if a company has 50 sales reps, it buys 50 user licenses.

Enforcement: Usually enforced by account logins or license keys tied to a user ID.

Many cloud services (Microsoft 365, Adobe Creative Cloud) are effectively named-user: you sign in with your personal account, which is tied to a subscription. As of the end of 2023, Creative Cloud had over 33 million paid subscribers.

Floating (Concurrent) License

A floating license (or concurrent license) allows a set number of users to access the software simultaneously, but the identities of those users can vary. It’s like a pool of licenses shared among a larger group.

How it works: Say you have 100 potential users of software in your company, but at most 20 use it concurrently. Instead of buying 100 licenses, you buy 20 floating licenses. A license server manages these; up to 20 people can launch the software simultaneously. If a 21st tries, they’re blocked until someone exits.

Where used: Often in engineering, CAD, and high-end applications (MATLAB, AutoCAD, simulation tools). Companies can save significantly with floating licenses, with studies showing a 15-30% reduction in licenses.

Administration: Requires a license manager system to track usage. Vendors provide license server software that enforces concurrency limits and provides usage reports.

Device-Based (Per Machine) License

A device-based license ties usage to a specific computer or hardware unit. Only that machine can run the software.

Examples: Industrial and embedded software often uses device licenses. High-end creative or audio software sometimes comes with a USB dongle (hardware key) that must be plugged into the computer to run the software. Windows OEM licenses are tied to the device.

Dongles and hardware keys: These are physical USB or card keys that carry a license. The software requires the dongle to run. This is common for offline scenarios or to prevent copying.

Feature-Based or Tiered Licenses

In this model, a software product has multiple editions or modules, and the license you purchase determines which features, capacity, and additional capabilities you can use.

Editions (Tiered): Software is often sold as Standard, Professional, and Enterprise. Each higher tier unlocks more features and add-ons, or enables a larger scale. Higher-tier licenses typically provide access to additional features beyond the base software. For example, a database might offer a Standard edition that limits the number of cores or memory, and an Enterprise edition with no limits and additional features.

Modular licensing: Some software offers optional modules or plugins: you purchase a base license, then separately license add-on modules for additional functionality. These add-on modules often include extra features not available in the base version.

The license agreement explicitly delineates these features: “Feature X is only available if you have an Enterprise Edition license.” Technical measures often block features unless a proper license key is present.

Other Models

CPU/Core/Server Licensing: In enterprise software (databases, server apps), licenses are sometimes tied to hardware capacity: “per processor core” pricing. Oracle uses this: you count the CPU cores in your server and buy a license for each. This captures value for high-performance use.

Site or Enterprise License: A broad license that allows unlimited use within an organization for a high price. A university might get a campus-wide license for software to install in labs without counting each seat.

Trial Licenses: Time-limited (30-day trials) or feature-limited versions provided under a license that automatically expires or restricts capabilities until you purchase the full license. A trial period allows users to evaluate the software’s features for a limited time before buying a full license, and certain features may be restricted during this period.

The industry has seen a steady shift from device-based, perpetual models to user-based, subscription models. A 2024 industry survey found that over 80% of new software products were offered on a subscription basis.

Usage Restrictions and Technical Enforcement

Proprietary licenses rely on both legal terms and technical controls to enforce permitted usage and prevent unauthorized copying or piracy. These licenses impose restrictions on how the software can be used, copied, or modified, and they are enforced through both legal agreements and technical measures. Proprietary software is often tightly restricted in how users can use it and what changes they can make.

Installation Limits & Activation

Vendors use several mechanisms:

Product Keys/Serial Numbers: A unique key is required to activate the software. However, keys alone can be shared if not tied to activation.

Online Activation: This became common in the 2000s. Upon installation or first run, the software connects to the vendor’s server to validate your license. Windows and Office require online activation: the product key is sent to Microsoft’s servers, which lock it to your PC.

License Files: Some enterprise software issues a license file locked to a specific machine’s hostname or MAC address.

Hardware Fingerprinting: Tying the license to hardware details (CPU ID, motherboard).

Periodic License Checks: Even after initial activation, some software “phones home” periodically to ensure the license is still valid. Adobe Creative Cloud requires an internet check-in every 30-90 days.

These methods have considerably reduced casual piracy. According to BSA, global piracy rates were 37% worldwide, with North America at 16% and Western Europe at 26%.

Concurrent User Restrictions

For floating licenses, enforcement is via a license server. When a user launches the software, it requests a license token from the server. If one is available, the server grants it, and the app runs. If no free licenses are available, the app is denied.

Section 1201 of the DMCA prohibits circumventing DRM or activation mechanisms, thereby supporting software vendors‘ DRM and imposing legal penalties for circumvention.

Functional Restrictions by License

If you have a basic versus a premium license, software vendors often ship a single build that includes all features but locks certain features unless a valid license is present. The software reads your license key to determine which features to enable.

If the vendor patents certain features, they receive a double layer of protection. The license restricts use of the feature to those with the proper license, and separately, using that feature without authorization could be patent infringement.

Other Technical Protection Measures

Code Obfuscation: Making the compiled code difficult to reverse engineer. This helps prevent hackers from cracking the software or understanding proprietary algorithms.

Integrity Checks: Some software does self-checks to ensure it hasn’t been modified.

Online Verification of Authenticity: Some apps regularly verify licenses online to catch shared keys or pirated copies.

Usage Analytics: Some vendors use telemetry to detect suspicious usage (like identical license keys logging in from different countries simultaneously).

Geo-Blocking: If the license prohibits use in certain countries, the software may block access to those countries.

Proprietary software enforcement is a cat-and-mouse game, but as software moved to the cloud and activation became ubiquitous, piracy has been curtailed, especially in enterprise settings.

Intellectual Property Protection: Copyright, Trade Secrets, and Patents

A proprietary license is one pillar of software protection, but for SaaS founders seeking venture funding or building defensible competitive advantages, it’s not enough on its own. An effective software IP strategy leverages copyright, trade secret law, and patents. This layered approach is what transforms a good product into a fundable, valuable, defensible business. For SaaS founders and tech startups, understanding how these three IP layers work together is critical for protecting your competitive advantage and maximizing valuation.

Copyright Protection

Copyright automatically protects software code as a literary work from the moment it is written. The exclusive rights include reproducing, distributing, and creating derivative works from the code.

If someone copies substantial portions of your code without permission, they infringe your copyright. This applies to source code and object code, as confirmed by Apple v. Franklin.

No registration is needed to have the right, but registering in the U.S. gives added benefits: you need a registration to sue for infringement in federal court, and timely registration allows you to seek statutory damages and attorney fees. The U.S. Copyright Office receives about half a million registrations yearly, many of which are for software.

What copyright doesn’t protect well: Ideas, algorithms, functional aspects. It only protects the specific expression of code. Two programs can have identical functionality without copyright conflict if written differently.

Trade Secret Protection

A trade secret is information that derives value from not being generally known and that you take reasonable steps to keep secret. Software companies keep their source code as a trade secret.

To maintain trade secret status, companies must enforce confidentiality through employee/contractor NDAs, repository access controls, security measures to prevent leaks, and marking code as confidential.

In the US, the Defend Trade Secrets Act (2016) provides a federal cause of action for theft/misappropriation of trade secrets.

Limitation: Trade secrets don’t prevent independent rediscovery. Once a secret is out publicly, protection is lost.

Patent Protection

Patents can protect the novel functional ideas and implementations in software: things copyright can’t cover because copyright doesn’t cover functionality or methods. This is where software patents become critical for SaaS and tech startups.

A patent grants the owner the right to prevent others from making, using, or selling the invention defined in the patent claims, typically for 20 years from the filing date.

Examples of what can be patented:

- Algorithms (particularly ones with a technical effect).

- System architectures or protocols.

- Data processing techniques.

- User interface innovations.

A recent analysis showed that about 50% of European patent grants in 2023 were software-related, and in the US, almost 63% of utility patent applications in 2023 were for software innovations.

Why startups and companies file patents:

Exclusive Rights: If you have a novel approach, a patent can block competitors from using that approach, even if they reimplement it themselves.

Investment value: Startups with patents are more than 6× as likely to secure Series A funding as those without. For SaaS founders raising capital, a strong patent portfolio signals defensible IP and can significantly increase valuation.

Case example: Google patented PageRank early, giving it a period of exclusivity. RSA Security patented the RSA encryption algorithm in 1983 and licensed it widely until its patent expired in 2000 (EMC acquired it for $2.1B in 2006).

Post-Alice landscape: The 2014 Alice v. CLS Bank Supreme Court decision set stricter rules against patents on abstract ideas implemented on a computer. Since Alice, many software patents have been harder to get, but innovative technical solutions (primarily tied to hardware or that improve computer functionality) are still patentable. This makes working with experienced patent counsel who understand post-Alice strategies even more critical for software companies. Learn more about navigating Alice in our comprehensive guide to software patent strategies.

Integration with Licensing

Vendors often list patent numbers in EULAs or documentation to put users and competitors on notice. Some proprietary software EULAs have a clause: “Licensee is granted a non-exclusive license to use the Software. No patent rights are granted except to the extent necessary to use the Software as permitted.”

This clarifies that using the software doesn’t authorize them to use your patents outside that context. It prevents someone from asserting an implied license to a patent by purchasing the software.

If you have known patents covering the software, you can list them: “This Software is protected by one or more patents, including US Patent Nos. X,XXX,XXX.”

U.S. courts awarded about $4.67 billion in patent infringement damages in 2020, with approximately 60% of patent disputes settling out of court.

Combining Remedies

In an enforcement scenario, having multiple IP protections gives multiple legal avenues:

- If someone copies your code, file a copyright infringement lawsuit.

- If someone independently writes software that uses your unique methods and you hold a patent, file a patent infringement lawsuit.

- If an ex-employee stole your code or customer list, file a lawsuit for trade secret misappropriation.

All the while, your license agreements reinforce these through breach-of-contract claims.

Using all three (copyright, trade secrets, and patents) is standard in software companies’ IP strategy. A competitor would have to either completely innovate around all your patents and UI/design (costly and potentially inferior), try to license your IP (a potential revenue stream), or risk a lawsuit.

From an investment and M&A perspective, a startup with a solid patent portfolio and precise license controls can command a higher valuation. Tech acquirers often evaluate the target’s IP: owning patents can help fend off post-acquisition lawsuits or provide leverage in cross-licensing with large players.

For SaaS founders, integrating patent and licensing strategies from day one provides the strongest protection. Learn more about software patent strategies for SaaS companies in our comprehensive guide.

Proprietary License vs. Open-Source License

Understanding the fundamental differences between proprietary and open-source licenses helps every software stakeholder make informed decisions. The primary alternative to proprietary licensing is open-source licensing, which focuses on user freedom and transparency.

In the summary table or comparison, proprietary software offers several advantages, including dedicated support and enhanced security. However, proprietary software disadvantages include limited customization, higher costs, and dependency on vendor support.

When it comes to source code access, users of proprietary software cannot access it due to restrictions imposed by licensing terms and developer controls. In contrast, open-source software allows users to gain access to and modify the source code.

Open-source software is often developed and maintained by independent developers, who contribute to projects without formal corporate affiliation. Examples of proprietary software include Microsoft Office and Adobe Photoshop, while open-source software includes Linux and Mozilla Firefox.

Licensing models differ significantly: proprietary terms are used to protect proprietary rights through licenses, patents, and trade secrets. Some proprietary software may also include open-source components, but these are subject to proprietary terms.

Source Code Access

Proprietary: Source code is closed. Users receive only binaries and are not permitted to view or modify the underlying code. Due to licensing restrictions, users cannot access the source code, limiting their ability to adapt or modify the software.

Open-Source: Source code is open and accessible by definition. Licenses such as GPL, MIT, and Apache allow or require the source code to be provided.

Modification Rights

Proprietary: Users are generally prohibited from modifying the software. The EULA will state that no alterations or derivative works are permitted.

Open-Source: Typically allowed and encouraged. Most open-source licenses explicitly permit the creation of derivative works. Some licenses (copyleft ones like GPL) then require you to share your modifications under the same license if you distribute them.

Redistribution

Proprietary: Forbidden without permission. You cannot share the software with others.

Open-Source: Freely permitted with conditions. Open-source licenses allow you to redistribute the software (and often the source code) to others, subject to conditions such as retaining the original license and notices.

Cost

Proprietary: Usually involves license fees (or subscription fees). Proprietary commercial software is a product: you pay per license, per user, or by another metric.

Open-Source: Often free of charge for the software itself. However, companies may pay for support, hosting, managed services, or enterprise add-ons.

Support & Warranty

Proprietary: The vendor usually provides support (either you pay for it or it’s included). In practice, if you are a paying enterprise customer, the vendor typically has a support obligation defined in a support contract or SLA.

Open-Source: Typically, no official support is available unless provided by third parties or a sponsoring company. The license itself usually comes with no warranty. However, many open-source projects have community support, and companies can pay for support from providers. Red Hat sells Linux support; It was acquired by IBM for $34B in 2019.

Compliance Focus

Proprietary compliance: Focus on not exceeding usage rights and not violating restrictions. Audits and license checks police compliance.

Open-source compliance: You must comply with the open-source license terms. That usually means preserving notices, giving credit, and if it’s a copyleft license, providing source code for your modifications under the same license.

Monetization Approaches

Proprietary vendors monetize through direct license sales, subscriptions, and support contracts.

Open-source projects have alternative monetization:

- Dual Licensing: Software released under an open-source license, but the company also offers it under a commercial proprietary license.

- Open-Core: Core software is open source, but certain advanced features are proprietary.

- Software-as-a-Service: Give away the code but offer it as a hosted service for a fee.

- Support and Services: Give code away but sell training, consulting, and support SLAs.

Summary Table

| Aspect | Proprietary | Open-Source |

| Source code | Closed, inaccessible to users | Open, freely viewable by anyone |

| Modification | Prohibited | Typically allowed (often encouraged) |

| Redistribution | Forbidden without permission | Permitted (with conditions) |

| Cost to acquire | Usually requires a license/subscription | Usually free (but might pay for support) |

| Support | Vendor-provided support | Community or third-party support |

| Compliance focus | Usage limits/audits | Honor license terms (attribution, copyleft) |

| IP | Vendor retains patents, copyrights | Apache 2.0 includes a patent grant; the GPL has patent clauses |

The “proprietary vs. open-source” debate often centers on philosophy: proprietary advocates emphasize quality control, stable funding, and support accountability; open-source advocates emphasize freedom, innovation through collaboration, and avoiding monopolistic control.

In practice, modern IT environments use a mix of both. Even proprietary software frequently incorporates open-source components: in 2023, over 96% of codebases included at least one.

Patents in both worlds: Proprietary companies typically do not license patents to users except for limited use of the software. In open-source licenses, terms such as the Apache 2.0 license include a contributor’s patent grant and a patent retaliation clause. This is an essential protective measure for open-source.

Hybrid strategies: Many modern products combine open-source and proprietary licensing. For example, Databricks open-sourced a project (Delta Lake) but offers proprietary enhancements. Microsoft open-sources developer tools (VS Code, .NET runtime) but sells proprietary Azure services. Google’s Android OS is open-source (AOSP), but many features/apps are proprietary.

Examples of Software Distributed Under Proprietary Licenses

Real-world examples across various categories illustrate how proprietary licensing works in practice, and more importantly for SaaS founders, how different companies combine licensing with patents to create defensible competitive advantages. Notice how the most successful software companies don’t rely on licenses alone. Proprietary software companies and proprietary software vendors develop and distribute software programs under the proprietary software model, offering multiple advantages such as dedicated support, enhanced security, and user-friendly interfaces. However, proprietary software also has disadvantages, including limited customization, higher costs, and dependence on vendor support. Software developers play a crucial role, creating and maintaining proprietary software while ensuring compliance with licensing restrictions.

Desktop Operating Systems:

Popular examples of proprietary operating systems include Microsoft Windows and macOS. Microsoft Windows is one of the most widely used operating systems globally, developed and marketed by Microsoft as a proprietary solution. macOS is a proprietary operating system developed by Apple and is exclusively used on Apple’s Macintosh computers. These systems are protected by copyright and licensing agreements that restrict modification and distribution.

Productivity and Creative Software:

Adobe Photoshop is a well-known proprietary software used for image editing and graphic design, widely adopted by professionals and hobbyists alike. iTunes, a proprietary media player and media library application developed by Apple, is another popular example, allowing users to organize and play digital music and videos.

Enterprise and Database Software:

AutoCAD is a proprietary computer-aided design (CAD) software widely used in architecture and engineering for drafting and modeling. Oracle Database is a proprietary relational database management system known for its scalability and security. At the same time, Microsoft SQL Server is a proprietary relational database management system developed by Microsoft for enterprise data management.

Cybersecurity and Utility Software:

Norton Antivirus is proprietary antivirus software developed by NortonLifeLock that provides real-time threat detection and prevention against viruses and malware. This is a popular example of proprietary antivirus software, which is created and maintained by specialized vendors to ensure robust security.

These popular examples demonstrate how proprietary software companies and vendors leverage the proprietary software model to deliver specialized software programs. Engaging skilled software developers helps ensure these products remain secure, reliable, and feature-rich. At the same time, users benefit from these advantages but must also consider the disadvantages of proprietary software, including restricted access and limited customization.

Desktop Operating Systems

Microsoft Windows 10/11: Microsoft Windows is a proprietary operating system and one of the most widely used globally. Windows is classic proprietary software. The EULA for Windows restricts installation to one computer. It forbids modifying system files, reverse-engineering, or sharing the OS. Running Windows in virtual machines is subject to licensing limits. Windows’ dominance (about 70%+ of the desktop OS market) underscores the ubiquity of proprietary operating systems.

Apple macOS: macOS is a proprietary operating system developed by Apple and is exclusively used on Apple’s Macintosh computers. The macOS Software License Agreement explicitly states you may install and use macOS only on Apple-branded computers. Installing macOS on a generic PC (a “Hackintosh”) violates the license. In Apple v. Psystar (2009), Apple sued a company selling non-Apple computers running macOS.

Productivity and Creative Software

Microsoft Office / Microsoft 365: Historically, Office was sold via perpetual licenses. Microsoft now heavily pushes Microsoft 365, a subscription-based licensing model. Microsoft reported over 345 million paid Microsoft 365 seats globally in 2024.

Adobe Creative Cloud: Adobe moved fully to subscription licensing in 2013. Adobe saw piracy drop considerably after the launch of Creative Cloud. As of the end of 2023, Creative Cloud had over 33 million paid subscribers.

Enterprise and Database Software

Oracle Database: Oracle’s database software is known for its strict, complex licensing. They license by processor cores for server deployments or by named users. Oracle’s license gives it the right to audit customers’ usage. Oracle’s EULA includes restrictions like not publishing benchmarks without consent.

Microsoft SQL Server: Microsoft offers this database under a range of licenses, including per-core for servers and Server+CAL. They have editions: Express (free, limited), Standard, and Enterprise.

SAP ERP, Salesforce: These enterprise apps often license per “user”, with different user types at various prices.

Cybersecurity and Utility Software

Consumer antivirus suites (e.g., Norton 360, McAfee) are proprietary software developed by individual companies to protect users from online threats such as viruses and malware. For example, Norton Antivirus is a proprietary antivirus software developed by NortonLifeLock. These suites are usually sold as annual subscriptions, with the license often covering up to a set number of devices and prohibiting the use of the consumer version in business settings.

Mobile Apps and Ecosystems

Apps on mobile phones are under proprietary licenses. When you download an app from Apple’s App Store, it comes with either the standard Apple App Store EULA or a custom EULA. App Store terms forbid reverse engineering or redistributing apps.

Video games on consoles are proprietary software subject to very strict licensing. When you “buy” a game, you license it for personal entertainment use.

These examples demonstrate varying enforcement intensity. Some consumer software uses light honor systems. Major enterprise software relies on rigorous audits and contracts. Cloud services are enforced via account control and rate limiting.

One famous case: Autodesk v. Vernor (2010): a seller tried to resell used AutoCAD software on eBay; Autodesk’s license stated the software is licensed, not sold, and cannot be resold. The court sided with Autodesk, affirming the EULA’s terms.

Compliance, Audits, and Legal Consequences

Using proprietary software in an organization comes with a responsibility: license compliance. Failure to comply can lead to severe financial and legal repercussions. Failing to understand or comply with proprietary software license terms can result in significant legal issues, including monetary penalties and potential legal action.

The Audit Process

Major software vendors (Microsoft, Oracle, IBM, Adobe, SAP) and industry groups like the BSA conduct software license audits of business customers.

How an audit works:

Notice: Typically, 30 days’ notice. Some enterprise agreements specify how often (no more than once a year).

Data collection: The company being audited is asked to provide deployment data via vendor-supplied scripts or tools.

Scope: Audits can cover all software by that vendor or specific titles. BSA-led audits often ask for proof of licenses for a range of products.

Findings: Once data is gathered, they compile a compliance gap analysis and present findings along with remediation steps.

A 2020 survey indicated that about 35% of companies had been audited in the past year by at least one software vendor.

Common Violations Uncovered

Excess installations/users: The classic “too many copies.” A business buys 50 licenses but installs them on 60 machines.

Using higher-edition features without a license: Using Oracle Database Enterprise Edition options without a license can incur significant compliance fees.

Unauthorized key sharing: Buying one Adobe Creative Cloud account and sharing the login among multiple designers.

Circumventing activation: Using cracks or fake license servers. Using KMS emulators for Windows/Office is outright piracy.

Misuse of license type: Using educational licenses or student editions for commercial business.

Case example: In 2019, Sprint paid $5.5 million to settle a BSA claim of unlicensed software use. Wyndham Hotels paid $150k in a BSA settlement for unlicensed copies of Microsoft Office and Symantec software.

The BSA collected $2.4 million in fines from 20 U.S. companies in one campaign. BSA even runs an informant reward program offering up to $200K.

Consequences of Non-Compliance

Back Licensing Fees: The vendor will require you to purchase licenses for all unlicensed uses, often including past usage.

Penalties: Some agreements allow charging interest or penalties. BSA often seeks additional damages beyond the purchase of the software.

Legal Action: For copyright infringement, they could seek statutory damages of up to $150K per work infringed willfully. Adobe v. Forever 21 (2017): Adobe sued the retailer for using cracked Photoshop; they settled.

Injunctions: A court can order the company to stop using the unlicensed software.

Reputational Damage: Getting named in a BSA press release is embarrassing for companies.

Security risk: 33% malware risk with unlicensed software, $2.4M avg cost per incident, 50 days resolution.

Prevention

Many organizations implement Software Asset Management (SAM) programs. The ISO/IEC 19770 standard provides a framework for SAM. The BSA claims companies can save 30% on software costs with proper license management. The U.S. MEGABYTE Act of 2016 requires federal agencies to implement SAM.

Strategies for Vendors: Designing Strong Proprietary Licensing

If you’re a software vendor or SaaS founder, how do you structure your licensing and IP strategy to maximize revenue, protect your product, and build investor-attractive defensibility? The answer lies in integrating licensing with comprehensive IP protection from day one.

1. Match Revenue Model to License Structure

Choose a licensing model that aligns with how your product delivers value and how customers expect to pay. Consider perpetual if customers prefer CapEx; subscription for recurring revenue (investor preference); named user for company-wide B2B; floating for occasional use; CPU/core for server software; or feature-tiered for value differentiation.

80%+ of new software products offered subscription in 2024, reflecting the industry shift.

2. Protect Core Innovations with Patents

Identify core technical differentiators and file patents early. Ideally, file before public release (the US allows a 12-month grace period after disclosure; most countries require filing before any disclosure).

Consult a patent attorney who understands software and recent case law. File provisional patents to get a priority date quickly if you’re an early-stage company. Target patents that could block competitors from achieving the same result via similar paths.

In 2023, almost 63% of U.S. utility patent applications were software-related. Startups with patents are 6× more likely to get funding.

Google’s PageRank patent gave them exclusivity in the formative years. RSA Security’s patent generated significant licensing revenue until expiration (EMC acquired the company for $2.1B in 2006).

For SaaS founders, understanding which features are patentable and how to structure claims that withstand post-Alice scrutiny is critical for fundraising and competitive protection. Schedule a free IP strategy call to evaluate your software’s patentability and develop a comprehensive protection plan, or download our SaaS Patent Guide 2.0 to identify which of your features qualify for patent protection.

3. Integrate Patents into License Terms

Include EULA clauses: “Licensee receives no patent rights except to use the Software as permitted.” List patent numbers in documentation. Include patent restrictions on third-party components. Consider termination clauses for patent challenges in partner agreements.

4. Protect Trade Secrets

Keep source code tightly controlled with access control, NDAs with employees/contractors, mark code as confidential, include EULA confidentiality clauses, secure cloud dev tools, and document your trade secret list.

Uber vs Waymo (2017) resulted in $245 million settlement for trade secret theft, demonstrating the importance of these protections.

Consider obfuscation and anti-reverse engineering techniques for distributed software.

5. Design Measurable License Metrics

Define users, devices, cores, and instances clearly. Provide self-monitoring tools and usage dashboards; embed enforcement mechanisms: activation keys, periodic checks, feature toggles, and license servers for concurrent use.

Balance DRM with usability to avoid alienating legitimate customers.

6. Provide Support and Documentation

Value-add through support, training, and precise documentation for paying customers. Provide license summaries and FAQs addressing common concerns.

7. Align Legal Strategy with Business Growth

Periodically review the company’s licensing and IP strategy as it grows. Monitor competitor actions. Use patents defensively to secure cross-license agreements with large players. During valuation events (fundraising, M&A), showcase clean IP ownership and patent portfolio.

Strategies for Users and Organizations

If you’re an organization using multiple software applications, proactively manage proprietary licenses to stay compliant and control costs.

1. Maintain a Centralized Inventory

Track all software in a SAM system: products, versions, quantities, entitlements, purchase records, expiry dates, license terms, and user/device assignments. Use tools such as Flexera or Snow for automated inventory and compliance checks.

With this central view, you can respond to audits instantly, identify unused licenses, detect unauthorized installations, and manage renewals.

2. Review Agreements Before Deployment

Have procurement or legal review EULAs for unusual restrictions. Look for audit clauses, data/privacy terms, virtualization restrictions, geographic limits, end-of-life provisions, open-source components, and indemnification/liability terms.

Negotiate problematic terms: Remove benchmark prohibitions, add transfer rights for mergers, get dev/test licenses, clarify DR handling, and limit audit frequency.

3. Implement Technical Controls

Use application whitelisting, software distribution tools (IT-only installation), license servers for floating licenses, network controls (CASB for shadow IT), VM cloning alerts, and SSO integration for SaaS.

4. Train Employees

Educate staff on policies: no unapproved software; no credential/key sharing; request tools through IT; and the consequences of violations. Highlight the security angle: torrented cracks pose a malware risk.

5. Conduct Internal Audits

Self-audit at least annually. Compare inventory versus purchase records. Budget for growth. Focus on high-risk software (Oracle, Autodesk, Microsoft, Adobe). Document self-audits to demonstrate good faith. Retain proof of licenses.

6. Negotiate Favorable Terms

For large purchases, negotiate: include dev/test licenses, disaster recovery rights (cold standby at no cost), audit notice/procedure (60 days, once per 2 years, 5% tolerance), transfer rights, future tech clauses, price lock on true-ups, source code escrow, sublicensing provisions.

7. Consider Open Source Alternatives

Evaluate if open-source solutions (PostgreSQL vs Oracle, Linux vs Windows) could replace proprietary software. Use as leverage in vendor negotiations. Balance TCO, including support and expertise needs.

Avoiding vendor lock-in is important: proprietary vendors often raise fees or unilaterally change licensing terms. Having alternative plans or a diversified software stack mitigates risk.

FAQ

Question 1: Can a company patent its software if it already distributes it under a proprietary license?

Yes. Having software in the market doesn’t prevent patenting underlying inventions if filed within the allowed timeframes. A software license (EULA) and a patent are separate: a license is a contract with users, a patent is a government-granted right.

Ideally, file before publicly disclosing. In the U.S., there’s a 12-month grace period after the first public disclosure. Other countries often have zero grace period. If software is publicly available for more than a year, in most jurisdictions, you can no longer obtain a patent on those aspects.

Patenting requires disclosing the invention, trading secrecy for protection. But proprietary licensing and patenting complement each other: a license enforces usage terms, a patent stops competitors from implementing the same functionality.

Many successful software companies do both: Oracle holds patents on database technology while licensing software; Adobe patents image-processing techniques. If a competitor tried to clone features, Adobe could sue for patent infringement even if no code was copied.

Consult a patent attorney early. Once patents are filed, label the product with “Patent Pending” or patent numbers to deter copycats.

The key is filing strategically and early. Schedule a free IP strategy call to determine the optimal timing for patent filing relative to your licensing strategy and market launch.

Question 2: Do I own the software I buy under a proprietary license?

No. You own the license (the right to use under specified conditions), not the software. Buying proprietary software is not like buying a physical object. The vendor retains ownership of code, design, and all IP.

When you purchase Microsoft Office, you don’t own Word or Excel: Microsoft does. You have a license to run Office under defined conditions. You can’t resell copies, publish code, or claim it as your product.

You may own physical media (DVDs) or the device on which it’s installed, but the software content is licensed. This is why the “first sale doctrine” does not apply neatly.

Courts often uphold EULAs. Autodesk v. Vernor (2010): The court held that Autodesk’s license precluded resale because it was a license transaction, not an ownership transfer.

Exception: EU’s UsedSoft v. Oracle (2012) ruled perpetual licenses can be resold under certain conditions.

Think of it this way: proprietary software is protected by copyright. Under copyright law, the default is that you cannot copy or use without permission. The license is that permission.

Question 3: Can I modify proprietary software for internal use if I never distribute it?

Typically, no, not without violating the license. Most proprietary EULAs have a blanket prohibition on reverse engineering, decompiling, and modifying software. This holds even if you don’t plan to distribute modified software.

If you hex-edit the binary to change a feature, that’s a modification; the EULA likely forbids it. Even adding to the software can be an issue.

Exceptions:

To learn more about how SaaS businesses can protect unique software features from competitors, see these strategies to stop competitors from stealing software features.

- Some enterprise agreements or open APIs allow limited customization through documented APIs (VBA macros in Excel = using a feature, not a breach).

- The EU Software Directive allows reverse engineering for interoperability (narrow scope).

- Source code escrow/licensing (rare, high-cost specialized software).

But as a rule, modifying proprietary executables is prohibited under the EULA and can infringe copyright (by creating a derivative work). Even if you never give a modified version to anyone, you’ve created an unauthorized derivative.

Vendors typically offer customization through settings or official APIs, not direct alteration. If you genuinely need to modify it, you’d need the vendor’s written permission or a source code license.

This is one motivation for open-source: with the source code, you can modify it to your needs. With proprietary, you trade that freedom for the vendor’s support and integrated features.

Question 4: Is it possible to combine proprietary and open-source code in one product?

Yes, but requires careful license compatibility analysis and often architectural separation. Many companies successfully incorporate open-source components within proprietary products.

Permissive licenses (MIT, BSD, Apache 2.0): Usually compatible with proprietary use. You can include MIT-licensed code in your product; you typically just need attribution. Apache 2.0 explicitly allows proprietary distribution with license text and notice.

Weak Copyleft (LGPL, MPL): Allow combining with proprietary code under conditions. LGPL permits linking proprietary code to an LGPL library if the library can be replaced at runtime (dynamic linking). MPL allows mixing if MPL-covered files remain open and separate.

Strong Copyleft (GPL, AGPL): Tricky. GPL requires the entire program to be released under GPL if a derivative work is distributed. Most proprietary software avoids GPL code or uses it in separate processes. AGPL is stricter: even network use triggers source sharing.

Best practice: Stick to permissive/LGPL for included OSS. Isolate the GPL if necessary. Legal counsel should review. This is critical due diligence: improper use of the GPL risks enforcement action that could require you to open source.

Projects like OSSRA show that 96% of codebases are open source. Key is compliance: Honor attributions (the Open Source Components section in the documentation). If the license states “share modifications,” either share or design, but not both, so you didn’t modify.

Example: Apple’s macOS uses open-source components (Darwin core, BSD/GPL tools). Apple complies by releasing the source code for those components, but keeps its proprietary GUI/frameworks closed. They architected separation between open and proprietary parts.

Getting this right requires experienced legal counsel who understands both open-source compliance and proprietary software protection. Contact our team for guidance on safely integrating open-source components while maintaining strong IP protection.

Question 5: What happens to my license if the vendor stops supporting the software?

Depends on license type and terms:

Perpetual license: You can typically continue using software indefinitely, even if the vendor goes out of business. Example: Adobe Creative Suite 6 purchased in 2012 can still be used today. Risk: As systems evolve, old software becomes incompatible or insecure. If the software checks in for activation and the server shuts down, you may have trouble. Some vendors release patches to remove activation requirements.

Subscription/SaaS: You typically lose access entirely once service ends. Most SaaS contracts state that if they terminate service, your rights end (possibly after the data retrieval period). A license doesn’t guarantee service availability beyond the contract terms.

Maintenance contracts on perpetual licenses: You still have the latest version under perpetual license, but won’t receive further updates. This raises security issues over time.

Escrow clause: Some licenses (especially enterprise) place source code in escrow. If the vendor goes out of business or stops supporting, the code is released to licensees so they can maintain it themselves. Common in high-stakes software, such as banking systems.

Many EULAs disclaim obligation to support beyond terms. So, legally, there is no guarantee of ongoing access in SaaS or of ongoing patches in perpetual licensing beyond the initial warranty.

Due diligence is essential: assess vendor stability. Have an exit strategy: ensure you can obtain a perpetual license for the latest version if the subscription service ends, or have data migration plans in place.

This vendor lock-in risk drives some organizations toward solutions that prevent being locked out if the vendor disappears, or toward open-source for longevity. With open source, even if the original maintainers drop it, the source code remains available, allowing others to continue development (OpenOffice forked into LibreOffice when Oracle dropped support). Organizations considering open-source or proprietary solutions should consult with an intellectual property attorney to ensure their legal rights and long-term interests are protected.

Summary:

- Perpetual: The license continues (you can still use it), but you face increasing risks over time; eventually, you may need to replace it.

- Subscription: Likely to lose software entirely after the period; plan to transition to another solution.

- Always secure your data and critical IP in the event you need to move.

Your Next Steps to Software IP Protection Success

Understanding proprietary software licensing is just the beginning. For software companies and SaaS founders, the real competitive advantage comes from integrating licensing strategy with comprehensive IP protection: patents that cover your core innovations, trade secrets that protect your source code, and copyrights that defend your expression.

The bottom line: weak IP protection leaves your software vulnerable to competitors who can reverse-engineer your features, copy your innovations, and undercut your market position. Weak patents don’t just fail to protect; they actively help competitors by creating roadmaps to design around your IP. Strong IP protection, combining strategic patents with well-structured licenses and trade secret protection, creates legal barriers that deter copycats and give you enforcement options when competitors cross the line.

Without a proper IP strategy, you risk losing control of the innovations that drive your business. Competitors can study your product, replicate its features, and capture market share, leaving you with limited legal recourse. For SaaS companies, especially, where algorithms and system architectures create competitive differentiation, the stakes are even higher: investors specifically look for defensible IP when evaluating funding opportunities.

Take these immediate actions:

- Schedule a Free IP Strategy Call with our patent team to evaluate your software’s patentability, review your current licensing structure, and develop a comprehensive three-layer protection plan that integrates patents, licensing, and trade secrets for maximum defensibility and investor appeal.

- Download our SaaS Patent Guide 2.0 to understand which features in your software are patentable and how to structure claims that withstand post-Alice scrutiny.

- Review your current license agreements to ensure they explicitly reserve patent rights and don’t inadvertently grant implied licenses to your IP.

- Audit your trade secret protections to verify that you have appropriate NDAs, access controls, and confidentiality clauses that protect your source code.

Strong IP protection isn’t just about defense: it’s about creating business value. Whether you’re raising capital, negotiating partnerships, or preparing for acquisition, a comprehensive IP strategy that combines patents with smart licensing dramatically increases your valuation and negotiating power. The investment you make now in robust IP protection pays dividends throughout your company’s growth.

Andrew Rapacke is Managing Partner at Rapacke Law Group and a Registered Patent Attorney specializing in software patents, SaaS IP strategy, and tech startup legal needs. With extensive experience helping tech founders protect innovations and raise capital, Andrew and the RLG team provide fixed-fee patent services with transparent pricing and guaranteed results.

Connect with Andrew on LinkedIn or follow @rapackelaw on Twitter/X and @rapackelaw on Instagram for regular IP strategy insights.

To Your Success,

Andrew Rapacke, Managing Partner

Rapacke Law Group